The East Hampton Swans Are Having Family Issues

Every summer, the residents of East Hampton follow the activities of the two snowy white swans in Town Pond. It’s easy to do. The pond is right in the middle of town. Main Street borders its northern shore. James Lane borders it on the south. Anytime you leave town going west, you have to pass right by it. I do that almost every day.

Two years ago, in late March, the two swans arrived from their winter nesting grounds, wherever it was, and built a nest of twigs and leaves in the wetlands on the James Lane side. The female laid her eggs in it at the end of April and sat on it until June, when five tiny grey chicks were born. The male, who had until that time paddled gently around, keeping watch over his mate, bringing her food and otherwise taking care of her, now became seriously possessive. If you got out of your car to give them breadcrumbs now, he’d flap his wings and start toward you until got back in your car and drove off.

The village clerk often had to calm down upset motorists who just wanted to show their kids the swans up close but got treated this way. Just don’t go near them was the advice given. A little sign went up there to that effect for a while.

Eventually, the little cygnets grew and soon were either collected in a sort of gaggle in the water between mom and pop as they swam around or seen in a long line trailing behind as mom and pop proudly led the way. The male did calm down by the end of July. But in August, every few days there were fewer cygnets than there were before. People were concerned. They were not big enough to have flown off yet. What had happened? Environmentalists said that what did the babies in were the snapping turtles that live underwater in the pond. They’d come up from below and snag a baby cygnet by the leg and pull it down, they said. It was nature’s way. By August, it was just the two adults, alone. And they remained alone, often, when they swam around, with a space between them that had been where their babies had been earlier.

This year in late March, no swans at all came to Town Pond. They weren’t there in April or May either, and there was some belief that they would never return to the pond, even though for as long as anyone can remember, two snowy white mute swans have made their summer home there every year.

What was wrong?

In early July, one day, the two swans did appear in the pond one morning, swimming along with that space between them where, suddenly, there it was, a half-grown grey baby cygnet. Experts in the community said at the time that the two swans had been in the area all along, but had built their nest this summer in Hook Pond, which is down a path and through a woods about 100 yards away. Incredibly, one morning, the two adults and their lone surviving cygnet had waddled up the path to spend the day amidst the hustle and bustle of Town Pond. They had returned to Hook Pond around dusk, but the next day they were back. Apparently they liked all the traffic there. They also apparently liked that people would pull over and park and feed them breadcrumbs from time to time.

This situation remained in place for almost a month. But then, one day in early August, once again, the adults appeared without the cygnet between them. This cygnet, again, was not old enough yet to have flown off. But she was gone and once again the male and female were alone.

And then, two weeks ago, this situation took still another turn. As I drove along Main Street that day, I saw that indeed the two adults were in the pond but—was it possible?—there was a small white creature swimming along between them. I had driven past the pond before I could see exactly what this was, but of course I thought somehow, it was the cygnet.

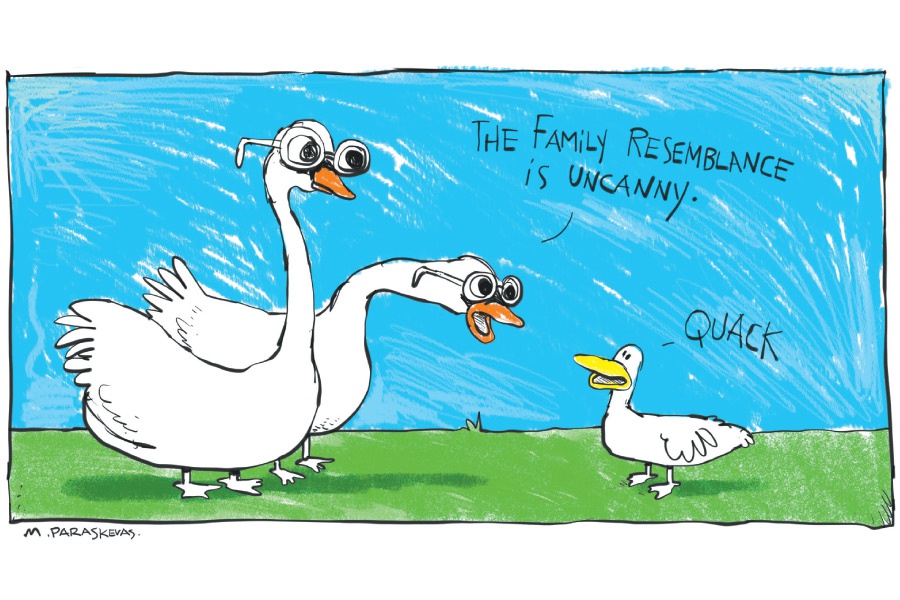

Later in the day, coming back from Southampton, I saw them again, the two proud parents with the little white creature swimming between them—and this time as I drove by I got a good look at it. It was a white duck with a bright yellow beak. We have ducks in the pond, always have. But they are all mallards, grey and green creatures, with nowhere near the majesty of the great swans. And now there was this. Someone’s pet? An albino mallard? It was there a second day, then a third and a fourth.

Several weeks ago, I read an article about how scientists in the Midwest had saved the Whooping Cranes. At one point about 20 years ago, there were fewer than 500 Whooping Cranes on the planet. These 500, for their own protection, had been rounded up and placed in a great pastureland where they could be monitored, something fairly difficult because the Whooping Cranes were shy of humans and would run off if the humans appeared.

But the scientists soon found that if they dressed up in white Whooping Crane suits, the cranes accepted them. They’d even follow them. In the autumn, the scientists then had a further success. The time had come for the Whooping Cranes to fly south. A place had been set aside for them in Florida. But how could they get them there? The answer, as it turned out, was ultralights.

Ultralights, these very lightweight personal-sized aircraft about 10 feet long with wingspans about the same, were brought into where the Whooping Cranes were and then driven around on the ground. The cranes, curious, ran after them. They began following them around. Then, after the cranes were fully acclimatized to the ultralights, the scientists tried something else. They had the pilots of the ultralights bump them along down a field and up into the air. Sure enough, the Whooping Cranes took off too and arranged themselves behind the ultralights, and in this way, after numerous trials and errors, the ultralights took the Whooping Cranes to their winter grounds in Florida.

Now, this is a well-known story. It all happened about 20 years ago. And today there are thousands of Whooping Cranes, and they go south by themselves without the aid of the ultralights.

The new story about the Whooping Cranes is this. Beginning about two years ago, many flocks of Whooping Cranes were seen to be going more than 30 miles off course when flying to Florida. They’d still get there, but they would be late. What to do? The scientists studied the situation and found that in some cases, the flocks that were heading off course would often get brought back on course by elders in the community, the oldest Whooping Cranes. The younger ones, in flight, would seek them out, instinctively, and urge them to take the lead and they would. The scientists were now proposing, in the paper I read, that this was a proof that in some species anyway, the wisdom of the elders was a very important thing.

My thinking about our two white swans is that, like the Whooping Cranes, they may have turned to this strange snowy white duck in the belief that it could become a baby swan. Perhaps it is a case of bad eyesight. Perhaps it is a case of wishful thinking. We may never know. In any case, this past Monday, the two swans were seen swimming alone once again, that special space between them again vacant.

My guess is that the white duck, this full grown white duck, had, after a fashion, had enough of being taken care of by a couple of swans. And off it flew.