That Murder: Remembering the Brutal Death of Investment Banker Ted Ammon

The murder of investment banker Ted Ammon traumatized the Hamptons 11 years ago. Ammon was murdered in his bed in his mansion on Middle Lane in East Hampton early in the morning on October 21, 2001. Even though he was alone in the house with an elaborate security system, an intruder had gotten in, disabled it, snuck upstairs, found him asleep alone in the master bedroom, and beat him to death. After that, the intruder left. There was no robbery.

Ammon’s battered corpse was found two days later when he failed to call in or show up at work at the firm where he worked in Manhattan. One of his business partners, a man who liked Ammon very much, volunteered to fly out to his house in East Hampton to see if he was here. What a terrible scene he found.

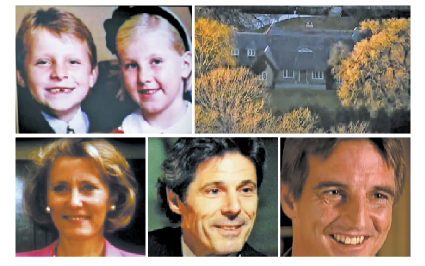

Soon after, a local workman, the very man who had installed the surveillance system, was arrested. In a sensational 2004 trial that gripped not only this community but the rest of the country, the nation learned that Ammon and his wife, Generosa, were separated and going through a bitter divorce and that the workman, a married man named Daniel Pelosi of Manorville, had begun having an affair with her. Ammon’s wife was at this time living in the Stanhope Hotel in Manhattan not far from her husband, but had just bought a townhouse in need of renovation. That’s when she met Daniel, who had come into the city to take on the work. Soon he had virtually moved in with her and the two 11-year-old children she’d adopted with her husband. As for Ammon, he worked in the city, did see his children, and sometimes went to the mansion in East Hampton on weekends.

In the course of these events, the separation, the bitterness, the murder, the investigation and the conviction, the two people that all of us felt most sorry for were the Ammon’s two children. Indeed, just two years after the murder, Generosa came down with breast cancer and died. For the last few months of her life, her children were essentially raised by their longtime English nanny, Kathyrn Ann Mayne. She tried to shelter them and keep them from harm as best she could. Though Mayne was given guardianship in Generosa’s will, the children eventually went to live with Ted’s sister Sandi Williams in Huntsville, Alabama. Also in the will, Mayne can live in the East Hampton house for the rest of her life. The twins are now adults, age 21.

And then on July 29, 2012, suddenly, they were in the news, in the New York Post, which revealed that all the tens of millions of dollars, $50 million in all, that Ammon left after he died, after taxes, had been largely doled out to law firms, accountants, executors and so forth so the amount now accruing to the children was a relative pittance. At the end of it all, each child gets $1 million.

COURT OF GRAVE ROBBERS, the Post headlined. All these people and law firms, who are, according to the Post, lawyers Gerard Sweeney and Michael Dowd, the law firm Schulte, Roth & Zabel, the executor JPMorgan Chase and various accountants, had their benefits and fees approved at the time by surrogate court judges in Manhattan and on Long Island, including Judge Eve Preminger. These benefits and fees are, the Post says, nearly four times the amounts that court administrators deem acceptable.

“Former Manhattan Surrogate Eve Preminger approved $4.3 million to a single firm, Schulte, Roth & Zabel,” the Post wrote. “That amounts to $9,710 per day between February 2002 and July 2003.” The Post adds that Preminger had connections to the firm. The attorney who was the pointwoman from that law firm on the Ammon case, they say, was lawyer Susan Frunzi, who wrote a textbook with Preminger entitled “Trusts and Estates Practice in New York.”

The Post published a chart showing where the $50 million went. There were $15.5 million in taxes, $10 million in the court approved fees, $10 million to charity (The Ammon Foundation), $10 million to a trust of Generosa Ammon, now deceased, and $1 million each to the twins and the nanny. And that’s it.

At the trial, the jury took 23 hours of deliberations to convict Daniel Pelosi. Afterwards, one of the jurors, Rosemarie Brady, told The New York Times “we tried very, very hard to pronounce him innocent, but the evidence was overwhelming. Pieces just seemed to fall into place.”

There had been no witnesses to the crime. No fingerprints that showed Pelosi had been there. It was all circumstantial, but it was enough.

It was learned at the trial that the surveillance system that Pelosi installed could have the house’s surveillance screens monitored from a remote location. The remote location was at Pelosi’s sister’s home in Center Moriches. Pelosi could spy on Ammon from there.

Late in the evening on the night of the murder, Pelosi came by his sister’s house to look and see who was at the Middle Lane home. Then he left, with a buddy he said, to go out and get some beer. He did not return. The security system had not gone off that night. Pelosi knew the system’s code. Also at the trial, a former girlfriend of Pelosi’s testified that he had confessed to her that he had killed Ammon, who he said begged for his life.

Pelosi’s father testified that after the murder, his son had come to him to ask what was a surefire way to hide something.

There was also evidence that this was all about the money. A few years earlier, Ammon had crafted a $25 billion takeover of RJR Nabisco. But when his divorce proceedings began, Generosa was told Ammon’s fortune was less than $100 million. He had lost the bulk of his larger fortune in the economic downturn that had ensued after the takeover. But Generosa didn’t believe it and complained bitterly to Pelosi that her husband was hiding his money. Matters proceeded from there.

At the trial, Pelosi took the stand in his own defense and it was a disaster. By this time, he was accusing Generosa, now dead, of being the actual person who had inflicted such huge mayhem on Ted Ammon that night. It was she who wanted the money. He also threatened both the prosecutor and the jury, saying things would happen if he were convicted.

* * *

This past June, I got a letter from a student studying journalism at SUNY Westbury asking if I would read and critique what she wrote for a class assignment—which was to interview somebody in jail. She’d interviewed Daniel Pelosi, who, in the piece she wrote, claimed he was innocent and if she came back he would give her the proof. I did my best to help her in her writing. She then wrote again to thank me but then also to say she had come back to the jail but now he had refused to see her. I did not hear from her after that.

It’s hard for people today to wrap their minds around what happened on Middle Lane all those years ago. A book was written about it, but it was not a best seller.

It did remind me of another terrible murder that occurred many years ago on Long Island. The wife of one of the Woodwards—someone who people thought was particularly mean and nasty—heard noises during the night, her husband had gotten out of bed and into a bathrobe and off to investigate and, after awhile, she got up, took with her a loaded gun and shot who she thought was the burglar. It wasn’t.

This story also got national play. And at the sensational trial that followed, she got off and got the inheritance. This was in the 1955, though, and though over, not forgotten by the Woodward family.