Tarred and Feathered: Walt Whitman Teaches in Southold

The history of eastern Long Island goes way back to colonial times, to when the first eastern settlers landed in New England. Much of it can be documented with facts. Other bits of history, among them one of the most fascinating stories of all, cannot be fully documented.

Nevertheless, if you ask certain people from the Town of Southold on the North Fork about the story of the time Walt Whitman spent teaching school there in 1840, you will invariably be informed that everybody in town knows the story. It is in the lore of the town.

Indeed, a woman named Katherine Molinoff, who published a pamphlet titled Walt Whitman at Southold in 1966, came to Southold and spoke to people who said they knew of this story from their grandparents, who knew it from their grandparents. As a result of this pamphlet and other information, some historians accept the account as fact. Here is that story, including comments about what we know and don’t know.

* * *

When Walt Whitman was 36 years old, he first published Leaves of Grass, celebrating the common man, the gloriousness of life, the touch of God in nature throughout the planet and the freedom to ignore the encumberments of society and be your own happy self.

A hundred years later, in the 1950s, he was declared the grandfather of America’s Beat Poet generation, earning praise from Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Alan Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, who wrote On the Road. Keep moving. Love life. Enjoy every moment.

Even such varied individuals as Ezra Pound, Andrew Carnegie and Ralph Waldo Emerson offered him great praise. He is America’s greatest poet. One critic, William Sloane Kennedy, wrote that “a thousand years from now people will be celebrating the birth of Walt Whitman as they are now the birth of Christ.”

All that, however, took place when he was full grown. Earlier, as a youth growing up here on Long Island, which included several dramatic months here on the East End at Southold, he worked as a legal assistant, a printer, a schoolteacher, a pamphleteer, a newspaper editor and writer, which often involved the politics of the day, much of which involved Tammany Hall in Manhattan and all the corruption that went along with it. Once, in those early days, he got fired from his job as the editor of The Brooklyn Daily Eagle by writing in opposition to the political views of its owner, Isaac Van Anden. On another occasion he worked for The Long Island Patriot. He wrote against slavery being allowed in new states entering the union. Slavery in New York State had been abolished in 1828 (when he was 9), but children born into slavery would remain indentured until as late as 1853.

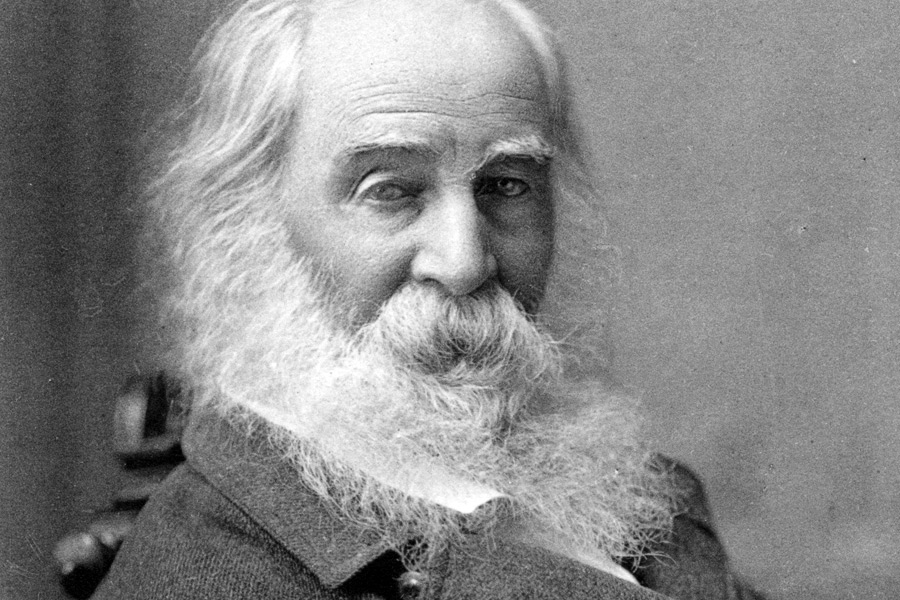

And then there was the time he spent as a schoolteacher. He was 21 years old at the time. Drawings made of him in 1840—this was before photography was widely used—show a slender, high strung, self-important young man who looks quite angry and troubled.

And in the summer of 1840, just four months before he reportedly came to Southold to teach, he wrote a friend of his a letter about teaching school to the children of the farmers of Long Island. He had taught at five schools from 1836 to 1838, and four schools in 1840 and 1841, and was probably the teacher at the Woodbury School at the time. Keep in mind that 15 years later he would be celebrating the “common man.”

“I am sick of wearing away by inches, and spending the fairest portion of my little span of life, here in this nest of bears, this forsaken of all Go[d]’s creation; among clowns and country bumpkins, flat-heads, and coarse brown-faced girls, dirty, ill-favored young brats, with squalling throats and crude manners, and bog-trotters, with all the disgusting conceit of ignorance and vulgarity. It is enough to make the fountains of good-will dry up in our hearts, to wither all gentle and loving dispositions, when we are forced to descend and be as one among the grossest, the most low-minded of the human race. Life is a dreary road, at the best; and I am just at this time in one of the most stony, rough, desert, hilly and heart-sickening parts of the journey.”

He also wrote: “Send me something funny; for I am getting to be a miserable kind of a dog.”

There wasn’t much in the way of getting references about prospective school teachers back then. Whitman left the Woodbury School. But then he gets this invitation from Southold, this is in the late summer of 1840 or 1841, that the Locust Grove School in that town needed a teacher, and would Whitman like to come?

