Remembering Painter Lee Krasner

I first met Lee Krasner at the Marlborough Gallery on February 6, 1971, when I was 22 years old and a second-year graduate student. I had just completed a seminar on Abstract Expressionism, where Jackson Pollock was featured. Having decided to investigate Pollock’s debt to the art and ideas of Kandinsky, I decided to interview Krasner.

Krasner agreed to see me and arranged for us to meet in New York at the Marlborough Gallery, which then represented both her work and the Pollock estate. I arrived a bit early and was welcomed by the director, who led me to a table, handed me a catalogue, and said, “Here, you’d better read this. She’s an artist too.” It was the catalogue for Krasner’s first retrospective, held in 1965 at the Whitechapel Gallery in London.

Despite receiving positive critical reception in London, Krasner had not been included in the course I was taking, which was taught by a young male professor. Nor did her work appear in the big new book on Abstract Expressionism, which had just been published. Hardly surprising. At the time, I was teaching an introductory survey of art history, using a classic textbook, which, like the new book on Abstract Expressionism, contained no women artists.

I asked Krasner if Pollock had saved any books or exhibition catalogues related to Kandinsky. Krasner said I was welcome to come out to visit her on Long Island next summer to have a look for myself.

I spent several days that August researching in the library of her old house, where she let me stay in her upstairs guest room. I was fascinated by her wit, her humor and her ability to make history come alive. I was very interested in the paintings hanging in Krasner’s house. These included her early self-portraits from the time of her study at the National Academy of Design. I was fascinated to see that she had begun with such traditional figurative work. I was struck by the quality of her output, and I began to question why she had been left out of art histories from the period. This could have been her motivation in inviting me to visit, since much later I learned that she already had an inventory of the books I went to see.

By 1976, I was working as a curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art. I had the opportunity to collaborate on a show that would be called “Abstract Expressionism: The Formative Years.” I was eager to see Krasner in the show along with her male colleagues. When we divided up the artists, I chose to write about both Krasner and Pollock (among others) in the catalogue. I called Krasner and arranged to interview her and discuss loans for the show we were planning.

I encouraged Krasner to let us include in the show some works on paper that she had produced while still at the Hofmann School during the late 1930s. “Why that student work?” she wanted to know. I explained that it would document her interest in abstraction long before she met Pollock. So she let us select whatever we wanted of both hers and Pollock’s. I added some of her works on paper that were inspired by still-life set-ups from the Hofmann School.

Painted in brightly colored hues with the edges of objects no longer readable as representational, they looked abstract and made clear that Krasner’s ability and sophistication as an abstract artist predated her contact with Pollock. When our show opened, critics finally began to see that Krasner had been a significant artist before Pollock. They praised her work and, for the first time, they declared that Krasner was indeed a “first generation Abstract Expressionist.”

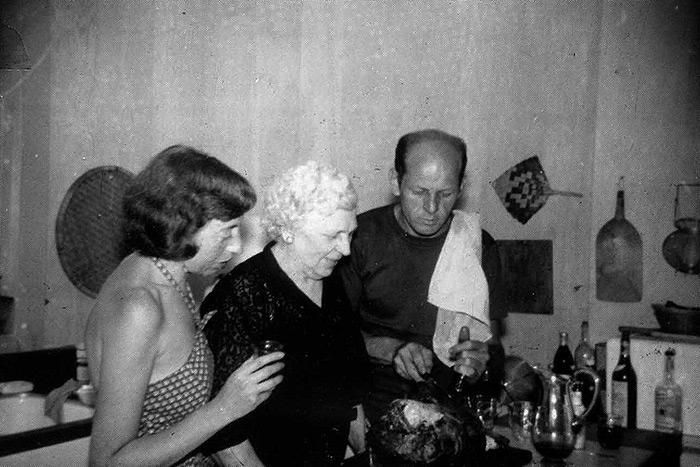

Krasner appreciated my intervention on her behalf. I believe that this formed a bond between us. After the show opened, I visited her in Springs on many occasions, sometimes spending up to a week or two at a time. Krasner often cooked for me when I visited. She taught me how to make her pesto sauce (with fresh basil ground together with pinoli nuts and olive oil), which she served slathered over broiled bluefish, an inexpensive fish very commonly caught in local waters.

I came to consider Krasner both as my mentor in the art world and as an older professional woman who had acquired experience and wisdom. I never forgot the impact Krasner had on my life. In 1989, five years after her death, I purchased a home in Springs, not far from Krasner and Pollock’s house, where I had had my most extensive visits with her. In fact, for me, she seemed to embody that distant part of Long Island.

Gail Levin is author of “Lee Krasner: A Biography,” published last spring. She will speak on August 12 in the Fridays at Five series at Hampton Library, Bridgehampton.