Railroad Stories: Wrecks, Wars and Nazis on LIRR

Here are six brief East End stories from the colorful history of the Long Island Rail Road.

First a little background. Originally, before railroads, long trips were an arduous affair by stagecoach and people rarely took them. Mostly, they would take trips, when they had to, of 10 to 15 miles. And so when the first railroads were built, they were built by local people for short distances to accommodate the traffic that would want that. Thus, in the 1830s through the 1860s, there were as many as a dozen individually owned railroad companies on Long Island started up, with names such as the Brooklyn and Jamaica, the Flushing Railroad, the North Shore Railroad and the South Side Railroad and so forth. One of them, started in 1834, was for a grander plan.

Major D. B. Douglass imagined a railroad down the center of Long Island to Greenport, from where, by using a ferry purchased from Cornelius Vanderbilt, he could take passengers to Connecticut and from there to Boston. He started this business, called the Long Island Rail Road, in 1834, and in the years that followed, in fierce competition with the other smaller railroads, he gobbled them up one by one, finally bringing service to Hampton Bays in 1869 and to Sag Harbor in 1870. Thus did the Long Island Rail Road become a monopoly for service on the Island.

Douglass’s original plan, to provide fast service to Boston, came to failure. Not long after he started the LIRR, a rival company built a railroad that directly connected New York and Boston. The Long Island Rail Road went into bankruptcy. And then things started happening. Here are the highlights.

ATTEMPT TO BUILD A CITY IN

FORT POND BAY

In 1880, a vigorous Manhattan businessman named Austin Corbin brought the Long Island Rail Road out of bankruptcy. He had a grand plan for a part of the lonely, barely used East End part of the railroad. This was the track that had gotten as far as Amagansett. Corbin extended the line out to Fort Pond Bay in Montauk, where he built six different sidings. He planned to make it a very busy place.

In 1894, he petitioned Congress to make Montauk a duty-free port. At that time, the way goods got from Europe to New York was by cargo ships that traveled through the ocean, along the south shore of Long Island, and then up through the Narrows to the Port of New York. Big ships traveled only about 18 knots. Then, if they got to the Narrows at the wrong time, they had to wait for high tide to get over the bar there, which could take up to six hours at anchor. Fog was also an issue. No one dared through at night.

Corbin began to let the word out. After Congress made Montauk a duty-free port, big ocean liners and freighters would dock at Fort Pond Bay in Montauk, the goods and passengers would be loaded into railroad trains out on wharves, and from there they would be whisked off to Manhattan at a mile a minute—in less than two and a half hours. It would save an entire day compared to the old way of getting things to New York.

This plan electrified the Port of New York, and the Mayor of that city to try to stop it. They enlisted the Army Corps of Engineers to say the bay was too shallow. They wanted to deny Corbin’s planned tunnel under the East River. But it was no use. The bill was headed for passage in 1896 when, on June 4 of that year, Austin Corbin, vacationing in New Hampshire, was thrown from a carriage drawn by runaway horses and killed. His dream died with him.

AMERICAN ARMY TO MONTAUK

In 1898, just two years later, the US Army won a triumphant victory over the Spanish in the Spanish-American War. Coming home from Cuba after the surrender was signed there in Santiago, President McKinley learned that many of his 29,500 American soldiers had come down with tropical diseases—yellow fever, typhoid, etc.—and were too sick to be allowed to come straight home to the parades and ceremonies that awaited them in small towns across the United States. It could cause an epidemic. Instead, McKinley asked if there were a place on U. S. soil where the soldiers might come to recuperate for a month before going home. The place would have to be inaccessible except by rail, undeveloped, windswept and sunny, but near where the great troopships might land to disembark the army to the waiting medical teams.

Thus it was that the entire army, 29,500 strong, came to Fort Pond Bay to tie up at the wharves already built there, and were taken to an encampment of several thousand white tents spread across the landscape. Among those landing there on August 14, 1998, was the national hero of that war, Teddy Roosevelt, who stood at the railing when his troopship arrived, to shout down to reporters about how he was happy he and his Rough Riders and the army had won, but sorry he was in such bully good health while so many other soldiers were suffering so much from illnesses.

President McKinley visited Roosevelt here. The main headquarters building was Second House, which became part of the Teddy Roosevelt County Park (now Montauk County Park). Three years later, after McKinley was assassinated, Teddy Roosevelt, the war hero who had become his Vice President, became President of the United States.

