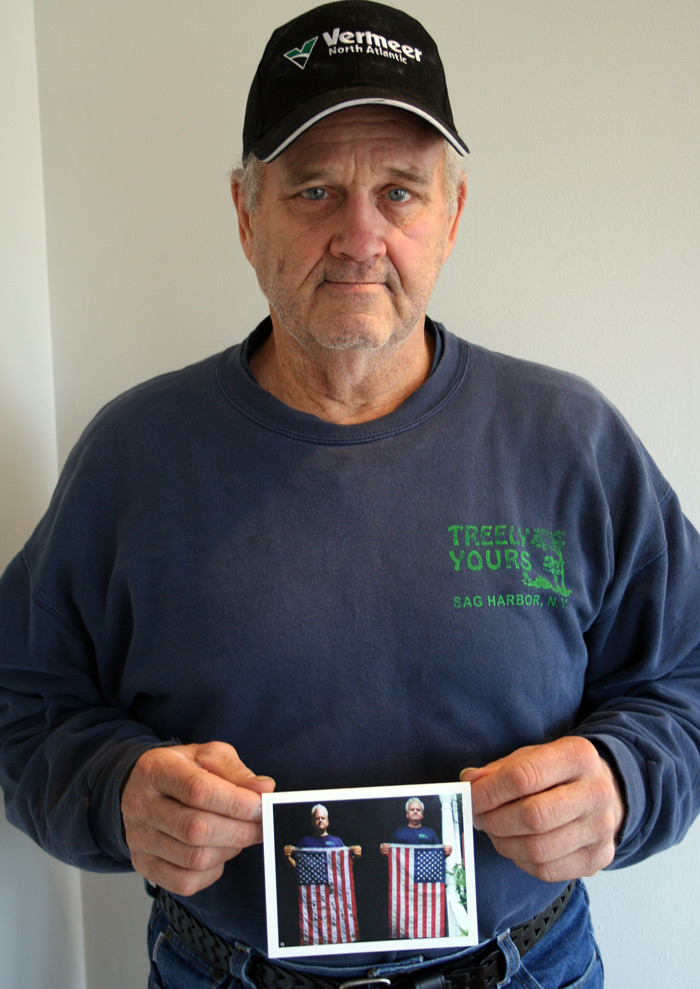

Who's Here: Richard Sawyer, Vietnam Veteran, American Hero

A number of years ago, back when the East End actually got snow in December, Sag Harbor resident Richard Jefferson Sawyer would dress up as Frosty the Snowman and clear the village’s sidewalks with his personal snow blower. His greatest reward for his helpful antics was hearing someone say “thank you.”

Sawyer is a Vietnam veteran, and the two-word phrase is a powerful one. As such, it’s become his mantra as he looks to help all those who have served this country by raising awareness of the deep, personal sacrifices of war and, in particular, post-traumatic stress disorder. [expand]

Sawyer’s latest project is creating notecards with his personal poetry that he hopes the National September 11 Memorial and Museum will give to people who makes donations. He wants the cards to help people to reflect on the importance of their donation.

Sawyer has designed two specific notecards for this cause. The first depicts an image of the Twin Towers taken on the morning of September 11, prior to the attacks. With the sun shining through the gap between the two buildings, a brilliant cross is formed. Sawyer’s poem honors all who lost their lives in the attacks, “They were heroes, all of them/ From janitors to CEOs/ They were all—Americans/ Dressed in different clothes.”

The second card contains a story of Sawyer’s experience on September 11. Shortly after hearing about the attacks, Sawyer, deep in thought, went for a walk in Sag Harbor and, to his shock and horror, discovered an American flag discarded in a garbage can. Removing Old Glory from her metal coffin, Sawyer took the flag to the tailor and dry cleaner to have her repaired, and she now hangs in front of his home.

“I like to think that I was symbolically helping to save my country, which was so viciously under attack,” Sawyer says about the significant timing of his find.

