Throw It Out: Personal Papers, Old Clothes and Love Letters

There was news last week in Southampton about the problems we face here in throwing things out.

You know those bins that say not-for-profit on them where you can throw out clothes to hopefully have them used by those less fortunate? Turns out they are not always on the up and up.

Turns out there have been bad people who have gone to some of the up-and-up bins, covered up the names of the nonprofit on the side and replaced them with fake names and then moved the bins—so these bad people can come around and collect the clothes themselves so they can re-sell them.

Turns out there have been bad people who follow around a truck from a charity that’s on a weekly route to collect old clothes that have been put in bags in front of people’s homes. The following week, the charity truck goes out and there are no clothes. The bad people, having memorized the route, have been there earlier in the day.

Turns out there are also some bins run by for-profit companies, who sell the clothing that people have dropped inside just assuming it was going to charity.

As a result of this, Southampton Town is considering passing into law a new ordinance that would require all charitable clothing bin people to go to the town, show they have a 501(c)(3) registration and are approved to do charity work, and get a sticker to put on the bin. Next time you go out to throw out unwanted clothes, look for the sticker.

As it happens, all the towns and villages in the Hamptons have had their problems with people throwing things out.

Early on, you’d throw out things by taking them out to the garbage can, throwing them in, hauling the can to the dump and shaking out the contents onto the big pile. And that was that.

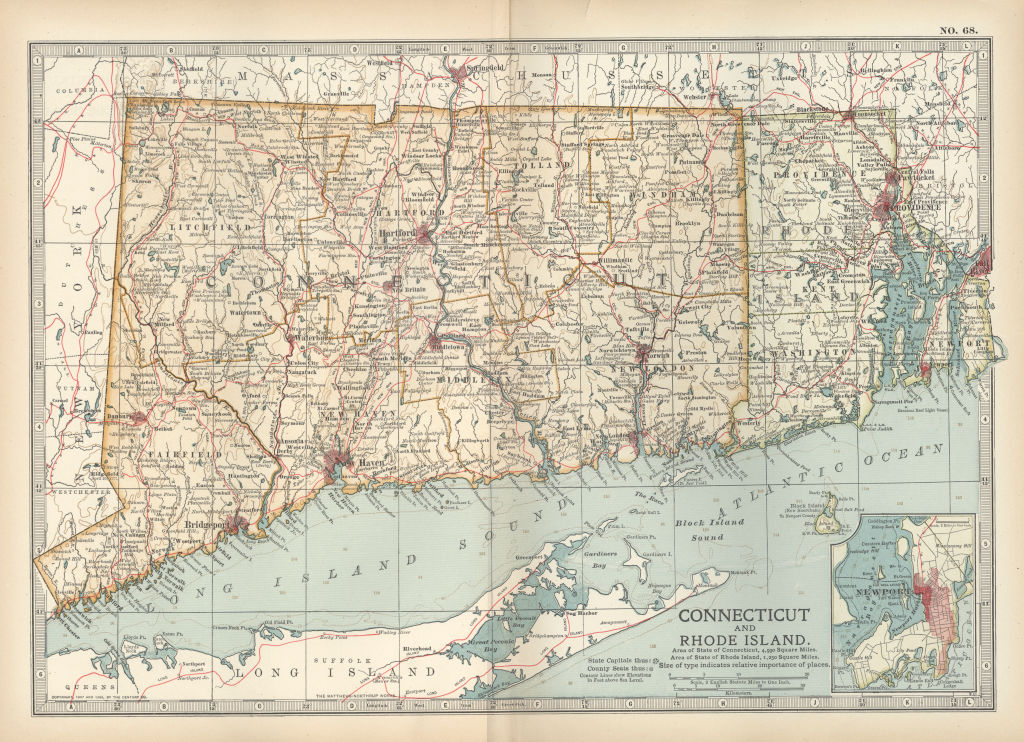

But then times changed. Although not completely. Today almost every town and village on Long Island has a municipal pickup service. A town vehicle comes up to your driveway and takes stuff away. It’s paid for by your taxes. But not in the Hamptons. Here, we still don’t have municipal garbage pick-up. We also don’t have paid fire departments. The volunteers put out fires just fine, thank you. And as for garbage, old clothes and furniture, fend for yourself. Take your garbage to the transfer center, put your old clothes in the bins, break up old furniture and pay a fee to dispose of it at the transfer center. The dump is closed.

I remember the week that the dump closed. Before that week, you could drive in almost any time to leave your garbage. It was especially convenient for second-home owners. They’d come out with the kids to their homes for the weekend, then on Sunday throw the trash into the trunk and drop it all off at the dump on the way back to the city. It worked perfectly. You didn’t want to leave trash at the house for the raccoons. Just take it to the dump as you leave.

