Should We Preserve the Art Studios of James Brooks and Charlotte Park?

Beginning around 1949, approximately 20 young New York City artists and sculptors met regularly at an 8th Street apartment they called “The Club,” and, after some discussions, agreed to migrate en masse to East Hampton to establish an art colony here. There were many reasons for the move. Post-war housing was one of them. There were not enough apartments to accommodate returning GIs at the time. There was also the tumult of the city versus the peace and quiet of the Hamptons.

The artists who came here, mostly men but some women, worked in many formats and styles, but what they are most known for is that their arrival made the Springs section of this town a hub for Abstract Expressionism, a new way of looking at things through painting that soon became acknowledged as a new art movement. Indeed, for a time, 50 years or more, this town was considered a major working art capital of the world.

The news that the home and studios of James Brooks and his wife, the painter Charlotte Park, have been left abandoned since her death, in the woods in Springs, has sparked some interest in saving what’s left of this historically important community. I say what is left because, for some reason, the Town of East Hampton placed such difficult restrictions on the creation of separate art studios, including that they be demolished after six months if not in use, that the importance of this community, particularly during the half-century it was in its heyday, may soon be gone forever, without a trace (with the single exception of the art studio and home of Jackson Pollock and his wife, Lee Krasner).

But let us begin with James Brooks’s studio that’s in the news up in Springs. Brooks, an important member of this community, became famous for his grand mural in the rotunda of the Marine Air Terminal at LaGuardia Airport, completed in 1940. It was 12 feet high and 237 feet long along the walls, coming around to meet itself. It was painted over for a time. It is today, back and fully restored.

Brooks was born in Missouri and raised in Texas and Colorado, the son of a traveling salesman, and at 20 moved to New York City just prior to the Depression and became part of that city’s art scene. He did that mural, and numerous others, for the WPA (Works Project Administration), the government art project.

During the Second World War, he was a soldier attached to the OSS, the American overseas intelligence agency, based in Cairo. Through some kind of crack in the military system, his assignment there, along with the assignments of numerous other artists, was to paint scenes of American war equipment and soldiers behind the lines. It was actually a military order. Brooks, in an interview he gave in the 1960s that’s now in the Archives of American Art, remembered it as, “You’re free to carry a camera and photograph secret installations, to enter such and such and such and such. So we had entry everywhere, [to] paint with the romanticism of a Delacroix, with the savagery of a Goya, or, best of all, follow your own inevitable star.”

That must have turned a few heads amongst the colonels.

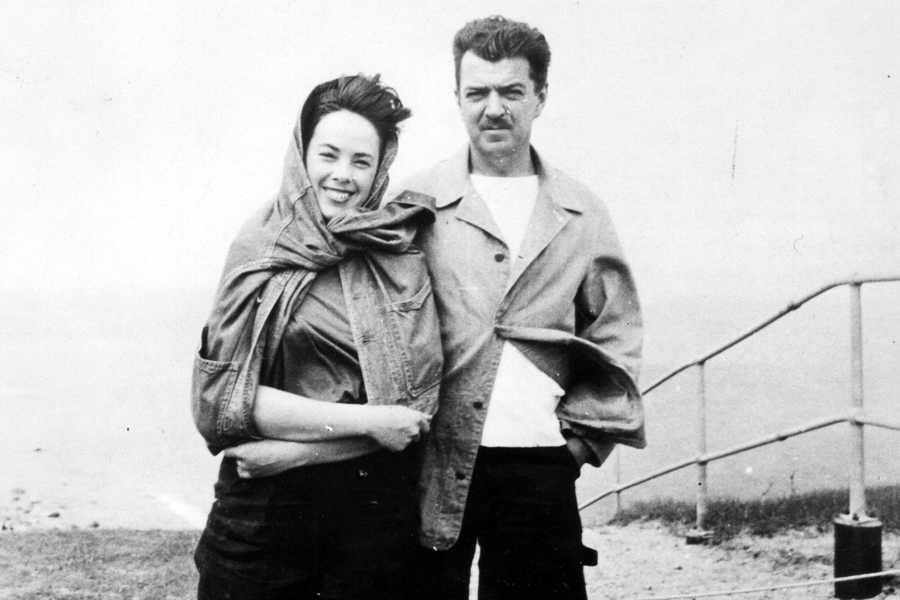

It was in Washington, D.C. that he met another artist, Charlotte Park, 12 years his junior, also working at the OSS. When he returned to New York City, he returned with her, and they were soon married and were to live and work together for more than the next 50 years.

