Cullen's Encounter: The Local Hero Whose Actions Changed WWII

John Cullen died on August 29 at the age of 90. He was the last man with direct experience with the landing of German saboteurs in Amagansett during World War II. He met up with one of them within 45 minutes of when they came ashore, and as the saboteur did not follow the standing orders to kill anyone they met on the beach, Cullen got to live a long and happy life. As for the saboteurs, there were eight of them. Within 60 days, six of the eight were put to death in the electric chair. The remaining two were given what was essentially lifetime jail sentences. [expand]

Cullen was born in Manhattan, raised in Queens and lived his adult life in Westbury, employed until retirement as a salesman for the Dairylea (Milk) Cooperative. He was a sweet, baby-faced boy growing up, and in 1941, when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, he was just 21. He enlisted in the Coast Guard weeks after the attack and was posted as an ensign to the Coast Guard Station in Amagansett at the end of Atlantic Avenue Beach. (That station, awaiting restoration as a museum, is there today.)

Up until that time, the job of the Coast Guard had largely been helping mariners offshore when their craft became disabled, shipwrecked or grounded, rescuing swimmers and others in distress, looking out for smugglers and bootleggers (during the Prohibition years) and otherwise enforcing the laws of the sea.

In the days after Pearl Harbor, however, President Roosevelt received top secret news from American operatives behind German lines in Europe that the Nazis were planning to land saboteurs on U.S. beaches to go inland with explosives to destroy factories, railroad junctions, bridges and department stores. No point of landing was mentioned. The President took it very seriously and quietly ordered the Coast Guard to set up 24-hour patrols to walk the beaches along the entire east coast. He also ordered fortifications built. One such group of fortifications is today preserved as Camp Hero State Park near the Montauk Lighthouse. The forts included guns the size of those aboard battleships.

The order to build these forts and to begin the beach walks was carried out with astonishing speed. By May of 1942, just five months after Pearl Harbor, many of the forts had been built and the beaches were being patrolled as planned.

In Amagansett, the Coast Guardsmen were sent out to walk the beaches east and west from the station at two-hour intervals. One would go east for two miles, the other west for two miles. At the far end of the beach walk, there were little wooden booths where the Coast Guardsmen could warm up and rest for a moment and sign a chart with the time to confirm they had been there. Then they would walk back to the station. The round-trip would take two hours. Oddly, the Coast Guardsmen carried only a flashlight and a flare gun. If they were to encounter anyone who shouldn’t be there, they were either to take them into custody and bring them back to the Coastguard Station, fire a flare to get help or, failing that, try to leave the situation to run and get help.

As it happened, the new ensign from Queens, John Cullen, was one of the Coast Guardsmen assigned for the night shift walk in Amagansett. And so it was he who set out at midnight on the night of June 12-13 for what was supposed to be his two-hour walk to the east and back.

It was a warm, foggy night with no moon. He had walked along the crest of the dunes for no more than 10 minutes when he heard people talking and saw a man in fisherman’s clothes coming toward him. The man had apparently seen his flashlight. He was approaching him.

The conversation that took place, between George Dasch, 38, a former waiter born in Speyer, Germany, and John Cullen, 21, a college-age boy who had just joined the Coast Guard, has been written about many times. Dasch and Cullen had slightly different versions of it, Dasch in military court and Cullen to any eager reporter who asked him about it. It went something like this.

“Hello?” Dasch shouted.

Cullen shined his light on Dasch’s face.

“Who are you?” asked Cullen.

“Fishermen.”

“You’re not supposed to be out on the beach this time of night. It’s after curfew.”

“I know. Our engine failed and the boat washed up. We were out of Southampton headed for Montauk.” Dasch spoke in perfect English.

“You were out fishing at night?”

“It was light when we started out. But where are we?”

“You don’t know?”

“I don’t know where we landed. You would know.”

“You’re in Amagansett. That’s my station over there,” Cullen said. At this point, Cullen could make out the silhouettes of several other men down on the beach busy doing things near a boat.

“We’ll be fine,” Dasch said. “We’ve got her going again. We’ll just pull back out. Thanks very much.”

Dasch turned to leave.

“Wait a minute,” Cullen said. “What’s that all about?”

Cullen motioned with his flashlight to the water’s edge.

“It’s a military operation. And you’re in a very dangerous situation.”

“I thought you said you were fishermen.”

“This is a secret operation, from Washington. And if you come any closer, you will be killed. Leave. Now. Shine your light on my face.”

Cullen did so.

“We’re simulating a landing on the beach. I can’t say any more. Those men have orders to shoot on sight. Remember my face. You will see it again in Washington. Leave.”

Cullen didn’t move. “Come with me to the Coast Guard station,” he said. He put his hand on Dasch’s arm.

At that moment, one of the sailors called out to Dasch in German. “Was ist los?” He had lifted his weapon.

Dasch put himself between the Coast Guardsman and the sailor, and now in German shouted back to him. “I’ll handle this,” he said. Then, in English, which the sailor did not understand, he shouted, “Go back to the boys and stay with them.”

He looked again at Cullen.

Dasch pulled a roll of cash out of his pocket.

“Take this money. Here’s $100.”

Dasch held it out. Cullen would not take it.

Dasch tried again. “Here’s $300,” he said, peeling off more bills. This was an enormous sum of money in those days. “Take it.”

Cullen decided. He took it, and stuffed all the bills into his pocket and ran off into the fog to the Coast Guard Station to report what had happened. Dasch returned to the others on the beach.

