Historic Blizzards Sink Ship Off Hamptons Coast

The tough weather we’ve been having this winter reminded me of a terrible time in the Hamptons when people on shore watched helplessly as 28 people died onboard a ship just 400 yards offshore Mecox. The ship was stuck on a sandbar and the men were trying to unload its cargo when a vicious winter blizzard appeared on the horizon. As the storm approached, people on the beach urged the captain in charge, also on the beach, to order the workers ashore. Instead, the captain ordered the men to remain on board and finish the job. And so came the disaster.

The ship Circassian was built in Belfast, Northern Ireland as an oceangoing freighter with sails and a steam engine in 1857. It was 242 feet long, had an iron hull and with the engine at full throttle could do 14 knots carrying a full load of 1,700 tons across the Atlantic in two weeks.

During the American Civil War, which began four years after the ship was built, the English owners sent it running the naval blockade imposed by the North on the South, carrying supplies to the Confederacy in return for cotton from the plantations there. In 1863, while trying to run this blockade, she was spotted and captured by a Northern gunboat, taken to New York and fitted with heavy cannons, to serve for the rest of the war as a mail and supply ship for the North.

After the war, an American company bought her, removed the cannons, and used her to ply the Atlantic coast, bringing goods to ports from as far north as Maine and as far south as Charleston. At one point, she ran aground at Sable Island, Maine requiring a salvage company to pull her off. Another time, she ran aground at Squan Beach, New Jersey. After that happened, she was taken out of service for three years, only to be sold to another English firm who sailed her home, took out her engine and turned her into an iron-hulled three-masted schooner and put her back on the trans-Atlantic line.

The English firm did have trouble for a time getting a crew to work her. With her various adventures, she was considered something of a jinx. Nevertheless, she made the crossing carrying freight uneventfully for the next

19 years.

In the 19th year, however, on what was supposed to have been her last voyage, she left Liverpool at the end of November, and along the way, came to the aid of a ship in distress in the mid–Atlantic. She took aboard 12 members of the crew before that vessel sank, and took them to New York. There she was turned around, and on December 11, 1876, early in the morning, was sent off back to England, fully loaded with furniture and fabric and carrying a crew of 49. It would indeed be her last voyage, but not like one anybody expected. It was a sunny, cold morning when she left New York Harbor, but by midafternoon a blinding snowstorm had come up. The captain, Robert Wilson, steered her through the storm on a compass setting, but the compass was not working right. At 11 p.m., in the freezing cold, he ran the Circassian up on a bar at Mecox, about 400 feet from shore.

The ship was soon spotted through the storm by surfmen on the night shift at the newly built Mecox-Bridgehampton Life Saving Station, just in its fourth year of service. The surfmen sent messengers on horseback to the Life Saving Stations in Southampton and Georgica, and by morning, as the storm abated, these three crews began to make attempts to reach the Circassian though the freezing cold waters.

At that point, of course, the whole town knew about the ship at Mecox. That Monday morning was supposed to be the first day of the Bridgehampton Literary and Commercial Institute’s winter term, but William T. Halsey, one of the young students there, later said “was there school that a.m.? I should say not.” Everyone was down at the shore.

As everyone watched, this large group of surfmen dragged an old Francis lifeboat out of the garage and across the sand—their new Beebee surfboat was on loan to the Philadelphia Exhibition and had not yet been returned—but they could not get it through the rough surf, though they kept trying. By 11 a.m., they were successful, however, and they rowed the short distance out to the ship, brought the ship’s officers back to shore and took them to the telegraph office in Bridgehampton nearby to send a message to the ship’s agents in New York City. By late in the day, a tugboat from New York appeared and the crew threw lines to the Circassian. Other lines were wound around the ship’s capstan and attached to anchors thrown overboard. The tug would pull and the men would crank the iron capstan and reel in the lines against the anchor to, hopefully, also try to pull her off the bar. But it was not

a success.

