Warning the British

One of the big items in the news last week was Sarah Palin describing Paul Revere’s ride to a bunch of citizens in Boston listening to her speak. She said that Paul Revere was off on horseback to warn the British that the rebels were not going to let them take away their arms. She also said that Revere rang bells and fired shots as he went to warn them.

That Palin said these things made her a laughing stock among many who heard about it. She’d had it backwards, they said. And it was not bells, it was lanterns.

Here is exactly what Palin said, as recorded at the meeting.

“He warned the British that they weren’t gonna be takin’ away our arms, by ringing those bells, and um, makin’ sure as he’s riding his horse through town to send those warning shots and bells that we were going to be sure, and we were going to be free, and we were going to be armed.” [expand]

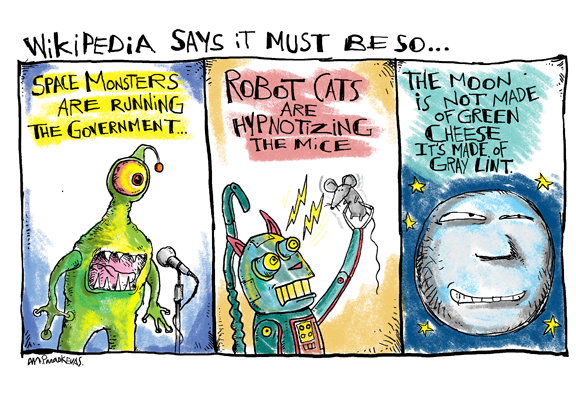

For days after she made this statement, people began writing posts on Wikipedia to slowly polish and create a four-paragraph explanation about what she said and what the facts were. Everyone is welcome to write posts. That’s why Wikipedia is the people’s encyclopedia. But unless the posts can be backed up by facts with footnotes attributing the sources, they get taken down. In the end, more than 20,000 people made posts of one kind or another. And about 19,800 of them were taken down because the attributions were either lacking or wrong. For example, one Palin supporter put up a post that said indeed Revere did ring bells and fire shots rather than shout “The British are coming.” His attribution was Palin herself and what she said at the meeting. Down it came.

No one at Wikipedia can recall a time, ever, when such enormous activity was swarming over a single question on that website.

The reasons were not only because it was difficult to understand Palin in some parts of her comment. There was also the matter of the ride itself, which is largely known today because of a patriotic poem written by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow 40 years after Revere died.

In Longfellow’s poem, Revere sees the British ships coming into Boston Harbor, and at midnight sees the two lanterns in the Old North Church, which means that the British will be coming by sea rather than by land. He then saddles up his horse and rushes off through the countryside, warning the citizens in Charleston, Medford, Lexington and Concord by shouting that the British are coming, and they should get out their muskets and get ready to fight a battle, which they did.

But that’s not what happened. And we know this because, among other things, Revere, who was indeed a messenger, wrote a report to his superiors describing what happened. Remarkably, in some ways, sort of, Palin had been right.

First of all, the British fleet had been in Boston Harbor for days, tied up at the docks there. This was 1775, not 1776. All of America was under British rule, and Boston had its soldiers everywhere, including in Town Hall. So the rebels had to work in secret. Two days before, Revere—who had dressed as an Indian, participated in the Boston Tea Party—attended a meeting at which the rebel leaders guessed, correctly, that the fleet was in town so the Redcoats on board could go from town to town all the way out to Concord, collecting along the way all the weapons the local citizens had. When they would get to Concord, they would attack and destroy the ammunition storehouse there, and they would arrest Samuel Adams and John Hancock, two of the lead rebels. This would all be done at night.

The rebels knew that the key thing they had to do was once the British started moving to get everybody along the way to Concord with their muskets before the British got there. They’d also have to know which route the British would be taking. There were two possibilities. To do this, the rebels would have to send as many messengers as fast as possible, and hope that at least one of them would not get caught.

They decided on two messengers, taking the two different routes. One, a man named William Ware, would go on horseback along the southern “land” route, through Back Bay and Roxbury and Brookline and then northeast to Cambridge and Concord. A second messenger, Paul Revere, would row across Boston Harbor to Charleston to then proceed along a northern route.

It fell to Revere that night in downtown Boston to keep a lookout to see if the British were getting into boats for a crossing to Charleston or were disembarking to take the southern route. When he knew which was which, he would inform Robert Newman, the Sexton of the Old North Church, to put lanterns up in the belfry. If it were one it would be the southern land route, if it were two it would mean the Redcoats were heading across the bay to Charleston. The church belfry was visible to rebels in Charleston.

At midnight, a dockboy ran to Revere and told him the British were starting to get into the boats to cross to Charleston. Revere told Newman and the two lanterns were posted.

After that, both Revere and Ware headed out on their different routes to Concord to get the rebels to gather in front of the warehouse and to warn Adams and Hancock to get off into the woods until the battle was over.

Revere had an oarsman quietly row him across the Bay to Charleston, where, on the shore there, he got, by prearrangement, a fresh horse from John Larkin, Deacon of the Old North Church, and off he went, several hours ahead of the British.

He went along, knocking on doors to wake people up, whispering in to those inside that they should head to Concord quickly with their muskets. He did this through Charleston itself, then all the towns along the way until he got to Lexington, six miles before Concord.

By this time, three other men had joined him in spreading the alarm. But in Lexington, there in the middle of the night, the men encountered six redcoats who told them to halt—they were under arrest. Two of the three got away and continued on to Concord, but Revere himself was detained. If he tried to get away, he later wrote in his report, the Redcoats told him, they’d “blow his brains out.” He stayed. They also wanted to know what he was in such a hurry about.

Revere told them. In fact, he told them everything. That there were 500 rebels heading for Concord and the Redcoats would be no match for them and there was nothing that they, the Redcoats, could do about it. His captors replied they 1,500 Redcoats were coming. Revere never did say that the Redcoats could not prevent the rebels from bearing arms, but that is, in essence, what he did say. He also lied about the number of Rebels. But as it happened, he wasn’t telling them anything they didn’t already know, and so they told him that. At that point, shots rang out. And with that the Redcoats decided to go off as fast as they could to join their forces going to Concord. As Revere would be a burden, they took his horse and left him with a tired horse that one of the officers had. They then cut the saddle bridle. Revere wouldn’t be going anywhere anytime soon.

There is no mention of any bells being rung in the middle of the night. It was all done by people knocking on doors and waking those inside. The British, after all, were the government in these villages. There was nothing good that would come from making a lot of noise.

As it happened, although there were skirmishes that night, the real battle at Concord did not take place until the next morning.

At the battles for Lexington and Concord, the rebels drove off charges by the Redcoats four times, inflicting many casualties, and then executed a surrounding maneuver which caused the Redcoats to flee back to Boston.

Revere went on to become a decorated rebel colonel in the war. After the war he became a wealthy businessman. He died at age 83 in 1818.

As for Sarah Palin, when asked if she’d like to revise her account of Paul Revere’s ride, she said no, she’d stand by it.

Go to Wikipedia and type in “Palin Revere” and you will read the four paragraphs of how the editors handled this dispute. There are over 240 footnotes, but there are only four “experts” who are quoted in the four paragraphs. Two say Palin was essentially right, the other two say Palin was dead wrong.

Go figure. [/expand]