THE GREAT PICKLE WORKS WRECK

At 4 p.m. on Friday, August 13, 1926, a Long Island Rail Road train left Manhattan at 3:45 p.m. for its regular high-speed trip—along some stretches at 70 miles an hour—headed for Greenport. This was the famous parlor car train, where men sat in easy chairs in the first-class cars, smoking cigars and having cocktails made by white-coated attendants. Among them on board was Harold Fish, a stockbroker and wealthy aristocrat who had, as many wealthy people did, a large summerhouse on Shelter Island. His family would meet him at the Greenport station in their automobile and take him on the short ferry ride to that island so the family, together, could enjoy the weekend.

There seemed nothing unusual about this trip at first. This was the fast train, the Shelter Island Express, the pride of the railroad. It made few stops along the way. And it got to Greenport, 100 miles away, in less than two and a half hours. (The Hamptons version of this was, and still is, “The Cannonball.”)

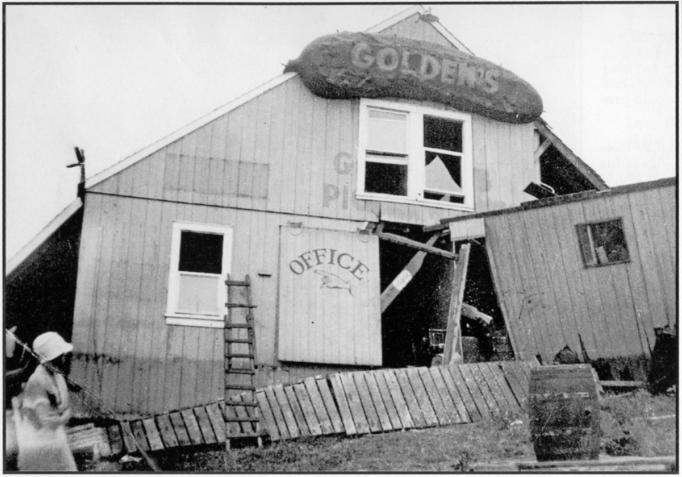

About three-quarters of the way out from Manhattan, in Calverton, just to the west of Riverhead, the train usually roared by an amusing-looking little factory. People would look out the window at it. The factory was at the end of a railroad siding, not 100 feet from the main line, a big wooden barn in which barrels of pickles, bags of salt, tubs of brine and bottles and caps were assembled and, on conveyor belts, packaged to be sent off to markets in Manhattan. It had, up on the eaves, above the highest window, a giant sign in the shape of a pickle. Upon it was the word GOLDEN’S.

Inside that factory, that day’s shift was to end at 6 p.m. The foreman, however, seeing as how it was Friday and it was quite a hot day in that barn, had everybody put the wooden lids over the brine, tie up the salt sacks and clean up at 5 p.m. so everybody could go home at 5:30 p.m. He locked up around 5:35 p.m.

At 5:45 p.m., a man in a farm truck on a dirt road had stopped at a railroad crossing a quarter mile before the pickle factory. He had come to a full halt. When the Shelter Island Express came roaring through, you didn’t want to be on the tracks. Indeed, off to his left, he saw it, coming on, blowing its horn. He was, as it turned out, the only person to witness the Great Golden’s Pickle Works Wreck.

The train that day was being pulled by Locomotives No. 2 and 214, two of the biggest and most powerful engines in the railroad’s possession. On board was the engineer, the fireman, the brakeman, several parlor cars filled with people, and several regular cars.

As this man in the truck watched, engine 214 suddenly leaped into the air, turned sideways, drew engine 2 behind it, and then the rest of the train down the siding tracks in a great tangle of dust and smoke, directly into the empty pickleworks building, where it all came to a halt with a gigantic crash. The building with everything in it collapsed, the sign came down, and it was just a complete disaster.

The man in the truck got out and ran to the scene. He was soon joined by the Calverton fire department, the police, an ambulance service and, after a while, some soldiers from the nearby Army training base, Camp Upton.

A woman and two children died in this accident. So did the fireman and brakeman, who the injured engineer found dead under tons of hot coals in the coal car. Also dead was stockbroker Harold Fish, found inside the factory, buried under piles of white salt spilled down from barrels that contained

them overhead.