That evening, Captain Perrin of the Coast Wrecking Company, an agent of the owners, arrived by train from the city and took charge of the operation. They would continue to try to pull the ship free, but at the same time, they would commence to unload the cargo to shore.

The next day, it was raining and the winds were whipping. Captain Perrin had, by this point, hired a local man, Charles A. Pierson, to carry out the combined operation from shore and he in turn had hired Captain Luther Burnett, a man proficient in the handling of small boats, to run the ferrying operation back and forth. Late in the morning, Pierson appeared with 13 workers from the area he had rounded up, 10 Shinnecock braves and 3 local men. Although by this time, all 49 crewmen had, in seven trips, been taken off, 16 of them agreed to go back on to join with the other laborers for the extra pay. Captain John Lewis and three engineers also went out there. And so, on this choppy day, the operation began. Unfortunately, it was going to be slow going. There was a huge amount of cargo. It was expected it might take a week

or more.

After two weeks, however, the job was not done, though indeed, the ship had shifted on the bar. It had moved nearly 100 yards. But it was still 250 yards from shore and still stuck. Unfortunately, what nobody knew was that below the ocean surface, this iron ship was beginning to break up. The cargo being unloaded was coming out of the central cargo area first and this was a mistake. The center of the bottom of the ship is what sat on the sand. Doing it this way put great pressure on both the fore and aft parts of the boat. It wouldn’t hold up.

And then the worst thing imaginable happened. With all those men back out there on the boat, late on the afternoon of December 29, another enormous blizzard appeared on the horizon heading toward them from the northeast. The lifesaving men, all men who lived in this community, urged that all the workers be brought to shore in surfboats until the storm passed. But Captain Perrin was having none of it. He said they should continue with their work. He also pointed out that when the ship came free, which it would when the new storm lifted the ship on the high tide, he’d need the men on board to sail it. And then, to make his point, he angrily ordered the one single safety line, from ship to shore, cut.

On board, upon hearing this, Captain Lewis said,“We’ll float tonight or we’ll go to hell.”

