The Pelican: The Single Worst Fishing Disaster in the History of Montauk

It’s been 60 years since the Pelican disaster. Very likely, you’ve never heard of the Pelican disaster. It has been, over this time, something that people do not like to talk about. But 60 years is 60 years and perhaps the time has come. Lessons were learned. New laws were passed.

It is unlikely that anything like what happened to the Pelican, a Montauk fishing boat open to all comers, will ever happen again. In terms of lives lost, it’s sinking was the single worst maritime disaster out of Montauk in the 20th century.

The story of what happened aboard the Pelican goes back to World War II. On Fort Pond Bay in Montauk during that war, the Navy erected a series of concrete buildings, docks and hangers to serve as a torpedo-testing base. Torpedoes were manufactured in factories inland, shipped aboard the Long Island Railroad to the very end of the line, where they were unloaded at this testing base, fired out into the bay and, if they went straight and true, gathered up, repacked and shipped back to the Port of New York for distribution to America’s submarine fleet.

But then the war ended. And about a year after that happened in 1945, some smart entrepreneur got an idea to turn that torpedo-testing base into a fisherman’s paradise. Dozens of fishing boats would tie up at the docks there. The hangers and other concrete buildings would be converted to restaurants and clam bars, and a deal would be made with the New York Daily News and the Long Island Railroad. For a small fee, a sportfisherman in Manhattan, and there were many of them, could clip out a coupon in the Daily News, present it with the cash to the Long Island Railroad stationmaster in Penn Station at 4 in the morning, climb aboard a train with the name FISHERMAN’S SPECIAL blazoned on the side, and in two hours, just as dawn was breaking, tumble out of the railroad cars, run across the unused tracks at the Montauk station and climb aboard the waiting fishing boats.

The entrepreneurs starting this venture even had a splendid and very special name for the spot in Montauk. In 1942, the second year of the war, American planes, in a daring raid, dropped bombs on Tokyo. At that time, planes could not fly far enough to go from the American mainland to Japan, not even from Hawaii to Japan, so where had the planes come from? They couldn’t have come from any of the nearby islands in the Pacific because every one of them had been overrun by the still expanding Japanese Empire. After the raid, President Roosevelt spoke on the radio and told America about the successful raid, and said the planes had taken off from the Island of Shangri La. There is no Shangri La. Wasn’t then and isn’t now. And in Japan though the military people must have been scratching their heads as they turned the pages of their atlases, here in America, people knew that what he meant was that it was a secret and it would be kept secret until the war ended. As it turned out, Shangri La was later revealed to have been the American aircraft carrier Wasp that had steamed behind enemy lines to get close enough to Japan to do the raid. In Montauk, one year after that secret had been made public, the entrepreneurs decided their fisherman’s paradise would be Fishangri La. And so, that is what they named it.

If you look through history books out here, you will come across, as I have, a picture taken in 1950 of the sides of some Long Island Railroad cars at six o’clock in the morning. In the darkness, hundreds of fishermen, complete with boots, rods and reels, fishing hats and other gear, can be seen leaping across the tracks toward the camera, great smiles on their faces, as they headed for the boats. No doubt they came close to trampling the photographer who took that picture. He was just in the way.

Fishangri La did a terrific business in the summers of 1949, 1950 and 1951. But on September 1, 1951, the Saturday of Labor Day Weekend, something terrible happened, and things would never be the same again.

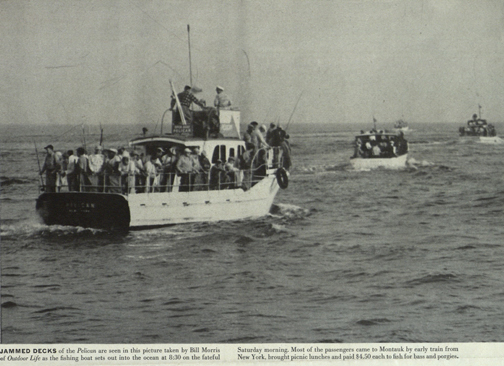

At six a.m., right on schedule, the FISHERMEN’S SPECIAL, its wheels squealing as the brakes were applied, pulled into the Montauk station and came to a stop. The men on board, letting out a rousing cheer, tumbled out and the whole lot of them, about seven hundred people, headed for the boats, running to board whichever ones had room. A total of 64 people of them climbed on the fishing boat PELICAN captained by Eddie Carroll. It was the greatest number of people he had had on board that year, but then, this was Labor Day Weekend, the biggest weekend of the summer. The blues and stripers were in.

