Who's Here: Tate's Bake Shop Owner Kathleen King

When the founder of Tate’s Bake Shop offers you something right out of the oven at her Southampton dessert mecca, the prudent move is not to worry about calories or waistlines. Carpe crustulem. Seize the cookie. Or something like that.

Treat in-hand, you follow Kathleen King through the bake shop’s kitchen and up to her office on the second-floor of the light-green building on North Sea Road. Here, only the floorboards and an impressive willpower separate her from the butter-and-flour-filled factory below where some of the most famous cookies in America are created. King herself decides not to have anything to eat. It’s like Willy Wonka passing on an Everlasting Gobstopper, you think. You hear stories about people in, say, ice cream parlors who wind up hating ice cream, but that’s not at all the case with King. Her feelings for the confection that put her on the map are as strong as ever.

“It’s been almost 35 years in business, and I was baking 10 years prior, and my favorite cookie is still chocolate chip,” King admits, sitting at her desk. “I’m never going to get tired of them. If I ever hate them, it’s because I have to work too hard, or I ate too many and I don’t feel good—but it’s nothing that they did!” A smirk spreads into a full-fledged smile. “And then I recover and love them the next day.”

She pauses, considers this relationship with her cookies. “Sounds like marriage.”

If ever there was a human who found a soul mate’s bond with a baked good, here she is. For all the sweet treats she creates, though, King exudes a no-nonsense get-it-done toughness that is equal parts farmer and Forbes. The farmer part is in her genes, having been born in Southampton and raised on North Sea Farms. The Forbes part, in actuality, was born there too.

“When I was 11, my dad said I needed to bake cookies to sell at the farm stand, because I was old enough to buy my own clothes for school. My sister and her friend baked cookies sometimes, and they baked brownies, and bread—they weren’t focused,” she says with a sly grin. “And then when they got older, like 13-14, they wanted to get a real job, and they wanted to work in an ice cream parlor because they could meet boys. So I started baking and selling, and my sister and her friend went off to the ice cream parlor and did their thing, and then I kept baking and selling cookies.”

Tweaking and refining the recipe of the back of the Nestle’s package to make it her own, King created a product popular enough to buy those clothes, and then some. But she had dreams of being a veterinarian, not a baker, when she got into high school. “But I was smart enough to know I wasn’t smart enough. And so when I graduated college I went back to the farm, and I was making cookies to sell that summer and my mother said, What are you going to do? And I said I don’t know.” Mom told her about a bakery for rent right in Southampton Village, King took it, “and that was my first job.”

And her last. Bakeries in her spot had failed twice before, but King is not one to let such omens dissuade her. Within a year a New York Times article had spread the word about King’s creations to the NYC folks who were heading east in increasing numbers, and over the next two decades she built Kathleen’s Bake Shop into a Southampton institution.

A few years later, her mother, again with an eye on local real estate, told King that there was a building up the road for sale, and although she hadn’t been planning to move just then, it couldn’t hurt to inquire. “The gentleman was willing to sell it to me, and I had $40,000 and I needed a $50,000 down payment,” King recalls. “In figuring out where I was going to get that extra 10 to go with my 40, I didn’t know anybody with any money. My parents didn’t have any money. But there was a woman in town, she lived on Hill Street, her name was Rose de Rose. Lovely woman, lived by herself, and my dad used to help her from time to time. She loved to raise chickens, so he would help her with things like that. When she died, she left him $10,000. And she died when I was looking for $10,000.” This last part is said almost in a whisper, as if uttering it too loud will undo the twist of fate. “So I borrowed it from my dad, made more cookies and paid him back.”

Cakes and pies and scones and awards and accolades piled up, but a partnership in the late 1990s turned into something out of a bad movie, and King wound up not only barred from the bakery that had her name hanging out front, but eventually lost the name Kathleen’s Bake Shop and wound up with $200,000 in company debt when all was said and done in court. She also got a glimpse of the Hamptons many people never see.

For all its glitz and glamour, Southampton is woven with the thread of small-town America, and the locals who knew Kathleen supported her. Amid accusations and ugly times, they were there. “That was kind of a shock to me,” King admits, looking back. “I knew that people liked the store, but I didn’t know they loved the store like that.”

Luckily, King owned the building that housed that beloved store. A remortgage and a name change later, Tate’s Bake Shop was in business. The name Tate’s was for her father. The rest was King.

“It was very warm and wonderful, and most everybody was really nice and supportive. Someone said to me, ‘Southampton isn’t like it used to be,’ and I said, ‘True, but that underbelly is still here.’ This community really does still rally to take care of their own. It makes this place so unique. Even in the 1960s when I was growing up, my dad used to tell me, ‘Kathleen, this is not the real world.’ It always seems when there’s a worldly crisis, we are the last to fall and the first to get up. And it’s over and over and over. It’s fascinating. I wonder, do we live in this bubble? And I think, I like to know what’s going on in the world, but I’ll stay in our bubble.”

