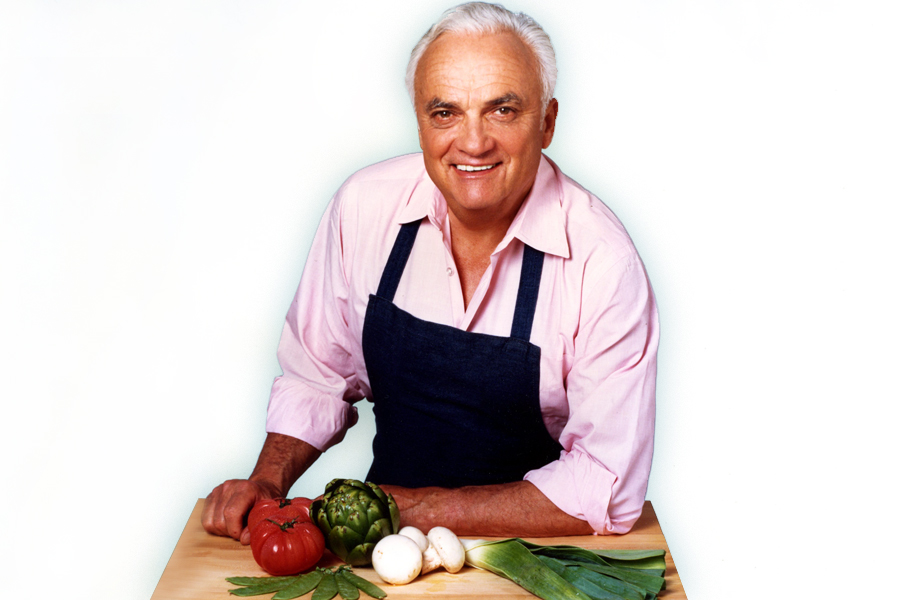

Beloved Hamptons Chef Pierre Franey, and His Recipes, Live On

“Papa—he cooked to live, he lived to cook.”

The internationally acclaimed “60-minute Gourmet” syndicated columnist, Chef Pierre Franey, who would have been 93 this month, was unique. He was also beloved, especially in Springs, where he lived and worked for more than 40 years, chatting up neighbors whom he’d meet at the local marina or around town, inviting them to write or call him (he loved to teach). He was a man who, while passionate about cooking, was also incredibly down-to-earth about his fame.

Now, thanks to a new website created by his children—Diane (59), Claudia (61) and Jacques (51)—Pierre Franey will continue to delight and instruct, while attracting a new generation of fans, particularly younger folks more likely to look for recipes online than in print. The site, pierrefraney.com, launched last May and has quickly hit a hot spot with food and wine lovers. “He taught me how to cook,” gushes one foodie.

For Diane, Claudia and Jacques, the website keeps their father’s work current by slightly modifying French recipes that were heavy on sweets and carbs. (The “low calorie” steak and mustard sauce Recipe of The Month, proved rich and incredibly delicious.)

A classically trained French chef “in the old ways,” Franey was born in a small Burgundy village and nicknamed Pierre Le Gourmand, as he demonstrated an early love of food and cooking. As a child he would feast on rabbits marinated in red wine and snails in garlic as he prepared family meals on a wood-and-coal stove. When he was 13, his parents sent him to Paris, where he began culinary training, working his way up from apprentice at a Paris brasserie (six days, insane tasks and hours, no money) to become a master chef in all areas.

In New York, Franey headed the kitchens at Le Pavilion, La Cote Basque and, later, The Hedges in East Hampton, though he never let professional life eclipse family life on Gerard Drive, with his wife Betty. Betty Franey was a cultural force of her own on the East End—she was a founding member of what was to become the Accabonac Protection Committee, and during her 50 years in Springs she also served as President of the Springs Improvement Society and as a trustee of East Hampton Town and the Nature Conservancy.

Cooking was always a heartfelt affair in the Franey household. Diane points with pride to the original five-star range her father was given when he started his “Kitchen Equipment” column for The New York Times, his second column with the paper. Franey’s first stint with the Times was the popular “60 Minute Gourmet,” which he wrote with Craig Claiborne.

Franey was also a familiar and adored presence every August at the Fisherman’s Fair in Springs, where he and Claiborne would serve up some mean clam chowder, crêpes and moules marinères. It’s unlikely that many who strolled the grounds realized they were being served by a famous print and television personality, and even less likely that those who did recognize him knew the French chef was such an American patriot and humane person. He was chosen to cook at the French Pavilion at the 1939 World’s Fair, his ticket to the U.S. When WWII broke out, Franey joined the U.S. Army, and he was summoned by General Douglas MacArthur to be his personal chef at the Pentagon. He rejected the prestigious offer, eventually joining the infantry and winning a Purple Heart as sergeant.

After WWII ended, Franey returned to Le Pavillon in Manhattan, becoming executive chef in 1952. In 1960 he famously got into a bitter dispute with Le Pavillon’s Henri Soulé over wages and hours for the staff, prompting a massive walk-out. He also worked for a while for Howard Johnson, Sr., meeting his challenge to cook well for the masses.His children have struck out on their own: Diane, a visiting nurse with the Dominican Sisters, specializes in working with patients suffering from diabetes or wounds. Claudia, who went into early childhood education, wrote Cooking With Friends with her father. Jacques, who worked in the kitchens in France, decided to go into wine. He now manages Domaine Franey Wines & Spirits in East Hampton.

As Diane says, Papa was not initially encouraging of his daughters going into the food or restaurant business, seeing it as too hard and demanding for them. However, he did come to see that the times—and women—were changing. She adds that Franey was prescient in seeing that many French chefs “stayed in the rut,” continuing to turn out food in the old French classical tradition without acknowledging other cultures. In this regard, she says, Claiborne was influential, introducing Franey particularly to Asian, Italian and Southern cuisine. Diane points out that her father was also one of the first to respond to interest in nutritious food in an age of growing health concerns. But, he never yielded to the lure of the exotic.

In fact, he was critical of precious markets with their esoteric ingredients. Fish, for example, was best if locally caught and simply prepared. No need to subscribe to getting ingredients “direct from the Himalayas.” He had his own Eden outside his family compound off Gerard Drive, where he grew herbs and vegetables. And he may well have been the first on the scene, Jacques adds, to introduce fingerling potatoes, which he started with seven plants.

Many people came to know Pierre Franey from his TV shows. “That was him,” says Diane. “No acting,” except for his sign-off, which he never got right because, well, it was the only scripted part of the show. In order to ensure that viewers felt the authenticity of the program, he would bring in props from his own house. He wanted the show “to seem like home.” Even his dog Luc would make appearances.

He delighted in the modern. A food processor replaced the laborious food mill. Claiborne, who would hover around with his typewriter, took down everything Franey was doing in the kitchen. The two would then work out how to present the recipes to their audiences. They worked well together, calling to mull over this and that, experimenting.

Pierre Franey suffered a fatal stroke in 1996, just after conducting a cooking demo for 400 people on the Queen Elizabeth II. Franey later died at a hospital in Southampton, England. He is buried, as is many an artist, in Green River Cemetery in East Hampton, with herbs maintained at his gravesite. The legacy goes on, however, even if it skips a generation: Diane’s daughter Noelle works as a private chef on the East End. And all three of Pierre Franey’s children have accomplished their “2013 mission”—to establish a website in his name. They sustain and enhance their father’s reputation by way of links to his books, videos, recipes and a picture gallery—not to mention an opportunity for viewers to subscribe to a newsletter featuring the Recipe of the Month. Bon Appetit.