Getting Free: Why Sag Harbor Should Erect a Statue to Christopher Vail

As we celebrate the signing of our Declaration of Independence this holiday weekend, it is important to recall the various skirmishes and battles that took place here in the Hamptons during that turbulent time. Men died to give us our freedom. And though the Hamptons and the rest of the East End remained in British hands until the very end of the war, it did not come easy for them to control the island.

Quite remarkably, there was one young man from Sag Harbor who figures quite prominently in many of these skirmishes and battles in the Hamptons. His name was Christopher Vail, and in 1775, when the Battle of Bunker Hill took place in Boston with the shot heard round the world, he was a 17 year old, working as a rope maker in that port town. The war had started. And he stepped forward. We know this because for the next five years he kept a diary of his life. A copy of it is in the Library of Congress in Washington. You can read it in its entirety if you like. You will find it, all 18,000 words of it, online at www.americanrevolution.org/vail.html. [expand]

Here is his very first entry. This was just two months after the Battle of Bunker Hill.

“I, Christopher Vail of Sagg–harbour, Suffolk County and State of New York enlist as a soldier in Capt. John Hulbert’s Company.”

He had joined the Rebels.

John Hulbert’s Company, known as the Bridgehampton Militia, assembled, trained and learned how to use their weapons on what was then a parade ground on the southwest corner of Montauk Highway and Ocean Road, right in the center of downtown Bridgehampton. There is a small park called Militia Park that sits behind Almond Restaurant on that corner today that marks the location. Across the street, on the northwest corner of the intersection, there exists today a historic marker, which notes that during Revolutionary War times, Wick’s Tavern existed on that spot. Men of all ages assembled here and argued back and forth about the rebellion that had now started.

At the time, the commerce on the East End consisted of cattle raising, farming and fishing. Many people supported the status quo. The British had mostly ruled the East End gently until that time. They had constables in Southampton and East Hampton. And everyone, after all, was a British subject.

If you want to fight, then go, the elders said. And so the young men, Christopher Vail among them, did. The company, consisting of several hundred men, boarded ships at Sag Harbor and headed to New York to receive further instructions from the newly appointed leader of the American Army, General Washington. Washington had them march to Ticonderoga to join a rebel force that was poised to capture the fort there. Off they went.

The Bridgehampton Militia arrived after Fort Ticonderoga had fallen. But the Commander there, happy to see them, ordered them to escort the British prisoners down the Hudson, the foot soldiers to a prison in Westchester, the officers to Philadelphia. The job took the better part of a month. And afterwards, in January of 1776, six months before the Declaration of Independence, Christopher Vail’s term with the Militia came to an end and he returned to Sag Harbor.

But he didn’t stay.

“I enlisted again in a few weeks as a private in Captain John Davis’ company, (with) Wm. Havens 1st Lieutenant in the continental service for 12 months, and was stationed at Montaug Point in order to guard a large quantity of cattle which was kept there, belonging to several towns.”

It had been reported by that time that King George III was sending 35,000 troops aboard many warships of the British Navy to Long Island and New York to put down the rebellion. It was believed if they landed on Long Island, they would be out of foodstuffs and they would be taking the people’s cattle. There were over 2,000 head at Montauk. So the locals allowed a contingent of rebels to go out there to protect them.

The British fleet did come by Long Island but it did not stop. It continued on, ultimately unloading 35,000 highly trained troops on Staten Island where, it was said, accurately, that the locals were inclined toward the crown.

The battle of Long Island took place on the Hempstead Plain on August 27, 1776, just 45 days after the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

A lot of preparation went into what both sides felt would be a key battle. General Washington assembled about 10,000 rebels near Brooklyn Heights, among them, on their south flank, John Davis’ Company as part of the Suffolk Militia. Meanwhile, the British brought over nearly 25,000 highly trained redcoats from Staten Island. There were also 5,000 Hessians —professional hired soldiers from Germany —and about 2,000 loyalists, who wore special green uniforms.