Well, Whitman’s sister Mary—Walt was one of nine children—had moved to Greenport, just four miles east of Southold, after marrying a Greenport boat builder, so Walt had family out there. Why not?

There are only fragmentary records of what happened in Southold at this time. There were few town records kept. Only a few newspaper articles survive to this day. None describe the extraordinary things that some believe happened after young Walt came to town. But there is plenty of word of mouth about it.

Walt Whitman arrives to teach at the school in early December. He is taken in, as is customary in rural towns when schoolteachers are hired, at the home of George Wells, where he is to spend the semester living with Wells and his wife and several children, at least one of whom is a student at the Locust Grove School. There is no indication of the sleeping arrangements in that house, but it is common that the schoolteacher receive room and board. It is also common that he sleeps in the attic with one or more of the children he teaches. He is to be their professor, a member of the family, a friend and mentor. There are many references of this way of bringing a schoolteacher into a village in this period in America. And so young Walt commences teaching the young, about 25 of them, in a one-room wooden building with a lot of desks, some firewood, a blackboard and a pot-bellied stove.

During the first month, Whitman writes several fiery editorials that appear in the nearby Greenport Republican Watchman newspaper. People get very stirred up. They talk to one about their schoolteacher. Soon, the editor of the Republican Watchman announces that Whitman is “fired.” There will be no more articles from him.

And then, one Sunday morning, everyone goes to the Southold Presbyterian Church as they usually do.

The sermon is delivered by the minister, Ralph Smith, who in the course of things denounces the behavior of this young man named Walt Whitman. He denounces Whitman, and calls him a sodomite. He mentions the name of the family at whose home he is staying, and says they have a young boy in that family who goes to that school. He says this must be stopped. And at the end Smith refers to the Locust Grove School as “a Sodom.”

Records have been kept of the Reverend Smith’s sermons during that era, but there is no record of this lecture or any mention of Walt Whitman. On the other hand, there are reports by some who have seen these records that 12 pages of the records of these sermons that have been ripped out.

After the service, a mob forms out on the lawn. There are angry voices, declarations that something must be done. The mob heads to the home of George Wells, stopping along the way at Kettle Hill, a place where fresh hot tar is heated over a fire and available to all for fixing up house drafts, farm implements and fishermen’s seines. Hot tar is put in a bucket. The mob moves on.

Somehow, Whitman becomes aware of the mob. He flees the Wells house, and he heads down the street to the home of Dr. Ira Corwin, bursting in upon the housekeeper, Selina Danes, who hides him in the attic under a pile of tick mattresses. The mob, however, after talking to Wells and learning where Whitman went, marches on down to the doctor’s house and runs upstairs to find him there in the attic. They drag him downstairs and haul him out into the yard where they plaster his hair and clothing with tar and take him out to a wagon with the intention of putting him in the back and driving him out of town.

But then a woman named Aunt Lina arrives and comforts Whitman there on the ground, yells at the mob to leave him alone, and the mob melts away. Danes then takes Whitman back to Dr. Corwin’s house and, with the doctor’s permission, nurses Whitman there for a month without Whitman ever coming out of the house. Whitman then leaves the area quietly on his own after he has recovered.

That is the story that has been handed down about why, after that time, the Locust Grove School was no longer the Locust Grove School, but the Sodom School, a name that it bore into the early 20th century.

Whether all this happened as all the people Molinoff spoke to remembered it, I suppose we will never know. There are various bits of evidence either way.

For example, a letter has been found, written to a Southold man by a Washington lawyer early in the winter of 1840. The relevant part of this letter reads as follows:

“I am most sincerely sorry that Whitman tho’t it expedient to ‘run a muck’ under the chariot wheels of ‘old Tip’—but hope he may escape unscathed.”

“Old Tip” is a reference to “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too,” the campaign slogan of Whig candidate William Harrison (and John Tyler), who ran for and was elected President espousing that slavery continue to be legal in America. Reverend Smith represented the Whigs on eastern Long Island. Whitman campaigned for Harrison’s opponent, Martin Van Buren, who was morally opposed to slavery. Southold Whigs were very pro-slavery then. The country would continue along toward the Civil War.

On the other side, there are several articles written by Whitman that appear afterwards in Greenport’s Republican Watchman without any mention of these tar-and-feather events. But articles can be written from afar and mailed in and then published. Perhaps these were such cases. Whitman also writes a letter of recommendation that following spring to the Southold school district for a friend wanting to be a schoolteacher there. It’s also known that in the years that follow, Whitman, who continues teaching school elsewhere for a while,

summers in Southold, perhaps with his sister and her family. Finally, in later years, when he is old and is asked to remember all the schools he taught at, he remembers eight, but none are Locust Grove.

In 1850, at age 31, Walt Whitman writes that he is now going to leave off being an editor, printer and schoolteacher. He is to commit himself to being a vagabond and poet of the common man. He has long since forgotten, no doubt, the days when he described the common people of Woodbury as “country bumpkins, flat-heads, and coarse brown-faced girls, dirty, ill-favored young brats, with squalling throats and crude manners, and bog-trotters.”

Five years after that, in 1855, Whitman presents to his brothers one of the 795 copies of Leaves of Grass he has paid to have printed. The book is not yet the dramatic success it is later to become.

His brother George commented later that it was not worth reading.

* * *

You won’t be able to find the building known as the Sodom School today. It was sold in 1902 to a Mr. Hilliard for $42 and made into a garage. It later was used as a warehouse. After that, it was torn down. Probably just as well.