Welcome to the Hamptons: Stargazer, Linda Scott, the Disaster at ARF and What Happens Next

Since this is the beginning of the summer, I thought this might be a good time to tell the story of the beginning of the Hamptons, the 50-foot-tall Stargazer sculpture that sits in farmer Harvey Pollock’s field on the eastern side of County Road 111, just before it ends at the Sunrise Highway and you head off into this community.

Every kid in a car passing the Stargazer wonders what it is. Very few parents know the story of it. All they do know is that it marks the beginning of the Hamptons, of all that fun from Dune Road to Dan’s Papers to the Candy Kitchen, the Bay Street Theatre, East Hampton Town Pond and the Montauk Lighthouse.

Who in hell would go to the trouble of building such a soaring, monumental piece of sculpture? And why?

The creator of it is Linda Scott, a remarkable blond woman who grew up as part of the New York social set in Southampton and Manhattan. Her parents were Helen and Walter Carey of Captain’s Neck Lane, Southampton and Sutton Place. She went to St. Timothy’s Boarding School, Sarah Lawrence University, did guest studies at Harvard, got a further degree at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, then studied with Nick Carone, who recently got a Pollock-Krasner Foundation Lifetime Achievement Award. She has devoted most of her life to monumental works of sculpture such as Stargazer. Her work has been exhibited at the Fogg Museum in Boston, the Parrish Art Museum in Southampton, Guild Hall in East Hampton, the Elaine Benson Gallery in Bridgehampton and many, many other places. A drawing of hers is in the collection of Steven Spielberg. Another is in the collection of Audrey and Henry Koehler.

Scott has been married twice, first to investment banker Lawrence Flinn Jr., and then to sculptor and professor Richard Pitts of the Fashion Institute of Technology. And she has a son, now grown, Morgan, who went to Putney and then Bard and who now works in film and television production. But she’s left all of that for art and has lived at Luna Farm on Parsonage Lane in Sagaponack for many, many years doing her work.

The Stargazer is a “connection between the above and the below,” according to Scott. There’s certainly no doubt that it is. It soars to the sky, a deer nibbling on an antler, and it is best seen with the rising sun behind it over Mr. Pollock’s field to the east, one of the most inspiring works of sculpture imaginable. One could hardly expect an entrance to the Hamptons to be markedby anything else as extraordinary as this.

The Stargazer was commissioned in 1991 by the Animal Rescue Fund on Daniels Hole Road in East Hampton as a proposed entrance to their 10-acre property there across from the East Hampton Airport. It was to be tall enough for cars and trucks to drive under. It was to straddle the entire driveway. It was to inform you of your entrance to a place where animals could be adopted and others taken care of in safety from the ravages of man and nature.