It was one of the worst train wrecks ever in the history of the railroad. Investigations later determined it was due to the failure of a bolt that kept the switch from turning the locomotives onto the siding. The switch was halfway, neither here nor there, and the train went where it went.

The Golden’s Pickle Works Factory, of course, was never to rise again.

TORPEDO TESTING

Beginning around 1905, a series of fishermen’s shacks began to spring up along the shoreline of Fort Pond Bay. These shacks, about 50 of them, comprised what was then known as the Village of Montauk. There was no other community in Montauk at that time. This was it.

The shacks were built by fishermen, most of whom were from Nova Scotia. They’d be fishing out in the Atlantic and, instead of bringing their catch all the way home every time their holds were filled, they would come to the arc of this beach and unload their fish into the boxcars at the barely used railroad terminal there. Then, of course, the fishermen would want to rest up awhile. So that’s how it started. All the land, of course, belonged to the railroad.

By 1935 this village consisted of three dirt roads running parallel to the bay. There was a fish house, a post office, a school, a restaurant, a tavern. It was a thriving squatter community by the time the vicious Hurricane of 1938 came through, causing the bay to rise up and flood all the homes and throw them off their underpinnings. Nobody was killed, but the village was just about over.

A few hardy souls remained, and an attempt was made to build the place back up, but then in 1941, with the outbreak of the war, the Navy requisitioned the property, tore down the remaining shacks, and built on it a torpedo testing station. There were at least a half-dozen large buildings on the site, including a laboratory, storage facilities, barracks and a seaplane hanger. Until the war ended in 1945, the place was alive with people in uniform.

The torpedoes, built in factories in Queens, were put on railroad trains heading to Montauk, unloaded and stored there and tested in the bay. They’d be loaded with dummy charges, set and fired off into the bay toward targets, with the bubbles trailing behind them to show their trajectory, and with one of the two seaplanes circling around overhead to see if they hit the target. If not, they would be repaired on the site, if possible, and tested again. If they did hit, they’d be packed up onto the railroad trains and shipped out to war zones.

After the war, these buildings sat vacant for 25 years. Then, for 15 years, they were the site of the New York Ocean Sciences Laboratory, a research facility that was linked up with Columbia, Cornell and half a dozen other such institutions that would send their students there for two-week courses. After that, the buildings went vacant again. The whole thing was bulldozed to the ground around 1990 to make way for the Rough Rider Landing condominiums.

THE MOST DANGEROUS PASSENGERS

In the pre-dawn hours of June 13, 1942, four Nazi saboteurs were brought quietly from a German submarine to the beach at Amagansett with intentions of blowing up factories, bridges and terminals across America. They buried explosives on the beach, and then had an encounter with a U.S. Coast Guardsman on watch to look for just that kind of activity.

The Coast Guardsman ran off and sounded the alarm, resulting in a combined operation by the Army, the Navy, the FBI and the Coast Guard itself to find these operatives. But they were unable to do so.

What they didn’t know was that the saboteurs had scampered along through the farm fields until they got to the Amagansett Railroad Station (next to the firehouse.) No one was there when they got there at 4 a.m. They changed into fishermen’s clothes and sat on a bench outside until a stationmaster came and unlocked the station and sold them tickets to New York City (“How’s the fishing, good?” “Yup.”), after which they boarded the 6:57 a.m. headed in to Manhattan.

Going on that day in Manhattan—and this is an unbelievable coincidence—was the biggest parade in the history of the United States, either before or since. Six months earlier, on December 7, 1941, the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor and America declared war on Japan and Germany. As that was just two weeks after the glorious Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade in Manhattan, it was almost immediately decided at that time not to hold a Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade in 1942. However, in February of 1942, Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia had second thoughts.

If they couldn’t have a Macy’s Day parade that year, they would instead, on June 13, 1942, hold an even bigger parade! It would be called “New York at War.” It would be a parade of tanks, anti-aircraft guns, fighter planes, military units, marching bands and all sorts of other organizations anxious to show their solidarity in what was to be done with Hitler and Tojo. There were giant 30-foot-tall floats of these dictators, being bludgeoned with hammers and stabbed with knives as they were carted up Fifth Avenue. More than 2,000,000 people came to watch this parade.

