It Takes a Village? Hampton Bays Hamlet, Like Others Before It, Ponders Incorporation

I was going to open this story with a sentence that would begin “The powers that be in Hamptons Bays…” but then thought better of it. There are no powers that be in Hampton Bays. And that’s the problem. Therefore the humble unofficial citizenry of Hampton Bays are now considering breaking away from the larger entity in which they currently reside—Southampton Town—to make themselves an official Incorporated Village.

If they decide that incorporation is a good idea, they will announce boundaries, get permission from the state, and then have the people vote on a referendum. If a majority votes Yes, the place will henceforth be known as the Incorporated Village of Hampton Bays, and it will be filled with “powers that be.” There will be Mayors, Sergeants at Arms, Judges, Police Chiefs, Village Clerks, Inspectors, Trustees and all sorts of other posts.

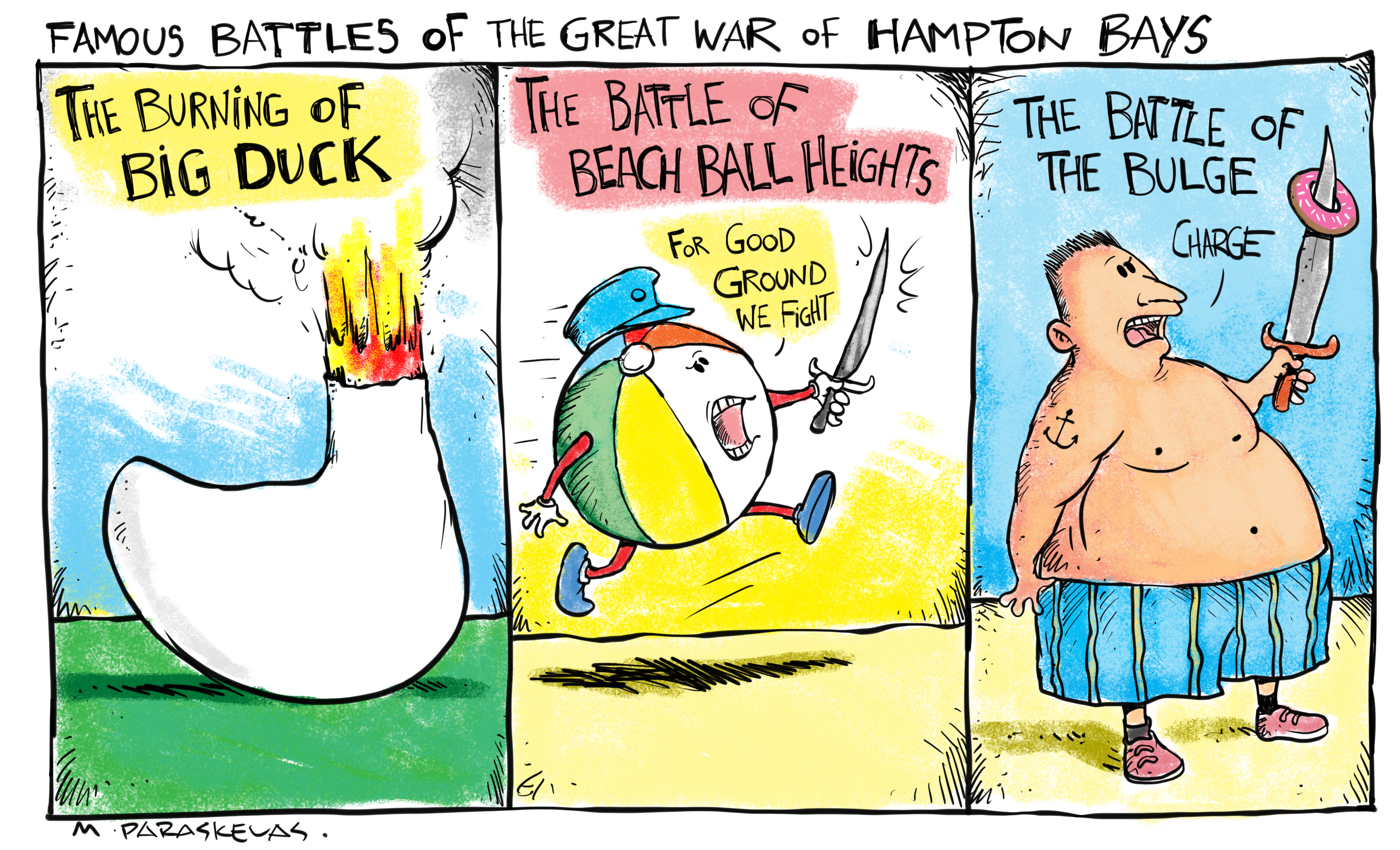

They might also consider changing their name. In the 1740s, the place was called Good Ground. It’s a good old name. Indeed, on the four corners in the center of town there is a concrete commercial building that, when built, was carved with the name Good Ground up top under the eaves. You come into the unincorporated village of Hampton Bays and you look up and you see the original name of the place, carved in stone, but that’s not the name anymore. It’s an eerie feeling.

They could incorporate as the Village of Good Ground.

There are plusses and minuses to incorporation. The plusses are that you have a new layer of government that is very nearby and will respond quicker to what is going on. The minuses are that you have a new layer of government that is very nearby and will respond quicker to what is going on, but will likely cost more.

As the founder of this newspaper, I can report to you that during my half-century tenure, there have been several attempts to create Incorporated Villages. All attempts were different one from the other. But two succeeded and are successful villages today. They are the Village of West Hampton Dunes and the Village of Sagaponack, both of which were carved out of the Township of Southampton.

It’s interesting to consider the fates of all these attempts separately. Perhaps Good Ground might learn something from such a consideration. Here they are from east to west.