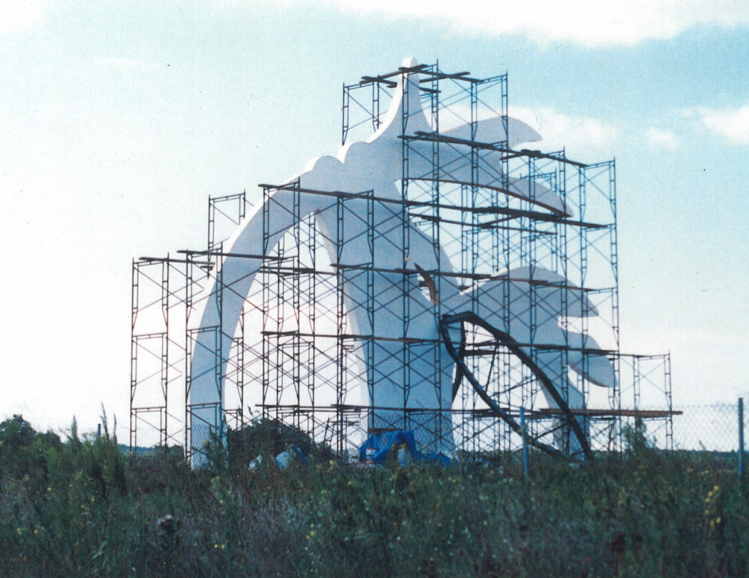

Scott made sketches of this monumental work. And she took these sketches up to the barn of a builder in South Fallsburg, New York, David Morris, where it was, at a cost of $200,000, fabricated into a series of pieces that could be bolted together with 14 fasteners. The wood panels were added. The stucco was added, the dark red paint was added. In pieces, it was then trucked down to one of the hangers at the East Hampton Airport, where it was assembled and taken by the Trocchio company to a grand outdoor cocktail party and ribbon cutting, where it was supposed to be erected and applauded.

This turned out to be one of the most dramatic and worst events ever. Family and friends and art lovers had assembled. The word came down that East Hampton Town Supervisor Tony Bullock had ordered that it not be put up—it was a “sign,” he said. And it was way larger than any sign that could ever be allowed to be put up in the town. It lay by the side of the road, the workmen from the Trochio company not required to do anything further.

A legend has risen up around the drama of that grand opening party. There are those today who say the sculpture could not be put up because it was considered a distraction and a possible hazard to pilots approaching the runway. Helen Harrison, the director of the Pollock-Krasner museum in Springs, recently wrote it was not put up because it was considered too dangerous. But, according to Scott, these are not true.

“Although they may have been true,” Scott told me. “There was a lot going on around this. Years later, I ran into Tony Bullock and he apologized, he said he had made ‘a terrible mistake’ in doing what he did. Anyway, it would have to be moved.”

Scott was urged by some to file a lawsuit against the town, but some of her friends, most notably Elaine Benson, told her “you live in this community, don’t do it,” so she didn’t.

Then, miraculously, she learned that a farmer in Manorville would allow her to assemble it on his sod farm in that town by the side of the road at the entrance to the Hamptons, 40 miles away. “Harvey Pollock told me Stargazer would be welcome, for the next 50 years, anyway,” Scott said.

And so it was in Manorville that Stargazer came to its full height, an iconic entrance to the Hamptons. It’s been there ever since.

Scott owns Stargazer. But she has to raise money to take care of it. She has done so now for more than 20 years. In June of 1996, vandals attacked the Stargazer, which, after just those five years, was already so well known that the attack was written about in The New York Times by Stewart Kampel.

“The steel, wood and stucco sculpture…has been spray painted and parts of the base have holes that appear to have been kicked in,” Kampel wrote.

Scott told him it would cost $50,000 to repair. “I won’t go down this way,” she said. “No maniac is going to finish off me or art.”

Soon, with money and material and labor donated by a paint company, a lumberyard and other private citizens, it was fixed. It stands proud. In recent years, its care has been taken over by Geoff Lynch, the owner of Hampton Jitney, whose busses pass alongside it while ferrying people from Manhattan to the Hamptons and back, 30 or 40 times every day. Photographs and artwork of the Stargazer wrap the sides of Hampton Jitney busses as a colorful homage to this community and its artists.

Once, at a low point in her life, Scott asked filmmaker Peter Brook what she ought to do next. Here’s what he said.

“Make a two-year plan. Do something heroic.”

Scott has a vision that her Stargazer sculptures—and there are other giant images that impart the same message as this one—can appear in locations around the world, bringing peace and harmony to the planet. A statement about her objectives says “we are the conscious relationship to the universe. We are responsible for our planet and its future.”

She has, on several occasions, erected other monumental “Stargazer” sculptures in the Hamptons, of heads looking upward, of hearts with knives through them, of more abstract concepts connecting above and below. Most have remained up a few years, but then come down. She has also fashioned jewelry collections that have been sold at Pelletreau in Southampton and at London Jewelers in both East Hampton and Southampton. Architects have made sketches of buildings incorporating the design concept of Stargazer.

Anyone interested in Stargazer, wishing to contribute or learn more, visit lindascott.org.