Christopher Vail was not among those about to fight, however. He and a small contingent of soldiers were still at Montauk, guarding the livestock. Two days before the battle was expected to start, however, the word went out that they should all head to Brooklyn to reinforce the Suffolk Militia. They started out. But on August 27, Christopher Vail wrote this in his diary:

“After marching 40 miles distance [from Montauk], we were informed that the Island was captured after a hard battle was fought, and a great loss on our side. We immediately began our retreat to Southold where we obtained vessels and carried our company over the Sound [to Connecticut.]”

George Washington’s rebel force had been thoroughly beaten in Brooklyn, not only by superior numbers, but also by superior weaponry, training and strategy. Men died on the field at close quarters, either shot by musket balls or run through with bayonets. In the end, about 300 patriots died, 600 were wounded and 1,100 were captured and taken to one of three British prison ships anchored in the East River where they were essentially left to die. (Vail would be imprisoned on one of these ships five years later for two months.)

After that day’s battle, General Washington, at night in a fog, was able to evacuate nearly 4,000 of his defeated men off Brooklyn and onto Manhattan to later retreat to Valley Forge.

As for the Suffolk Militia, stationed on the southern flank, they were surrounded and then when it was apparent that all was lost, surrendered to the Hessian Colonel Heinrich von Heerington, who later gave this account, true or false.

“The captured flag, which is made of red damask, with the motto ‘Liberty’ appeared with 60 men before [Col. Johann] Rall’s regiment. They had all shouldered their guns upside down, and had their hats under their arms. They fell on their knees and begged piteously for their lives.”

The southern coast of Connecticut, where Vail went after this battle, was filled with rebels, mostly young men sent away from eastern Long Island by their elders now that the Island was securely in British hands.

There were three major raids made by the rebels, crossing Long Island Sound in whaleboats to attack the British forts and ships on Eastern Long Island during the next two years. One was at Canoe Place in Southampton (and also in Speonk), another was in Setauket and the third, the one which is the most famous battle ever to take place in the Revolutionary War on eastern Long Island was in Christopher Vail’s hometown of Sag Harbor.

Astonishingly, Christopher Vail was part of every one of these raids.

In the Setauket raid, Vail described how they had burned the British Fort there and made off with several sloops and packet ships to New Haven. Here is how he describes the other raid, at Canoe Place (where the Shinnecock Canal is today).

“…The next day, went with our boats across the Sound, and landed at the Canoe place on L. Island and hauled the boats up in the bushes and marched up the Island about 20 miles to a place called Speonk where we took possession of 8 or 10 whale boats, and brought them off to New London.”

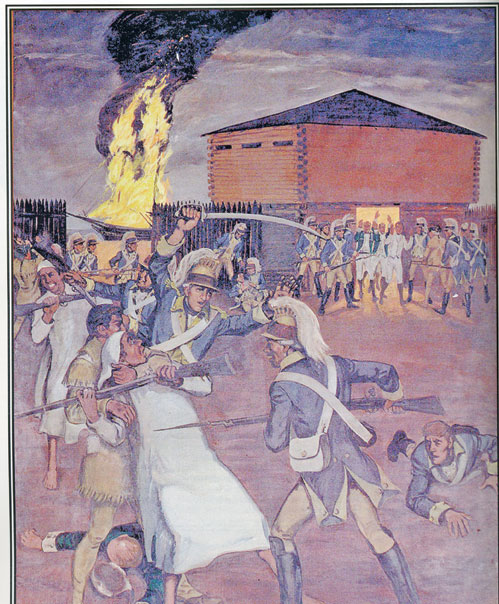

The raid on Sag Harbor took place on the night of May 23, 1777. Planned and led by Lt. Colonel Return Jonathan Meigs, the rebels left Connecticut in a virtual armada of whaleboats, 13 in all, carrying 234 men, one of whom was Christopher Vail.

Reaching the North Fork at what is now Truman Beach at about 1 a.m., the rebels carried their whaleboats up the beach, across the sand and the 100 or so yards of the peninsula to the wetlands on the south which was Peconic Bay. Here in the dark they relaunched their boats, crossed the Bay to Long Beach, Sag Harbor where without a sound they hauled up their boats onto the sand once again. From here they took off on foot for the British camp at the Old Burying Ground. But let Christopher Vail tell it.

