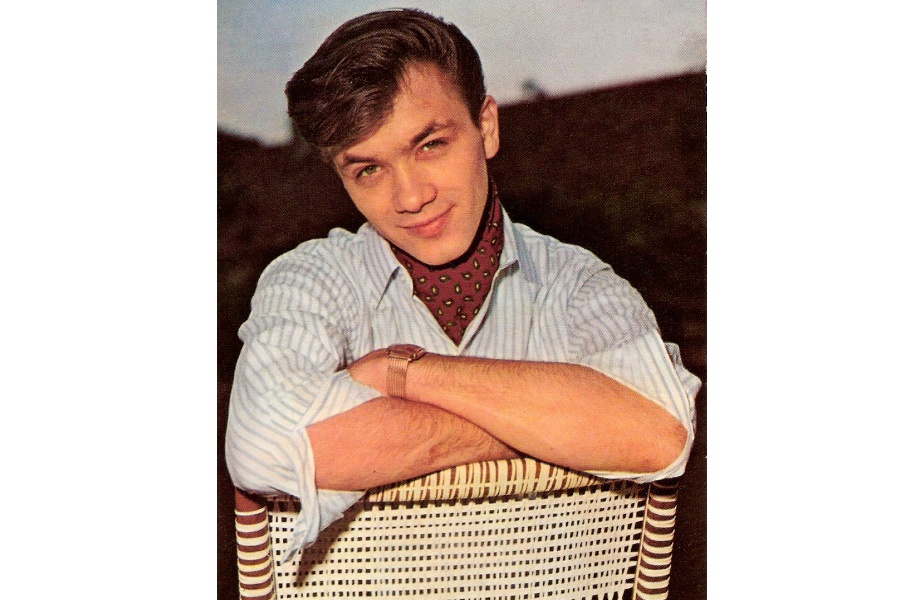

Neighbor: Gus Backus, Musician

Nashville Tennessee, mid-summer, 1974. I stepped into a sparsely furnished walkup apartment, four blocks off Music Row.

“Hi, I’m Gus, I’m looking to put together a band. I’ve got gigs lined up, good hotels, just need a group ready to go. You interested?”

He spoke with a German accent, pacing the room in bell-bottoms and clogs. No cowboy boots, Stetson hats or guitars in sight. This was different…

“Yes, sir,” I replied.

I’d arrived in Music City six months previously, a Telecaster-toting wannabe, up for anything that didn’t entail manual labor or blood bank donations…

“Here, listen to this, it’s the showcase song—‘Come Go With Me’—I was in the Del Vikings.”

“I know the song, Gus, everybody knows the song—you don’t have to play it.” I offered.

He placed a 45 on his portable phonograph, and I caught a gleam of gold as he lowered the needle. The familiar strains of the Doo-wop classic filled the room. Taking a closer look, I realized he was playing his presentation gold record, from 1957, given in recognition of a million units sold. With the Dot Records label, it looked a little worse for wear, and it sounded absolutely horrible! This relic belonged in a museum, framed on a wall, in a vault, anywhere but on a turntable. I said as much to Gus; he replied with a shrug,

“It’s all I’ve got—I had to leave Europe in a hurry.”

I thought to myself, “This guy’s a little crazy…but we could have a lot of fun…and if I get the gig he will never play that gold record again!”

Well, he was, we did, and a week later we made cassette copies from a nice clean LP. This was my introduction to the one and only rock ’n’ roll star born east of the Shinnecock Canal, an overlooked Hamptons treasure, and a soul survivor of international dimension.

Donald Edgar (Gus) Backus Jr. was born in Southampton on September 12, 1937, son of a potato farm foreman, and his wife, Georgia Rose. The Backuses lived in East Hampton, by the Hardscrabble Farm Dairy, which was located on Stephen Hands Path. They moved to Brooklyn a few years later, but Gus recalls climbing atop a really fragrant beached whale, and his mother saying he learned to swim in 1938, the year of the Great Hurricane.

As an adolescent, Gus fell in love with African-American music; jazz, blues, swing, and the “jump-blues” that was morphing into rock’n’roll and and rhythm & blues. Drafted by the Air Force in 1957, Gus was stationed in Pittsburgh, where he joined a multi-racial vocal group of fellow airmen, the Del Vikings. The group had recorded “Come Go With Me” shortly before, which went to #4 nationally, becoming one of the most beloved, well-known songs of the Rock Era. During Gus’s six-month tenure, the Del Vikings scored two more hits, “Whispering Bells” and “Cool Shake.” Gus sang lead on the latter, and claims to have written it as well. The credits on the record say otherwise, but it was commonplace for record execs to claim authorship and collect the royalties. (When asked if payola had anything to do with the success of “Come Go With Me” Gus snorted and said, “No, man. We didn’t have anything to payola with.”)

