A Conversation with Bill Pickens, Activist

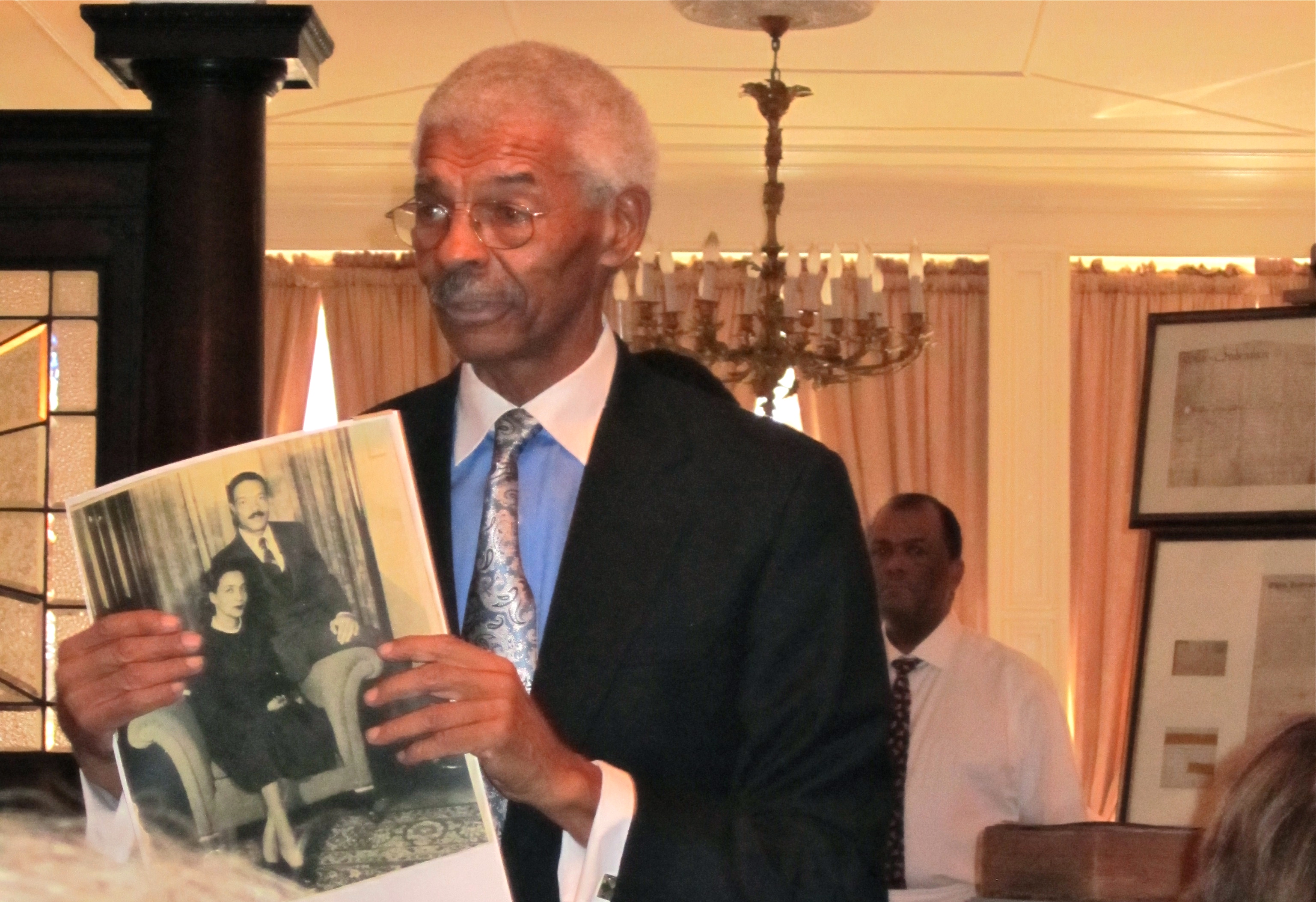

Such places include The Golden Pear in Sag Harbor, where Pickens recently held forth during this interview. Unknown to him, he’d attracted an interested eavesdropper who gushingly said hello on her way out and thanked him for all that she had heard. To say that William Pickens III is an institution on the East End is an understatement—he’s a walking history lesson who, if he knows he’ll be talking about his family’s over-300-year history in this country, carries with him samples for show and tell—first editions, documents, photographs. Just a couple of weeks ago he participated in a panel discussion at the Southampton Historical Museum’s “Bells Are Ringing” 150th anniversary celebration of the Emancipation Proclamation. The speakers’ table was covered with Pickens memorabilia and, needless to say, he spoke without notes, going over once again, with pride and enthusiasm, some of the highlights of his ancestors’ careers. The list includes Aunt Ida, “an honors graduate of Smith,” he beams, who became the first black WAVE officer, thus integrating the Navy. So many in his family were “the first African American to…” a phrase that easily applies to Pickens himself.

A 1954 graduate of Franklin Lane High School in Queens, he says he was always active in school politics and encountered no racial problems. The times were different, then, he points out, no drugs, no poverty, no gang warfare. Because he wanted to go away to college, he enrolled at the University of Vermont, “a liberal college in a liberal state.”

Pickens majored in history and political science and thought about pursuing a law degree. When he was elected president of the student body, he recalls that the school newspaper wrote: “Pickens is the first black president, let us hope he’s not the last.” He was also president of the senior men’s honor society and president of the then mostly Jewish fraternity Tau Epsilon Phi. After graduation, he found himself in the reserve commission of the 5th Air Force as Second Lieutenant and Personnel Officer, a position that took him to Japan, where he studied Japanese language and culture.

In the service, he again enjoyed life relatively free of racial incident, though one day going to the movies with three white buddies (it was 1958 and in the South), he remembers being told that he could use the back door and then sit in the balcony. “Good enough to be in the military but not the cinema.” The four of them left.