They moved to Montauk in 1949, two years after they married, and settled in a small fisherman’s house and outbuilding on a cliff at Fort Pond near the Navy dock. The outbuilding, which became their shared studio, faced north, as it faced the water, taking advantage of the northern light so favored by painters.

In 1954, Hurricane Carol came crashing through Montauk with a near-direct hit, and it blew the studio right over the edge of the cliff and down to the beach, where the building collapsed. Everything inside was lost—paintings, canvases, brushes and books—and all that remained in good condition was the front door, which friends hauled back up and which has been saved to this day.

The Brookses bought 11 acres of land on Neck Path in Springs after that hurricane. They therefore joined, up close and personal, with the great clan of painters and sculptors who had come to the Springs community. And a few years later, they prevailed upon a local man named Jeff Potter, who had a barge and towboat, to gather up the remains of their studio and move it to the new property in Springs, where it would be rebuilt next to the new house he constructed there. It remained there, as part of the Brooks-Park compound, for the next half-century, with the two painters active, making their work, Brooks in his old rebuilt studio and Park in a new one.

James Brooks died in 1992 at the age of 85. Charlotte Park died in 2010 at the age of 92. They had no children. But their heirs sold the 11-acre property to the Town of East Hampton for $1.1 million as part of the land preservation program. The land would be saved, presumably, never to be built upon.

For the last three years, the house and the two studios have been slated for removal. But those who have gone into that woods to see them in their already dilapidated, picked-over state are thinking otherwise. The paint cans are still on the shelves. There are racks of frames for canvases. There are books. And now there’s a movement afoot to save the buildings, not just because they were the studios of two famous artists whose works are collected at the Met and MOMA and other places, but because the rest of the now-abandoned studios in that community are slowly being abandoned, too.

The reason? The Town of East Hampton, years ago, first in 1985 and then in a revision in 2006, took the position that artist studios should be torn down if not in use for more than six months.

One might think that East Hampton would celebrate the lives of these great artists who caused such a stir—the likes of Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, John Little, Philip Pavia, Franz Kline and many, many more. But in 1985, with the wave of Abstract Expressionists beginning to recede, the town became more concerned with “regulating” the studios. What if the new owners of homes with these studios on the property wanted to rent them out? Two families living on one lot? It was not legal to do that. It still isn’t legal, though these days the town has been accused by some of turning the other way when they see this activity. We are living in different times.

An “artist studio,” in 1985, was therefore described in the town code. It’s a place where a single artist did his work. This artist could do that. He could not, however, sell work from his studio, sleep in it, cook in it or go to the bathroom in it. Having a bathroom in an artist’s studio was illegal. Having a stove, too. Still is.

Also, there can only be one artist. And when his or her day is done, a new artist has to be found within six months or the place gets torn down. And the new artist has to have “bona fides.” There’s a form to be filled out. He or she has to have work sold to museums or galleries, has to have had shows, has to be known for what they do. I’m not making this up. The town code even creates legal “inspectors” for the premises. If you had an artist studio and you wanted to get this permit, you had to agree to allow an inspector to come and inspect at least once a year, and then without much notice to do so. There should not be time to take out a bed, remove a toilet, unbuild a refrigerator. (Coffee makers and microwaves were an exception.) And that was that.

Many new artists have moved into the Springs to follow in the Abstract Expressionists’ footsteps and to enjoy the beautiful northern light, which many say reminds them of Holland or the South of France when it filters into their studios. We certainly do have artists today whose reputations rival those of their predecessors. We have Julian Schnabel, Cindy Sherman, Donald Sultan and Barbara Kruger among many others.

The world has turned many times since those heady days half a century ago. And art studios were not usually made of the best building materials. But let us get to it, and save the legend as best we can.