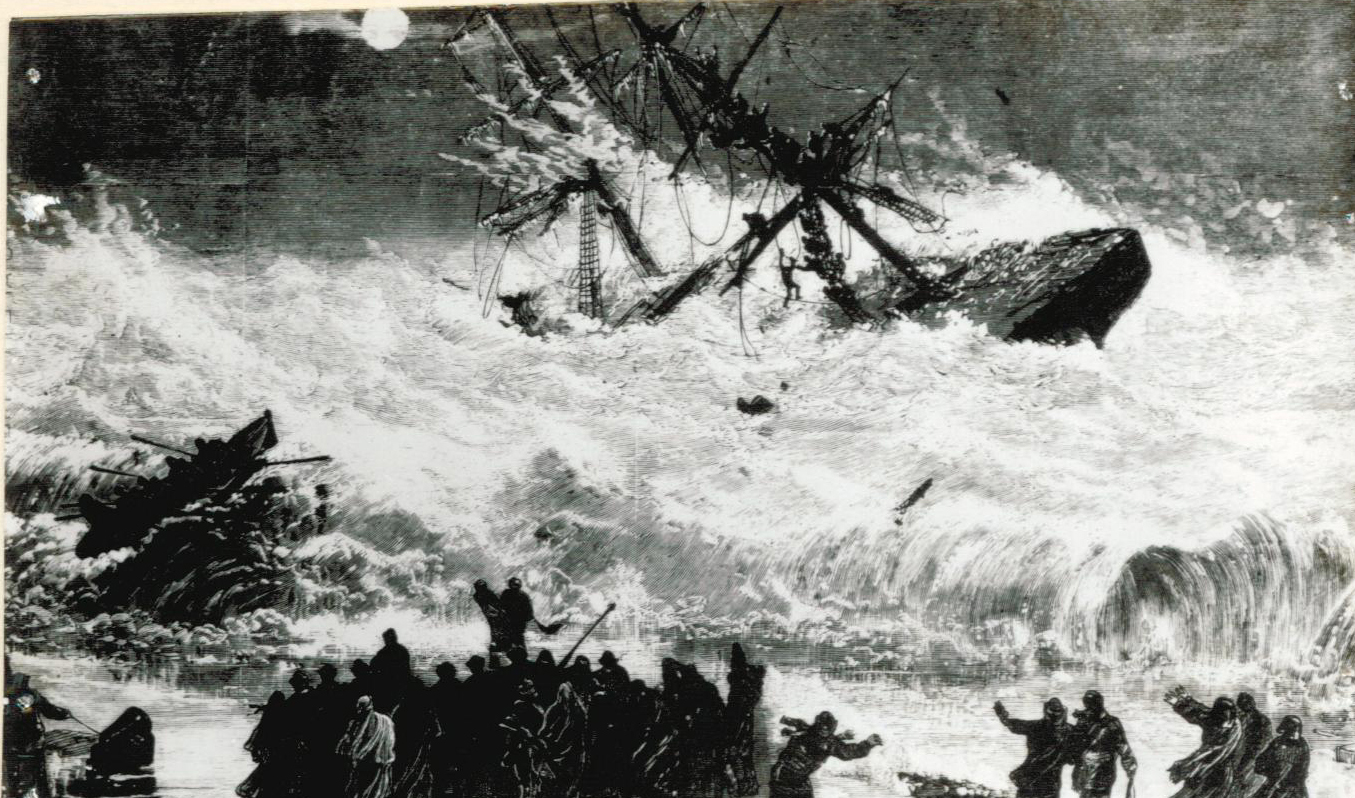

Within the hour, however, the temperatures plummeted and this second blizzard, one even worse than the first hit the shore with great fury. No further boats could be brought out. At times you couldn’t even see the Circassian through the blinding snowstorm. But you could hear those on board. As the ship was settling, the sea was now washing over the deck. And so you’d see the men, fighting to get away from the cold sea by climbing up the masts.

As day turned to night, the men out there cried out and screamed, and now Perrin relented. But getting boats out was hopeless and even the attempts to get new lines out to the ship failed. The surfmen had trouble keeping tapers lit so they could fire the cannon that would send the line out, and when they did succeed the lines, heavy with sand, salt and spray, would tangle up and fall short. At this point, the high tide came, and the surf began washing up to the back dunes and over them, causing the surfmen to scramble to move the Marby Mortar to newer further-back locations, even further from their target. Eventually, the attempts were abandoned. The storm continued. The ship did not move.

Occasionally, there would be a glimpse of the fore and aft masts, tipped at angles to one another as the ship broke in two, these masts all filled with men frozen to them, a ghastly sight. Late that night, one of the surfmen, Captain Charlie Barnett, said he heard the Indians singing “Nearer My God to Thee.”

There could be no survivors. Or could there? Just before dawn, as the storm abated, the surfmen sent out a team of 18 men with lanterns to scour the beaches looking for bodies. Amazingly, they arrived just as four men, alive and clutching a large cylindrical piece of cork used to keep cargo from shifting, came through the surf. These men had tied ropes around the cork, had clasped hands and feet over and under it, and had held their breaths as waves overcame them. The surfmen rushed out into the surf to get them and bring them in. They were the first and second mate, a carpenter and an engineer seaman. In the end, three survived, and the fourth died. There were no other survivors.

The bodies of the local men along with the 14 sailors were buried in the Old South End Cemetery in East Hampton.

The 10 Shinnecock braves who died were David, Franklin and Russell Bunn, Warren, George and William Cuffee, John and Lewis Walker, Robert Lee and Oliver Kellis. The 10 Shinnecocks were taken to the reservation and buried there. A monument was erected to their memory. As for the tribe, the men left nine widows and 25 orphans. The tribe was devastated.

In the Southampton Historical Museum today, you can see the letter that Teddy Roosevelt wrote in 1898 when he was out on the East End with his Roughriders and saw how the tribe was suffering. His letter is addressed to the Hildreth Store, and it refers to the $217 that was enclosed. This money was to be distributed weekly to the bereaved Indian families.