Back at the Coast Guard Station, the officer on duty didn’t believe Cullen when he said there were Germans on the beach who had given him money to keep his mouth shut. But then they saw it and counted it. That made believers out of them. Phone calls were made. Men from a military encampment six miles away in Napeague were told to come. Other calls went to Coast Guard Headquarters in New York and to the New York office of the FBI.

As for the Germans, having changed from their naval officers’ uniforms into American-style fishermen’s clothes (bought in Berlin) before the encounter with the Coast Guardsman, they hurriedly finished up what they were doing—which was burying boxes containing high explosives, fuses and timers in the sand—scrambled over the dunes and into a potato field. After many hours of lying low in some shrubbery in that field, they proceeded to the Amagansett Railroad Station and took a pre-dawn train to New York City, where for several days they got lost in the crowds.

A week later, this incident was made public in a sensational press conference held by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover who announced that the saboteurs had all been rounded up before any harm could be done and were safely in jail (Dasch had turned them all in). Ensign Cullen was portrayed as a hero for what he did, similar to the heroic work done by Lieutenant Colonel James Doolittle, the American Air Force officer who had led the bombing raid on Tokyo from an aircraft carrier in the Pacific just two months before.

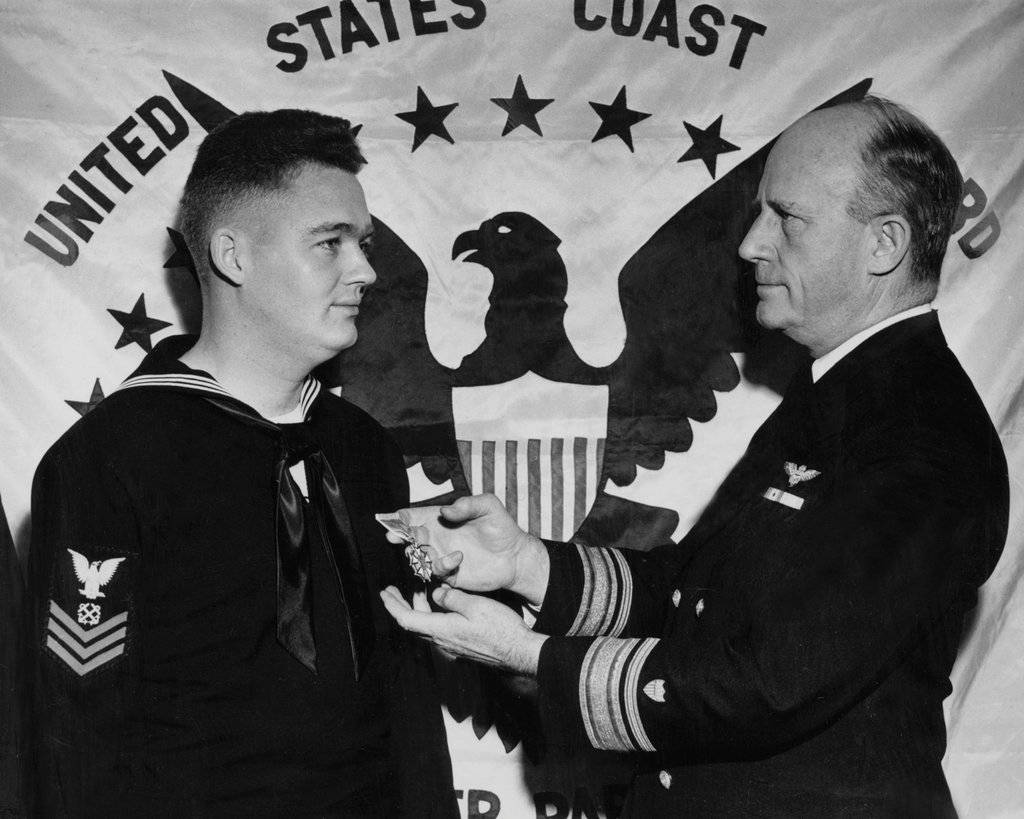

For the rest of the war, Seaman Cullen would sometimes appear at parades, war bond drives and ship launchings. He often talked to reporters. He received the Legion of Merit. And for the rest of the war he served as a driver for high-ranking Coast Guard officers.

John Cullen married the same year as the incident on the beach, and after the war lived a long and happy life here on Long Island with his wife Alice, his son and daughter and, ultimately, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Several years ago, he and his wife moved to Chesapeake, Virginia, to be near their daughter and her family.

George Dasch, who had turned the other seven saboteurs in, was one of the two saboteurs not put to death. He was sentenced to serve 30 years at hard labor, but in 1948, with the war over, President Truman commuted his sentence with the proviso that Dasch be deported to Germany with no ability to ever return to America.

This was a very bitter pill for Dasch. He may have been born and raised in Germany, but for 20 years—from the time he was 18 until just before the war started—he lived in America working for the most part as a waiter, including, as it happened, jobs at the Sea Spray Inn in East Hampton and the Irving Hotel in Southampton. He spoke nearly perfect English. He had, in fact, served honorably in the U.S. Army in the 1920s. And he had no history of supporting the Nazi cause. Indeed, Dasch had even married an American, a woman he left behind when he returned to Nazi Germany. He always claimed he had left for Germany to find work and after noting with alarm the vicious situation in Germany, came back to America to sabotage the Nazi effort and had no intention of harming any American.

That he did not shoot Cullen on sight changed the course of history. So did Cullen doing what he did.