The Del Vikings appeared in Alan Freed’s Brooklyn Paramount concerts, on the Ed Sullivan variety television show, and had a cameo in the teen exploitation flick The Big Beat. Not bad for a 19-year-old with no musical training. Gus once ruefully recounted how the Del Vikings were granted leave to travel to Manhattan for the Sunday night Sullivan show, but had to be back on base Monday morning. As he was banging breakfast pots and pans around, his messmates complimented him on his previous night’s performance.

They were the only integrated ’50s group to score major hits in the era of Jim Crow and legal segregation. Before the Civil Rights Movement gained traction, before the Freedom Riders rolled through the South, before Dick Clark allowed interracial dancing on American Bandstand, these five Air Force guys were rocking and rolling in perfect harmony.

In July of 1957, Gus was shipped overseas to Wiesbaden, Germany, assigned to the Ramstein Air Force Hospital. An EKG technician, he claims to have had “all kinds of famous people on the deck,” including Egypt’s King Farouk and Marlene Dietrich; this may well be true—in post-war Germany, the US military medical facilities were the best available. He started another band, and performed at shows and dances in the Frankfurt area. When his Air Force hitch was up in ’59, Gus stayed in Germany—he’d married a local girl, and started a family. At the urging of his brother-in-law he began recording in German, taking the bus to Vienna for recording sessions, where he painstakingly sang translations of US hits, trying to shoehorn multi-syllabic German into something approximating the originals. When Gus makes this disclaimer at concerts today, “I want to apologize for many things that I have sung, I did not know what I was singing,” it’s only half in jest. His 1960 breakthrough hit was a cover of Johnny Horton’s “Running Bear” (“Brauner Bär und Weiße Taube”), and he racked up many more throughout the ’60s, in Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Denmark and Holland. He even had a #1 hit in Japan. “Goose Buckoos,” as his fans pronounced his name, developed into a consummate entertainer; versatile, engaging, and dynamically energetic.

Rock ’n’ roll is one of the few things Germans did not invent; it’s no surprise that a transplanted American, with talent, charm and a natural flair for the music would flourish in a society looking to “get footloose.” With apologies to Michael Jackson, Gus was often referred to in the ’60s as “The King of German Pop,” and his recording success created new opportunities. From ’59 through ’69, Gus appeared in 29 films, mostly light comedies. He made countless TV appearances, while concertizing throughout Europe. Life was good. Maybe too good.

Changing tastes, financial missteps, and marital discord sent Gus packing in ’74. He wound up in Nashville, where he had done some recording in the early ’60s. His record producer/arranger from the Del Vikings, Chuck Sagle, was living there at the time, managing an apartment building, if memory serves. (Everything changes, especially in the mercurial entertainment business.) It was a gallant attempt at reinvention, yet doomed from the start—Gus had been away too long. He’d lost the vital connection with the USA zeitgeist, his full-throttle style was out of synch with both Nashville Country and American Pop. He was Tom Jones-Vegas, a larger-than-life belter, when nuanced, subtler singers and bands ruled the roost. With an odd Mittel-European accent, lost-in-translation Teutonic humor, and the brash manner of a flamed-out yet stubbornly proud star, Gus was an exotic fish out of water; but never out of Budweiser.

I was a “New Del Viking” for about a year; we basically demolished the comfort zone of weary travelers looking for pleasant diversion in various Sheraton Hotels. At the time I didn’t fully appreciate how big a star Gus had been, how far he’d fallen. His moodiness and outbursts of frustration were annoying at times, but now I understand. He was a world-class singer/entertainer, accustomed to large orchestras and elegant venues, fronting a motley group of musical misfits and greenhorns (me), while singing his heart out to traveling salesmen and the cocktail waitresses that loved them.

We went our separate ways, remained friends, and in ’76 I was flattered when Gus asked for help with a recording session. He’d booked an all-star group, with D.J. Fontana on drums and Scotty Moore on guitar, from Elvis’s original band. Gus’s vocals were fine, but the record went nowhere. That was the last time I heard him sing, and we lost touch over the years. I often wondered about him, hoping he’d found some measure of satisfaction.

Some stories end well—Gus returned to Bavaria in the ’80s, remarried his second wife, Heidelore (it’s complicated), and is enjoying his golden years as a beloved elder statesman of German popular culture. He still performs, as “Papa Gus,” and he published his autobiography, Ich esse gar kein Sauerkraut—Die Autobiografie in 2011. I think the title translates as “I Eat No Sauerkraut.” He’s come a long way from the potato fields of East Hampton.

Colin Escott summed it up perfectly in liner notes to a Backus CD compilation: “Gus Backus’s story is among the most interesting in pop music. He has crossed more borders—musical, racial, and national—than most of us will ever dream of.”

Gus, this Bud’s for you—Prost!