What they found, that first Sunday, was a big steel gate locked up across the entrance to the dump on Springs-Fireplace Road. It was now the transfer center, open Monday to Friday 9 to 5. The summer-home owners had a choice. They could keep their smelly garbage in the car and drive off with it. Or they could pile it up against the steel gate. On Monday at 9, the town found hundreds of bags of garbage piled against the gate.

Can’t have this, they realized. The next Sunday, they had police officers with pistols stationed at the former dump. The people would drive up, see the cops, back away and continue on with their garbage. Worked fine for the town. Not so fine for the second-home owners.

You’ve probably guessed what the second-home owners with the kids whining in the back seat now did. They weren’t much farther along from the gate when the adults in the front began to be on the lookout for a retail business that had a dumpster on the side or around the back. You just pulled in, opened the top, and dropped in your garbage. End of story. Took no more than a minute. And you’d get away clean.

During the next month, I began to get complaints from merchants here and there along the way about their coming to work on a Monday morning to find garbage that wasn’t theirs in the dumpster. I told them to call the police.

One day, I got a call from the owner of an antique shop on the highway in Wainscott.

“Guess what I got in the garbage?” he said.

“What?”

“You’ve got to come down and see.”

I went. What I saw was the tax return of a second-home owner who worked at Lehman Brothers in Manhattan. He made quite a tidy sum of money that year. All you had to do was brush off the ketchup.

I photographed it, took it with me with the permission of the antique dealer, ran a picture of the front page of it in the paper, with his name, address in Manhattan and total taxable income.

“I have your tax return,” I wrote. “Hope it’s not causing you any inconvenience. Come and get it.” I also wrote where it had been found. He never came to get it. But he did stop putting his garbage into the antique dealer’s dumpster.

But that wasn’t the end of it. About a month later, I was driving along Hedges Lane in Sagaponack and came upon an enormous white sign that had been strung between a barn and a telephone pole at the Osborne Farm. You didn’t even have to drive into their gravel parking area to read it. It was on four sewn-together bed sheets flapping up there, and had the name of this guy in big letters, asking him not to leave his garbage in their bin either. I photographed that and put it in the paper.

On another occasion I got a call from the head of the recycling center up in North Sea that had formerly been the town dump. He invited me up, telling me I would not be disappointed, and I went.

What I found was a makeshift “house,” entirely made of dump items. There were pieces of roofs, windows, sofas, lamps, a TV, a coffee table and so forth in one room, and then there was a bedroom and bathroom adjacent, fully equipped. The whole thing was see-through. If they had shingled it you could move in. Well, of course you wouldn’t want to. So I wrote a story about that.

The following year, that same transfer center director called to tell me I ought to get in my car and drive down Wainscott Farm Road, and “where it crosses the tracks, just stay straight and go about a hundred yards on the dirt path and look to your right. You will not be disappointed.”

What I found there was an enormous pile in the woods that consisted entirely of the contents of the office of a United States congressman. There were filing cabinets, office chairs, bookshelves, folders, framed photographs, secret “for your eyes only” files.

I got down on my hands and knees and began to shuffle through all of it. I found file drawers filled with folders of local people applying to West Point. I found blueprints of nuclear plants. I found top secret briefing papers. All if it was from an eight-year period about 15 years earlier, when our elected congressman Stuyvesant Wainwright II served his four terms in Congress down in Washington.

I was there over an hour. Then I heard the sounds of buzzing motorcycles. The sound got louder and louder. They were coming to arrest me. That turned out to be a 10-year-old boy on a dirt bike who came bursting out of the woods, waved and smiled, circled around the pile once and then drove on down another path and away. I left shortly after that. And I wrote a story about that find, illustrating it with a drawing showing an architectural plan for a nuclear rod disposal pod.

I published an account of that find in my memoir In the Hamptons. And soon after that, I found out from friends and family what all that stuff was doing there. I was also told that the congressman loved the story.

The Wainwrights owned a big house in the Georgica Association. But then they went through a divorce. Mrs. Wainwright got the house in Georgica, but it bothered her that the entire contents of her ex-husband’s Washington office had been moved and set up in the basement of the house. She asked him to move it out. He didn’t. She asked him again. He still didn’t.

And so, without his knowledge, she hired a man with a big truck to take the contents of this office “away.” He very likely promised her he’d take it to the dump. But now, of course, there was no dump, there was only the transfer recycling center where the dump once was, and you had to pay a fee to drop stuff off.

How much cheaper would it be just to drop it in the woods? Who would know?

So that’s what happened.

Volunteer firemen, masquerading clothing bins, recycling centers, town dumps and income tax returns. It’s all part of the Hamptons. So watch out.