Shark Cage in the Water: Face to Face with Montauk’s Bad Fish

It’s true what Quint, Robert Shaw’s grizzled sea captain says in the first Jaws film.

“Sometimes that shark, he looks right into you. Right into your eyes,” the endlessly quotable and doomed shark hunter recalls dolefully. “You know the thing about a shark, he’s got… lifeless eyes, black eyes, like a doll’s eye.”

I try to heed each of the two large blue sharks circling the cage, but as one of these impossibly beautiful and perfect predators passes just inches from my face, I am hypnotized enough to momentarily lose track of its feeding partner. I could swear the bigger one, nearly 8-foot, is clocking me instead of the bait dangling before it. Quint was right, the eyes are indeed black, hollow and devoid of the dancing flame of life that connects us with other men, women and the animals we often keep.

The candle has been snuffed out—or never lit—and only charcoal and ash remain. This shark is truly an animal, a creature of pure instinct and function, virtually unchanged for millions of years. And it’s so close I can make out every pore and scratch on its elongated face.

This is what I came to see—one of man’s most feared creatures, a perceived monster, in its own murky blue and green environment. Now where did the other one go?

Hours before meeting this enigmatic “bad fish,” as Quint describes it, I had doubts we’d even see a dogfish, let alone a beast that surpasses the length of my 6-foot-3-inch frame.

Operating on four hours of sleep, I arrived at Westlake Marina about 10 minutes late on a rainy Thursday morning. The Sea Turtle—a 36-foot BHM downeast-style lobster boat outfitted for wreck and shark cage diving expeditions—had six dark figures gathered atop its deck, silhouettes in the wet, gray morning.

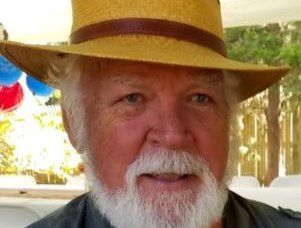

Captain Chuck Wade, his first mate, Bella Ornaf, and Sea Turtle Dive Charters’ guests welcome me aboard and we set off posthaste—but not before I’m told to eat or toss the two bananas I’ve packed for lunch. “They’re bad luck,” the superstitious captain says quite seriously, watching me stuff my face with fruit and dump the peels before he returns to the helm.

Wade, a scruffy yet genial man, is every bit the Montauk captain—straw hat, mop of salty hair, beard, tattoos and all. He answers questions and watches the increasingly turbulent seas during our 1.5-hour ride south to Butter Fish Hole, an ideal area for spotting pelagic fish between Block Island and Montauk Point, just north of the Continental Shelf. This is where sharks feed in the summer, Wade says, explaining that blue sharks and makos spill in from the Gulf Stream during their long journey north, hunting fish pushed in from the Shelf, an underwater cliff where the seabed drops precipitously some 2,000 feet.

A member of East Hampton High School’s Class of 1986, Wade is a Montauk native with an easy, laid back manner, but it’s clear he’s deadly serious about safety and the desire for his guests to come home with a story to tell.

Initially, the captain and some friends built the shark cage for their own amusement, but he eventually saw the business potential. “It took off right away,” Wade says, noting that he’s the only guy in Montauk offering such an adventure.

Adding to his mystique, the captain moves south in the winter to dive for giant fossilized shark teeth off Cape Fear, near Wilmington, North Carolina. He appears entirely comfortable and capable at sea, and his confidence is contagious, even as The Sea Turtle begins to bob like a cork over the tempestuous Montauk Shoal.

Fighting the first near-bout of seasickness I’ve had in 37 years and a lifetime of boat rides, I introduce myself to John and Kristy Penney, a couple from Michigan visiting Montauk solely for the day’s excursion. Also on board is Montauk native and professional surf photographer James Katsipis, who’s also the first mate’s fiancé, and Gianna Volpe, a freelance reporter.

Just as I begin perusing a ragged and water-damaged Collins Sharks field guide, a massive pod of about 30 dolphins materializes, racing alongside and behind us. Wade does us the courtesy of looping around for a closer look and some photos before moving on.

The rain is falling harder as we reach Butter Fish Hole, but our collective excitement cannot be dampened. At first.

Wade and Ornaf get to the business of submerging the cage, cutting up baitfish, rigging fishing rods (without hooks) and dumping oily chum into the sea. The rest of us watch through rain-dotted windows, scanning in all directions—any sign of land has long since vanished, and an unbroken blue-gray horizon extends north, east, south and west.

Then the waiting begins.

The boat bobs, the sea laps, idle chatter comes and goes. Jokes are told. The captain and his first mate continue to chum, continue to hope. But nothing happens.

We wait and watch. They chum and cast and cut fish. They hope.

Soon, the rain still falling, my hope dwindles and I begin to mourn a lost opportunity. I’m resigned to accept that a decades-old dream isn’t in the cards.

But then it happens. The buoy disappears beneath the rain-speckled water. It’s a hit. Wade and Ornaf spring into action, doing everything they can to capitalize on our visitor’s interest, but the shark is gone as quickly as it came.

This is not totally unusual, Wade says, noting that blue sharks typically send a “scout” to investigate before others join the frenzy. So we wait some more.

And then they come. A dark form slices out of the water, its dorsal fin breaking the surface, and a shockingly bright swathe of blue catches the diffused sunlight. It’s a lot of blue, about 8 feet, in fact.

The Penneys enter the cage first, and more sharks come, five by day’s end.

I fight my way into a wetsuit and mask, and soon I am biting on a regulator and lowering myself, alongside Volpe, into the small cage hanging off The Sea Turtle’s stern. The sharks are circling and they are not shy about breaking the surface. Their jaws are dangerously close to the hatch I’ve just entered.

Beneath the surging water, I slip into a world of green. Only the sound of bubbles and bodies knocking against rows of bars can be heard, and I struggle to get my bearings as the cage bounces with each passing swell. Blue air hoses twist freely in front of and around me, but I eventually lock myself into place.

Drawn by bait from Wade and Ornaf above us, the sharks follow a tight path around the cage. In order to keep my fingers, which grasp the cage in two places, I watch the two graceful fish carefully, but they break rank and make it impossible to see both at once.

This is when I witness the shark’s dead eye up close. It is also the moment when, realizing I’ve lost the other creature, I turn to look behind me and find it bumping the bars inches from my face. It’s a startling moment and one worth the price of admission.

Everything settles and we hit a nice stride, watching and enjoying each moment with the so-called terrors of the deep. But as the minutes roll by, feelings of fear and anticipation give way to pure wonder, amazement and absolute respect for these resplendent marvels of evolution.

While seeing Montauk’s sharks firsthand, and not attached to a hook, is not, as Quint points out, “like going down the pond chasin’ bluegills and tommycods,” they’re not quite the monsters some would have you believe.

To book a shark cage or wreck dive with Captain Chuck Wade and Sea Turtle Dive Charters, visit seaturtlecharters.com.