How ironic, he reflects now—he had freer access in Japan, “this black cat from Brooklyn” who as Chief of Administration for his division was evaluating a 330-man squadron, “guys from the South.” He subsequently traveled all over Southeast Asia, “a tall black man, a curiosity,” but never an object of ridicule.

Back in the States and tending to family business (his father had recently died), he took on several managerial and executive training posts, including being a supervisor at the Western Electric division of Bell. He later worked with labor unions, a “great test” for a black man then. He kept getting recruited for consulting positions at prestigious organizations such as Booz Allen Hamilton, and at banks (Marine Midland) and Phillip Morris, though he “wasn’t a smoker,” he adds, a fact that would prompt him to move on. Finally, he founded Bill Pickens Associates and was invited to join Robin Chandler Duke, Angier Biddle Duke and Rabbi Arthur Schneier as a founding advisor of the U.S. Japan Foundation, funded by entrepreneur Ryoichi Sasakawa.

Other memories, still potent, bubble up—especially those that involve his beloved mother and her long-time friend Rachel Robinson, wife of Jackie Robinson. Bill was 10 when “JACKIE ROBINSON CAME TO MY HOUSE!” (It’s likely that folks outside The Golden Pear could hear this one!) It was 1947, when Robinson was named Rookie of the Year, and he gave Pickens a baseball. Later, at the University of Vermont, Pickens invited Robinson to give a talk, but a snowstorm intervened. Oh dear, the university was going “gaga” over Robinson. Could Roy Wilkins make it? Alas, no, but Wilkins knew this 26-year-old up-and-coming minister from Alabama. Who? Martin Luther King. No, Pickens recalls saying, about the little-known King, “that wasn’t such a great idea.”

Pickens is extremely proud of his brilliant grandfather, William Pickens Sr., “a 1904 Phi Beta Kappa graduate of Yale University, a Lincoln scholar, a skilled linguist in five languages (including Greek and German), and one of the founders of the NAACP.”

He also talks passionately about his great-great grandmother who was severely whipped as a slave, but who “spoke up, spoke back.”

He could go on speaking about his family, achievements that he’s putting into a book he’s begun to write based on recollections from both his father and mother’s side—free blacks, freed blacks—11 generations of “documented Americans” he says with a smile, adding what his grandfather used to say: “The mission is to enlighten blacks and endarken whites.”

America is increasingly becoming a brown country, though the news is slow to arrive. Some people refer to Barack as “Obama”—and Pickens says, Barack Obama is not “this” president, he is “our” president.