The idea for the September 11 cards, however, was born out of an earlier exercise in spreading awareness for the plight of returning soldiers. Born in Boston and a graduate of Long Island’s Freeport High School, Sawyer was attending Nassau Community College when he was drafted into the Vietnam War.

In an attempt to avoid deployment into Vietnam’s jungles, Sawyer decided to prolong his training in the United States, and so he signed up for a 90-day non-commissioned officer school in Fort Benning, Georgia, and then subsequently entered a 90-day specialized program to be in the K-9 Corps. The move to stay in the U.S. proved to be a double-edged sword, as Sawyer was in high demand once he finished his training. He was sent to Vietnam as a walking point—Sawyer and his dog would scout out the enemy territory ahead of the infantry for possible signs of the enemy.

“The experience changed me mentally,” says Sawyer. “I used to be very easygoing, but after I came home, nothing could be done fast enough. I talked fast. I was very impatient. And I had a temper.”

Eventually, Sawyer was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a mental condition that afflicts about 30% of Vietnam veterans and between 11 and 20% of veterans in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars.

Sawyer, however, prefers to refer to his condition as “soldier’s heart,” a term that he came across while reading his alumni bulletin from the private Stony Brook School. Coined by a Stony Brook University professor who fought in World War II and, soon after, experienced what most would call a nervous breakdown, “soldier’s heart” succinctly described what Sawyer felt upon returning home from Vietnam.

But, laments Sawyer, little is done to help soldiers impacted by PTSD. Motivated by a deep appreciation and understanding of what veterans endure both during combat and upon returning home, Sawyer turned to poetry to express his complex sentiments.

“His heart, though wounded, continues to beat,/ Going through life on wandering feet./ In search of a cure which will help him endure/ The pain he feels inside,” reads a potion of the Soldier’s Heart card.

Sawyer has since created numerous notecards to spread awareness of a variety of issues, and he gives them to customers of his Sag Harbor-based tree-cutting business, Treely Yours. Recently, his cards have gained a modicum of fame on the East End, as the Sag Harbor Whaling Museum and a solar installation company in Bridgehampton have both asked if they could to give them to their customers as well.

Sawyer’s primary focus, however, remains helping returning soldiers. He hopes to create a life-size Soldier’s Heart PTSD memorial in East Meadow’s Eisenhower Park. Shelter Island sculptor Jerry Glassberg has created a preliminary, 13-inch model, and Sawyer is working to have a full-scale monument erected in the near future.

Sawyer asked Glassberg to become a part of the project after a particularly moving experience on Shelter Island. While biking, Sawyer came across a clearing in the woods and noticed people sitting in silence. He decided to join them.

“I was getting in touch with nature,” recalls Sawyer, something, he quickly realized, he had never been able to do, while in Vietnam, the sounds of gunfire always dominated his senses.

After 20 minutes of silence, local psychiatrist Dr. George Nicklin got up to share his thoughts on war. Sawyer approached him at the end of the service and, upon disclosing that he had fought in Vietnam, Nicklin thanked him for his service.

Moved by his words, Sawyer recalled that “It was the first time anyone had ever thanked me.”

He soon realized that a simple thank you is all that a solider wants. He doesn’t want any special treatment—simple recognition of the sacrifices he and his comrades made for this country is enough.

Sawyer recalls contacting Glassberg after reading a story about how the artist created a bust of Dr. Nicklin.

A man with an incredible energy, Sawyer’s journey through life has been marked by fascinating experiences. And he hopes that his empathy and persistence will ultimately benefit those who endure his pain.

Sawyer secretly wishes that someone would coax him or, rather, “Frosty,” out of his retirement, as he genuinely misses the smiles that greeted his character as he strutted down Main Street. But, for now, he is answering to a higher cause. And it is his tireless efforts to better the lives of vets that deserve the ultimate “thank you.”

Sawyer hopes that those who read this story will be moved to action. Donations to the 9/11 Memorial can be mailed to One Liberty Plaza, 20th Floor, New York, NY 10006; 911Memorial.org.