And in the midst of it, four nervous German saboteurs got off the train at Penn Station, climbed up to the street and watched as the latest Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters soared across the sky. They immediately checked themselves into a hotel. And on June 19, one of the four, the leader, went to the FBI and turned the others in.

THE KIDS WANT NO SCHOOL

In early November of 1967, two East Hampton High School students and one out-of-town boy visiting his grandmother decided to try to arrange for the Long Island Rail Road train to crash into the school.

The school, at that time, was on Newtown Lane (it is the middle school today), and in a field just behind the school there were the Long Island Rail Road tracks. Every Sunday at 7:08 p.m., a very important-looking train, called the Cannonball, would come down the track from Montauk, heading west, filled with well-to-do passengers, and after stopping in East Hampton and the other stations in the Hamptons, would continue on nonstop to Manhattan. It made the trip in less than three hours.

Just before it passed behind the school—it was hard not to notice this—there was a spur of track that went from the main line to just behind the Schenk Fuel Company, less than 100 yards from the school. On days when the train had a big oil delivery, the switch would be pulled and the train would go out the siding and the fuel tanks would be filled up.

And so this was their plan. It was very simple. They’d go out there early that Sunday afternoon with a hatchet, break the metal pin that held the switching device in place, and pull the lever. Nobody would be in the school. Whatever came down after that, and it would be going about 40 miles an hour, would turn onto the siding. And that would be that. No school Monday!

The boys tried mightily to break the pin with the hatchet, but failed. One went home and returned with a hacksaw from his dad’s basement workshop, and that broke it. Then they pulled the switch down. The train would veer off the track. Then all of them left.

After they went to their respective homes, two of the three boys got cold feet. First, one returned and moved the switch back. Then the second returned and, not knowing the first boy had been there, moved it back the other way.

A dozen or so waiting passengers were at the East Hampton station that evening, waiting for the arrival of the train. They peered down the track, and soon, around 7 p.m., the front headlight of the train, right on time, appeared way down the track, heading in from Amagansett. Suddenly, this light veered off into some trees. What had happened?

On board the train, heading along at the expected 40 miles an hour, the engineer pulled up the throttle to begin slowing down the train for the station beyond. But then he saw the switch was the other way. He hit the brakes, but it was too late.

The train turned onto the siding, bashed through the small stop at Schenck Fuel, and then slid onto the lawn heading toward the school. It plowed up about 40 yards of lawn, which piled up against the front of the metal cowcatcher, and it came to a halt—stopped by the pile of lawn—just 20 yards from the school.

Four passengers on the train were injured. One of them, as it happened, was the wife of Walter MacNamara, the Chief of Special Services for the railroad, who every weekend came out with his wife to their summer home in Montauk. They were now attempting to return to Manhattan. But they never made it on

this train.

It took five days and $100,000 for the railroad to clear the wreck and fix the damage, during which time the three boys confessed to what they did. It turned out they were all 13 years old.

A lot of detention was served during the rest of that year.

WEB EXCLUSIVE

AMERICAN ARMY TO MONTAUK

In 1898, just two years later, the US Army won a triumphant victory over the Spanish in the Spanish-American War. Coming home from Cuba after the surrender was signed there in Santiago, President McKinley learned that many of his 29,500 American soldiers had come down with tropical diseases—yellow fever, typhoid, etc.—and were too sick to be allowed to come straight home to the parades and ceremonies that awaited them in small towns across the United States. It could cause an epidemic. Instead, McKinley asked if there were a place on US soil where the soldiers might come to recuperate for a month before going home. The place would have to be inaccessible except by rail, undeveloped, windswept and sunny, but near where the great troopships might land to disembark the army to the waiting medical teams.

Thus it was that the entire army, 29,500 strong, came to Fort Pond Bay to tie up at the wharves already built there, and were taken to an encampment of several thousand white tents spread across the landscape. Among those landing there on August 14, 1998, was the national hero of that war Teddy Roosevelt, who stood at the railing when his troopship arrived, to shout down to reporters about how he was happy he and his Rough Riders and the army had won, but sorry he was in such bully good health while so many other soldiers were suffering so much from illnesses.

President McKinley visited Roosevelt here. The main headquarters building was Second House, which became part of the Teddy Roosevelt County Park (now Montauk County Park). Three years later, after McKinley was assassinated, Teddy Roosevelt, the war hero who had become his Vice President, became President of the United States.