“We proceed down to their quarters where we completely succeeded in capturing the whole force except one man. We burnt all the coasting vessels, which were all loaded and laid alongside the wharf, and a store that was 60 feet long that stood on the wharf.

“The British soldiers had just gotten their pay and many had been eating and drinking heavily.

They remained, went drinking etc., and all got pretty well boozy. When we arrived we took 99 Tories. Some had nothing but his shirt on, some a pair of trowsers, others perhaps 1 stocking and one shoe and in fact they were carried off in their situation to New Haven.”

In the encounter, no one was killed but the fire and explosion wiped out the whole British encampment.

After this raid, Christopher Vail joined the rebel navy and went off to sea. His purpose in doing so was to assist the ragtag fleet in the disruption and capture of British sailing ships trying to bring soldiers and supplies to their forces in America. He participated in some successes, but then on one outing fell into British hands where he was imprisoned, for a time, on the British-controlled island of Antigua. Escaping from there, he was caught again and imprisoned in London. All these accounts appeared in his diary. In London, inexplicably, he escaped but was also able to sign on as a seaman aboard a British privateer called “The Amazon,” which soon docked along the Portuguese Coast. Here, Vail jumped ship, and with a little help from the French made his way back to New London, Connecticut in June of 1791 where, amazingly, he just missed being involved in the most dramatic naval event of the war in the Hamptons—the sinking of the British Man o’ War Culloden.

In the interval when Vail was away, the battle for Independence swayed this way and that, with Washington taking Trenton and Princeton, then the British having more successes now in Virginia.

During this time, General Washington came to rely heavily on the information provided to him by a Long Island spy network, which used coded messages, special couriers and other means of subterfuge. (Patrick Henry, caught by the British and hanged, was one.)

In early 1781, the French—sworn enemies of the British—launched a special fleet of warships to America to help end the blockade the British were enforcing on the rebels. General Washington received information about this fleet from one of these spies, and he was also told, alarmingly, that the British already knew about this and now an even bigger contingent of British ships in New York Harbor were already heading out to meet the French in Long Island Sound to defeat them before they could even arrive.

Washington arranged for a trusted courier to deliver to the British in New York the misinformation that the French fleet was, in fact, now heading south toward Virginia and they should turn back.

The British in New York got this message, believed it, and did order the fleet back. However, two Man o’ Wars kept going. They were the H.M.S. Bedford and the H.M.S. Culloden, which carried 74 guns.

At this point, on January 23, 1781, the French fleet was safely in New London harbor and there was a storm coming up, which the two British man o’ wars ran right into. The Bedford came through the storm and returned to New York. But the H.M.S. Culloden went out of control and that night shipwrecked on the beach at what is now known as Culloden Point in Montauk, just a few hundred yards to the west of the entrance to Montauk Harbor.

All 650 crewmembers got off the ship safely after it came up the sand. Fearful that many of their cannons might fall into rebel hands, they took off whatever they could carry, burnt the Culloden down to the waterline, and then made their way back to New York City.

Christopher Vail, according to his diary, arrived aboard a French ship the rebel-controlled harbor of New London, Connecticut on May 6, 1781.

He had missed the final Revolutionary War event that took place on Long Island by just 100 days.

Amazingly, after just a week in New London, Vail went BACK out to sea to harass British ships. Serving as a crewman on the warship Jay, he assisted in catching and towing back to New London nine vessels, including two British privateers. Then, while the Jay was being refitted, he went out again to harass the British, this time aboard the warship Dean. And this time he was captured again.

Christopher Vail recorded the surrender of the British General Cornwallis, ending the war, while sitting in the squalid hold of the British prison ship Jersey in the East River along with about 10,000 other poor unfortunates. Here is his diary entry, that evening, after the guards left their posts and the prisoners took over.

“We heard the firing of cannon from the Jersey for rejoicing and whenever our people fired the British would fire from their batteries so as to confuse that people should not be informed of Cornwallis’s capture.”

With the war over, Christopher Vail made his way to Norwich, Connecticut, went into business, got married, bought a house in that town and raised a family. He lived to be 88 years old.

The HMS Culloden is still at Culloden Point in Montauk, underwater, and a protected federal park. You may scuba dive or skin dive down to it if you want though. [/expand]