The weather is a fickle thing at the best of times, but back then, even the weather forecasting was unpredictable. It had been only 13 years since the Hurricane of ‘38 had swept across eastern Long Island without the slightest advance warning. On the other hand, the fishing boat captains were all seasoned men. The wind was up. The day might be good, but it might not. If it was not, they would turn around and come back, and the fishermen, though disappointed, could enjoy the storm at the bar in Fishangri La swapping stories.

It is also important to note that having 64 people aboard a 42-foot fishing boat was not against the law sixty years ago. The Coast Guard had inspections as to the seaworthiness of the vessels. But there were no rules about how many people could be on board.

In any case, one at a time, the 21 fishing boats at Montauk that day started out from the dock as the dawn was breaking, and aboard the Pelican, Captain Eddie Carroll, hearing there was good fishing at a spot called Fisbee Bank, headed out the six miles to the Montauk Lighthouse, rounded it, and headed south.

The Pelican went out slower than the other boats. Only one of its engines was working properly. Nevertheless the Pelican was over the fishing grounds and the men pulling in the fish with great abandon for about an hour and a half when, around 10 a.m., Captain Carroll decided to call it a day.

With just his one engine he’d struggle to get back. Also the weather was turning bad. The wind was getting worse and the seas were rising. The fishermen grumbled a bit upon hearing of his decision, but they did what they were told. They would be heading back. The other boats would be heading back later.

Thus it was, with the rains beginning to fall, that they started back, not a particularly far distance, a distance that would usually take about an hour, but in this case might take two.

The storm got worse. And it was almost four hours later, just before two in the afternoon, that they rounded Montauk Point and headed the final few miles to port. On the leeside of Montauk Point, however, the waves were much worse. One of them, fifteen feet high, washed over the boat.

About 20 people crowded into the small cabin of the Pelican. The remainder of the people, still on deck, seeing a second giant fifteen-foot wave heading toward the starboard side of the fishing boat, rushed to the port side. And in one horrible moment, the wave hit, the Pelican rolled badly, and then turned completely over, throwing people into the water everywhere.

Help arrived in the form of some of the other fishing boats heading in through the storm. A ship called Bingo II captained by Lester Behan rescued twelve. Other heroic rescues in the heavy seas were made by Captain Carl Forsberg piloting the Open Boat Viking and shark fisherman Captain Frank Mundus of the Cricket II. But when it was over 45 people, including Captain Carroll, were dead.

Later that afternoon, the Pelican, still floating but upside down, was towed into Fishangri La by the Cricket II. Some of the bodies of the dead were laid out on the dock. It was a horrible, horrible scene and a great tragedy.

After the loss of the Pelican, President Dwight Eisenhower urged Congress to look again at the laws that regulate the fishing boats in America. New laws were passed, including one that would have limited the number of people who should have been on the Pelican to 35.

As for Fishangri La, it closed for the winter, then reopened the following spring and after the next summer season, closed for good. Some years later the buildings of Fishangri La were torn down. The condominium Rough Riders Landing today occupies the site where Fishangri La once was.

Why have you never heard of the disaster of the Pelican?

Well, one reason is that there are still people alive today who remember the sight of all those people laid out on the docks. Another reason might be best explained by the statement made by fishing boat Captain Howie Carroll, Eddie’s brother, who spoke at the hearing conducted by the Coast Guard after the event. The topic was whether or not Captain Eddie Carroll had handled himself correctly in protecting the lives of the people on board.

“My brother would never have endangered the lives of those people,” he said. “He was a chief boatswain’s mate in the Navy during the war, had a pretty good record. And something else. Maybe it’s irrelevant, but a lot of people that come down on the Long Island Fisherman’s Special, these people are not just customers. I mean, they are people who come out week after week to a special boat. I have them, everybody at the dock has them. It’s not just a matter of hustling at the dock. These people are our friends. Eddie would naturally try to protect these people.”

The Coast Guard ruled, and there is bitterness in this, that if Eddie Carroll had lived, he could have been found negligent in not directing the fishermen to balance the boat and in not radioing for help in time.

Needless to say, nothing like this has ever happened on the east end again, not in Montauk, Hampton Bays, Sag Harbor, Greenport, Riverhead or anywhere else.

May the lord have mercy on the souls of those lost September 1, 1951.

For a thorough study of this disaster, read Tom Clavin’s wonderful book Dark Noon.