There have been several attempts to incorporate Montauk. A serious attempt was made in 1966 but failed. A further attempt, in 1996 led to a straw poll of the residents and that also failed. Nevertheless the Town of East Hampton, out of which it would have been carved, paid attention to these rumblings and offered all sorts of inducements to Montauk, hoping that the rebellion would subside, which it did. Today, there is a police annex in Montauk, a Town Clerk’s office and a Montauk Citizen’s Advisory Board established to advise the East Hampton Town Board on matters relating to Montauk. None would be here today if not for these rebellions. It’s sort of like what happened in Canada where everything spoken or written in public has to appear twice, once in English and once in French. Quebec wanted to break away and form the French speaking Country of Quebec. But the rest of Canada, the English-speaking part, created compromises, among which was the dual language law, so Quebec has voted to stay a province. Sacre Bleu!

In 1987, a section in the western part of the Town of Southampton incorporated itself into the Village of Pine Valley. There were about 800 people in this village. It included the Riverhead Jail, the Suffolk County Center, Wildwood Lake and the woods around it and the people living in it, and a small part of Flanders, particularly along Peconic Bay.

The incorporation was spearheaded by founder Leonard Sheldon—and many believed his developer friends—who envisioned a new downtown, waterfront activities and lower taxes. After incorporation, when taxes went up and no new downtown appeared, the villagers became angry. Many villagers wanted to un-incorporate. Those still favoring incorporation tried to head them off. A battle ensued and in the end, those wishing to un-incorporate won. But it was not without angst. Three years later, the scattered remnants of Pine Valley were back in the capable hands of Southampton Town.

Jim Dreeben, the owner of Peconic Paddler in Riverhead, was a “resident” of this village during the brief time Pine Valley waved its flag, and he wrote a letter to Dan’s Papers reporting on things he claimed to have heard at the raucous village meetings. Here are a few choice quotes:

“It is NOT a conflict of interest. He is just a friend of mine and I think Pine Valley should pay him $875.”

“We appreciate your asking those fine questions, Larry—now sit down. You too, Alan.”

“We are being sued by developers.”

“Accomplishments? Now let me think. Oh, yes, we have a village hall, a copying machine, matching desk blotter, carpet, curtains and toilet paper.”

“The taxpayers who can afford these (outrageous) taxes are, in fact, the ones who want to dissolve the village.”

“I am not a politician. In March, when I became Mayor, compared to Pine Valley, Romania will look like Sesame Street.”

“I am here in an advisory position only. You pay me $175 per hour to listen and $250 per hour to talk, plus $5 per mile and dinner.”

