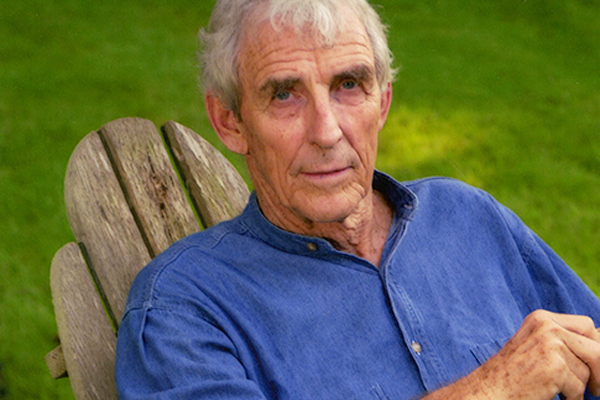

'Men's Lives' Author Peter Matthiessen Dies at 86

Peter Matthiessen, the tall, gentle presence who for more than half a century made Sagaponack his home, has died at the age of 86.

Matthiessen made his mark on the world in many fields, most notably literature, where two of his many books won a total of three National Book Awards, two for nonfiction and one for fiction. He also wrote Men’s Lives, which drew upon the three years in the mid-1950s when he was a commercial fisherman, working with the local Bonackers in these parts, haul-seining for bass and bluefish from pickup trucks and boats along the ocean beaches here.

Matthiessen grew up among the wealthy set of Manhattan in the 1930s. One of his best friends was the late George Plimpton, with whom, in Paris in the 1950s, he and others founded The Paris Review. The two grew up in the same Fifth Avenue building and went to St. Bernard’s School together; Matthiessen eventually went off to Yale, while Plimpton attended Harvard. Both rebelled from their backgrounds as young men. Both became authors and both traveled widely, Plimpton largely among kings and queens and other royalty, Matthiessen largely among adventurers and explorers. Matthiessen came to celebrate the natural world.

Matthiessen joined the U.S. Navy at the tail end of World War II and at 18 served at Pearl Harbor. After the war he went to Yale, where he wrote a short story, “Sadie,” which won a prestigious prize given by The Atlantic magazine. After graduation in 1950, inspired by the prize and The Atlantic’s accepting a second story, he hired an agent, Bernice Baumgarten, and gave her the first few chapters to a novel, and she sent it around.

“I waited by the post office for praise to roll in, calls from Hollywood, everything,” Matthiessen said in an interview with Kay Bonetti of The Missouri Review years later. The letter soon arrived. “Dear Peter, James Fenimore Cooper wrote this 150 years ago, only he wrote it better. Yours, Bernice.”

Many prominent American writers went to live in Paris after the war. They included Irwin Shaw, Terry Southern, James Baldwin, James Jones, William Styron and others. Matthiessen went, too, to write a novel but also secretly as an agent for the CIA. He needed a job to support himself while writing. With the CIA, he reported on the activities of certain Americans in that community.

Matthiessen later said being a CIA agent was the only adventure he ever regretted. He was young, he said. But the fact was, many Yalies joined that organization after the war.

Matthiessen married Patsy Southgate, an American he had met in Paris while they were both undergraduates studying at the Sorbonne. Then, returning to Paris, he talked to author Harold Humes and others about starting a literary magazine. Matthiessen would be publisher, but early on he felt Humes, though brilliant, was too erratic to be the editor. So he turned to George Plimpton, his old friend from America, at that time studying in London, who became the first editor of The Paris Review in 1953. (Plimpton remained its editor until his death in 2003.)

Matthiessen left the CIA shortly thereafter, but many years later had to tell Plimpton that The Paris Review was founded as a “cover” for his day job with the CIA—something that, by all accounts, made Plimpton very angry for a while.

Matthiessen and Southgate returned to America and rented a house in Sag Harbor. Matthiessen continued his writing, but it wasn’t bringing in much money. So he started to run a charter boat that took people deep-sea fishing out of Montauk. In addition, he became a commercial fisherman, working with the Bonackers fishing for sea bass and bluefish out of the surf in Bridgehampton. A decade later, Matthiessen bought six acres in Sagaponack and made that his home. He would live there the rest of his life.

There are locals today who fondly remember Matthiessen in his years as a commercial fisherman. Often, he would be away traveling to exotic places such as Peru, Tierra del Fuego, the Amazon or Tanzania. But he’d always come back. John White, a local farmer, remembers a day when he was 10 years old and his dad and their friends caught an exotic, brightly colored fish in their net with all the bluefish. Matthiessen was not with them. But they figured he would know what it was, so they brought it to him. He had no idea either.

Another time, according to White, some exotic pet that Matthiessen had brought back from a trip to the outback of Australia—a dingo or something—attacked some of White’s pet ducks.

“He was so apologetic,” White said, “that I couldn’t be mad at him. He was really such a nice guy.”

Matthiessen often said his time with the Hamptons locals was among the happiest in his life.

In 1956, Matthiessen and Southgate divorced. In 1963, he married writer Deborah Love, who was a member of the newly blossoming counterculture. They both experimented with LSD and other drugs and subsequently, Love became a Zen Buddhist. Soon thereafter, Matthiessen followed.

Love died from cancer in early 1972, and it had a great effect on Matthiessen. He went back to his traveling in earnest and wrote prolifically, creating some of what his critics consider his greatest work.

He wrote Far Tortuga in 1975, a novel about a ship captain out of Grand Cayman searching for turtles in the Caribbean. In 1978, five years after traveling on a quest in the Himalayas to find, among other things, the endangered snow leopard, he wrote The Snow Leopard, which won the National Book Award for “Contemporary Thought” in 1979 and, in 1980, for General Nonfiction. Altogether he wrote more than 30 books, and included among them was 1986’s Men’s Lives: The Surfmen and Baymen of the South Fork.

But Zen Buddhism, the art of quieting your mind so you can live in the present, sitting silently with friends cross-legged on a zafu, meditating for hours on end, became, along with his writing and his adventures, Matthiessen’s main passion.

Some will recall the zendo, the meditation room that Matthiessen created on his property, accessible from Bridge Lane in Sagaponack, where many of his friends and he would assemble for tea and meditation, sitting for hours and hours. It was, in fact, open to all comers.

A particular story from that era stands out in my mind. Matthiessen drove an old sedan. He was, of course, an environmentalist. No sense recycling a car that was perfectly good. One morning he woke up to find he had parked the car but had never turned the engine off. It had been on all night, and still had not run out of gas. That he had done that both appalled and amused Matthiessen no end.

Matthiessen married Tanzanian-born Maria Eckhart in 1980. In 2008, he received still another National Book Award, for Fiction, for Shadow Country, a retelling of his earlier works known as the Watson Trilogy.

Matthiessen’s last book, In Paradise, a fictional work about a group coming to a former Nazi death camp for a meditative retreat, was by coincidence published only a few days after his death from leukemia last Saturday at a hospital near his home here. He is survived by a son, Lucas, and daughter, Sara, from his marriage to Patsy Southgate; a daughter and son, Rue and Alex, from his second marriage, to Deborah Love; two stepdaughters and six grandchildren.