Thomas Moran Trust Progressing in Restoration

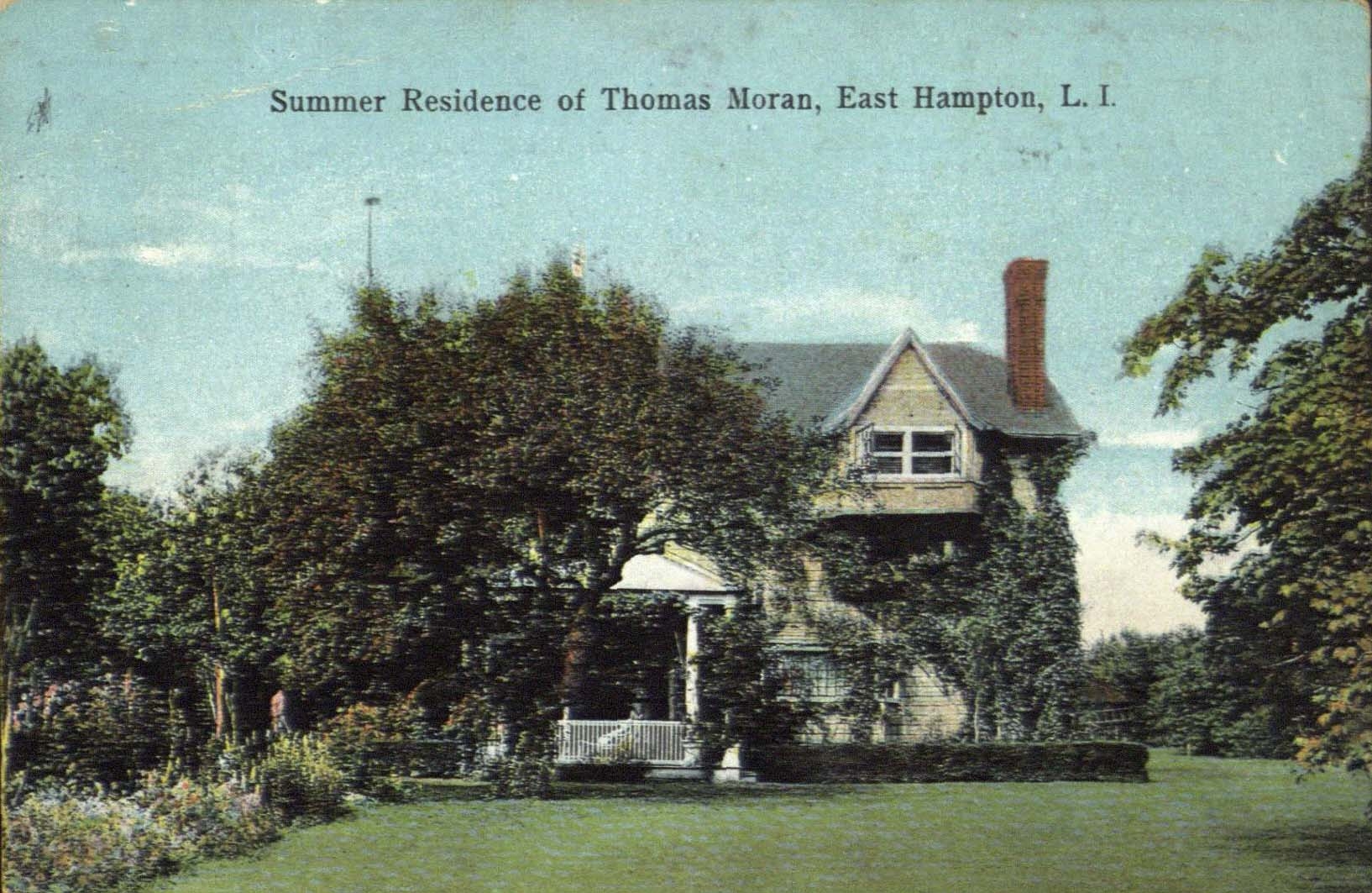

You’ve seen it but haven’t seen it—the historic Moran house, set back from Main Street across from Town Pond in East Hampton. It’s the home and studio where Thomas Moran (1837–1926), his wife Mary Nimmo Moran (1842–1899) and their children lived beginning in 1885. More visible in winter, its neglected exterior hardly suggests its significance. It was designed by Moran himself and was the first artist’s studio built in East Hampton. In the Morans‘ day, it was likely the area’s liveliest social, artistic and cultural gathering place in the summer. Both Morans worked there, though Mary, a prominent landscape painter and printmaker, was not as well known as her husband, who was one of the most celebrated oil and watercolor artists of his day.

Though closely associated with East Hampton, Moran’s fame began with the painting Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone which he completed in 1872 after going west with a U.S. Geological Survey team. The painting, it has been said, influenced the establishment of the National Park System.

“The Studio,” as the Moran house is known, is one of the “very few structures that have been restored from that summer colony period,” says Richard Barons, the East Hampton Historical Society Executive Director and newly appointed Executive Director of the Thomas Moran Trust. He is delighted to be on board as Phase Two of the restoration begins, the “hard hat period.” Phase One, which just ended, began in 2007 when the 501(c)(3) Thomas Moran Trust was formed, to the delight of many.

Of course, Barons is looking forward to Phase Three—“planning and programming for public enjoyment of the property” and the creation of educational components, particularly different age-appropriate group tours.

Described in Moran Trust literature as a “quirky Queen Anne-style studio cottage,” the Studio includes not just family rooms and service wings, but the gardens and walks, which, Barons notes, are generating a lot of community interest. As historian Robert Hefner has written, the house was an “architectural departure from the conventions of the time” because it integrated living space and an artist studio under one roof. This was an unusual move which determined The Studio’s “essential simplicity, its modest scale and its informality.” As the Trust material also notes, the Queen Anne style (popular in America from 1880–1910) consisted of “asymmetrical composition.” among other details, “notably the corner turret with steep cap.” But Moran added his own touches, and he also imported “a gondola from Venice that he used on Hook Pond.” He also saw to indoor plumbing and electricity.

Mary Nimmo Moran died in 1889, and Moran summered for 22 years more before moving to California. Daughter Ruth Moran lived in The Studio until her death in 1948, at which point the property was bought by Condie and Elizabeth Lamb who had it declared a landmark in 1965. In 2004, following Mrs. Lamb’s death, the property was willed to Guild Hall. Four years later The Studio, outbuildings and gardens were deeded to the Moran Trust to assure “restoration, preservation and accessibility to the public.”

Barons points out that Phase Two involves removing 20th century features, carpeting and odd pieces of furniture, and also erecting stabilizing braces and other support structures. Mulford Farm is now housing molding and edging pieces and disintegrating “Celtic swirl” fireplace tiles, which will be re-grouted. They’re gorgeous, says Barons, “with dark amber shiny glaze,” and truly reflective of the period. But it’s the “extraordinary gardens” that cause him to light up, a labor of love that will be headed by garden historian Mac Griswold of Sag Harbor.

As the restoration comes along, Morans are at the ready: Guild Hall recently acquired a Thomas Moran at auction, and the Parrish Art Museum has a marvelous collection of etchings by both Thomas and Mary.