“The Ethics Committee is overworked, what with all these crooked politicians.”

Without a doubt the most financially successful incorporation was the western end of Dune Road in the Town of Southampton. There were more than 500 houses on this part of Dune Road before jetties were built along that road to the west. When these jetties, 15 of them, were completed, the sea rose up where other jetties were never completed, and took away over 140 homes, wiped out the land, destroyed the single road, telephone, electric and sewage and ultimately created an enormous inlet with the sea rushing into the bay.

For a time, you could buy a half-acre of underwater oceanfront land for $5,000. I received such an offer.

But I considered it ridiculous, like throwing your money away, like buying the Brooklyn Bridge.

Today, after the Army Corps of Engineers built a mile-long giant steel cofferdam, the inlet was healed, the land restored, almost all the homes rebuilt, and if you want to buy a plot, it will set you back at least a million dollars.

Incorporation did that. It’s a longer story than can be told here, but it’s the case.

This was an attempt, in 2003, to create a preposterous Incorporated Village. In the end it failed. It was proposed to be along the five miles of oceanfront between Wainscott and Flying Point, but only 100 or 200 yards wide. The idea was to give control of the oceanfront to the residents along the ocean. Erosion control projects could then go ahead. Perhaps a village could prevent outsiders from accessing the beach. As it strung itself across the ocean frontage of Sagaponack, Bridgehampton, Mecox and Water Mill, you could see that at certain points, there was no contiguous road connecting one part of the new proposed village with another.

Since a great majority of the people along the ocean were in favor of creating this new village, there was only one way to stop it from happening. One of the unincorporated communities it would pass along would have to incorporate. It would be a dagger through the heart of this pencil thin proposed entity.

BRIDGEHAMPTON

The unincorporated met to consider incorporation. I think they met twice about it. They decided they liked being part of the Town of Southampton. Being a new village would be an added expense.

SAGAPONACK

On the other hand, the citizens of Sagaponack, which is among the most well-to-do communities in America, decided to put an end to Dunehampton, and did. Their incorporation took place in 2005 and all indications are during its short eight years that it is a considerable success. It is well-run, many of its required services, such as police or fire, are accomplished by arrangement of neighboring towns and hamlets. And this close-at-hand government is a trusted guardian of the community’s treasures—the farms, the two-room Sagaponack School, the Sagg General Store, and the Village Post Office, which shares a building with the general store.

SHINNECOCK HILLS

Here’s a story from before my time, about another incorporation attempt. It’s been handed down from one generation to another, and I cannot vouch for its truthfulness. But it sure is wonderful.

In the late 1800s, about 100 wealthy New Yorkers built mansions in the rolling hills of Shinnecock east of the canal. During this time, the villages of Southampton, Bridgehampton and East Hampton began to flourish with the influx of New York summer people arriving by railroad. Those in Shinnecock thought that maybe Shinnecock Hills, as it was called, should be called something that had the word “Hampton” in it. They met and agreed to try to change the name to Hampton Hills.

What they subsequently found, however, was that to change the name of a community they would need the majority of its year around citizens to vote the change.

There was another meeting. Most people were baffled about this.

“There is nobody here year-round,” one of them said. “We all just come out for the summer.”

“What about old man Terwilliger?” another said.

Herbert Terwilliger was the stationmaster for the Shinnecock Hills railroad station. He lived upstairs. He was who came downstairs to sell you tickets to the city from behind his little glass window. But he was also the Postmaster. Behind his glass window were all the post office boxes for the summer people. It was Terwilliger who put the letters in the boxes in the summertime. And it was Terwilliger who, all winter long, forwarded the mail to them in the city. He forwarded the mail! He was here!

“You’re right!” said another man. “Terwilliger is our year-’rounder. Let’s go see him.”

So they did.

About a dozen of the summer residents crowded into the waiting room that day and talked to Old Man Terwilliger about their proposition. They explained what they wanted to do. And they explained what needed to be done. Would he cast the necessary vote so that by one to nothing, they could report that a majority were in favor of changing the name of Shinnecock Hills to Hampton Hills?

Terwilliger thought about it for a moment. Then he spoke.

“Nope,” he said.

And that was that.