It’s where King has found financial success, to be sure, but also solace. It’s in the outdoors she so loves, the kayaking and hiking. And just as the locals supported her, King gets behind the parts of local living that mean the most to her. Two particular passions are i-tri, a program which helps East End girls build self-esteem and life skills through triathlon training—“I like to support that, because those girls are growing up in our community, so you change those girls, you change our community”—and the Peconic Land Trust.

“I come from a farm upbringing, and they help preserve farm land for agriculture—one day we don’t want to drive around and there’s no farm stands and no open fields. That’s part of our history and who we are,” King says. “Once we lose all that, we’re not going to be anything. Yes, we have the beautiful ocean beaches, and thank god that’s been managed to the point where there are no hotels and all that horror. But without the open space and back roads where you can ride your bike—I still live here, so I can still find those places, but it’s becoming harder and harder—our bubble will pop.”

As she speaks, there’s a sense of wonder that embodies what many fulltime East Enders feel but may find hard to articulate. “I walk on the ocean beach all year long, take my dog. I’m 54, and I’ll still be there with a friend and I’ll look around and say, This is where we live. This is where we live. I never get tired of that. In the winter when it gets really cold we hike in the woods, where it’s warmer. In the summer, my favorite restaurant is a beach fire and food that friends all bring, or lobster rolls from Canal Café, and the sun’s setting, the fire’s going and that’s just the best.

“I love all the seasons out here,” she continues. “I love the fact that it changes. I love the dead quiet and the fact that it allows me to slow down. I love the anticipation of spring and the summer’s coming and the people and the crowds,” she says. “And I always find with the seasons comes a sense of renewing in my own self, because it just brings it on naturally. If it stayed one way, I think I’d stay one way.”

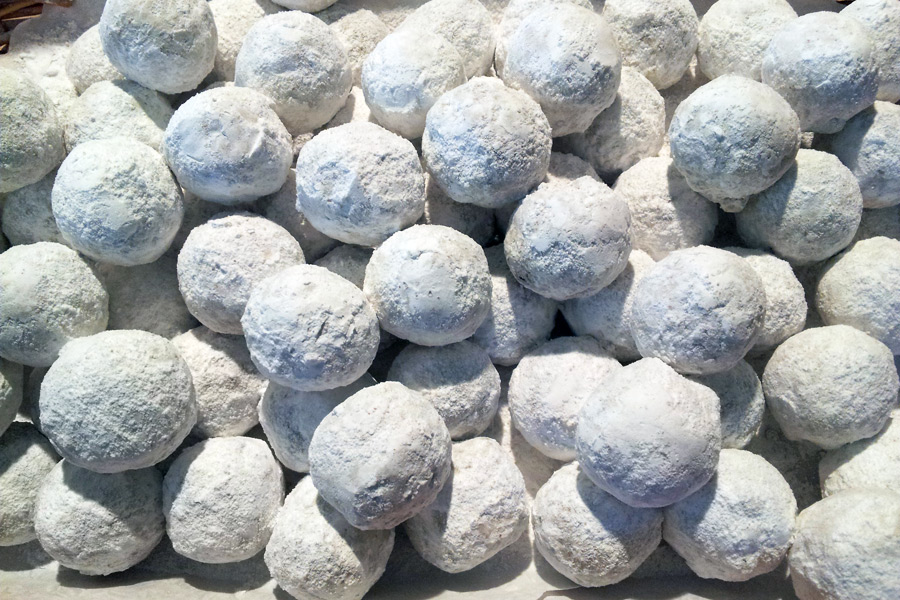

Which seems impossible. Part of King’s makeup is always pushing ahead, seeing what else can be done, trying the improbable. Had she stayed one way, she’d be baking only small batches in Southampton, not owning a 45,000 square-foot facility in East Moriches that turns out some 2 million cookies a week, which are hand-packed and sent off to nearly all 50 states, Canada, the Caribbean, Hong Kong. In 2012, Consumer Reports named her originals the Best Chocolate Chip Cookies in America. Her Whole Wheat Dark Chocolate Chip Cookies took top honors at the Fancy Food Show in New York City this past year. Her Gluten Free Chocolate Chip Cookies have reduced gluten-intolerant people who thought they’d never have another edible treat to tears.

“I can’t say that my vision was this big,” King admits. “I grew up on a farm, so I had a simple upbringing. For me it was just about being able to wake up happy and cover my ass. That’s my definition of success. If I could get an apartment, get a house—nothing was grandiose. My real fantasy was to be the number one cookie in America. It didn’t necessarily mean I’d be making 2 million cookies a week, but my pride factor said I want to be the best.”

That pride remains evident, and extremely personal. King still tries every new recipe at home first, as she did decades ago, before bringing it to the shop. But that shop no longer rules her days at the expense of all else.

“I have an advantage of living my life kind of twice,” she says. “With Kathleen’s Bake Shop, that was my baby. I was a workaholic, and I worked my whole youth away. The only thing I grieved when I lost everything—everything as far as the business went—was my youth. Because I can’t get that back. When I opened Tate’s, I said ‘I will not do that again.’ Life is really short, and it goes really fast, even if you live really long. I had given enough up for the company, and in the big picture, I make cookies. It’s not life and death.”

Fans might beg to differ.