The Free Life Hot-Air Balloon and a Most Memorable Day in the Hamptons

Late in the summer of 1970, I learned through friends that several people would be trying to become the first to fly a balloon across the Atlantic Ocean from the New World to the Old, from a farm field in East Hampton to a farm field in Ireland, sometime in early September. It would be a professional attempt.

The man who wanted to do this was a 32-year-old Wall Street commodities broker by the name of Rodney Anderson. He had been planning to do this for years, before, during and after the landing of the first man on the moon in 1969. If we could go to the moon, surely we could go across the Atlantic in a balloon.

He had hired one of the best balloonists in the world to be his pilot. He had ordered something called the Roziere balloon to be built, which featured a new way to feed hot air into a balloon for greater success. And he was in East Hampton, with a crew and with his wife, preparing for the day.

Perhaps I would like to interview him? He and the crew first stayed in a motel, but now they were staying at the home of Mary Damark, a local woman who owned a deli on Three Mile Harbor Road and had taken a shine to them.

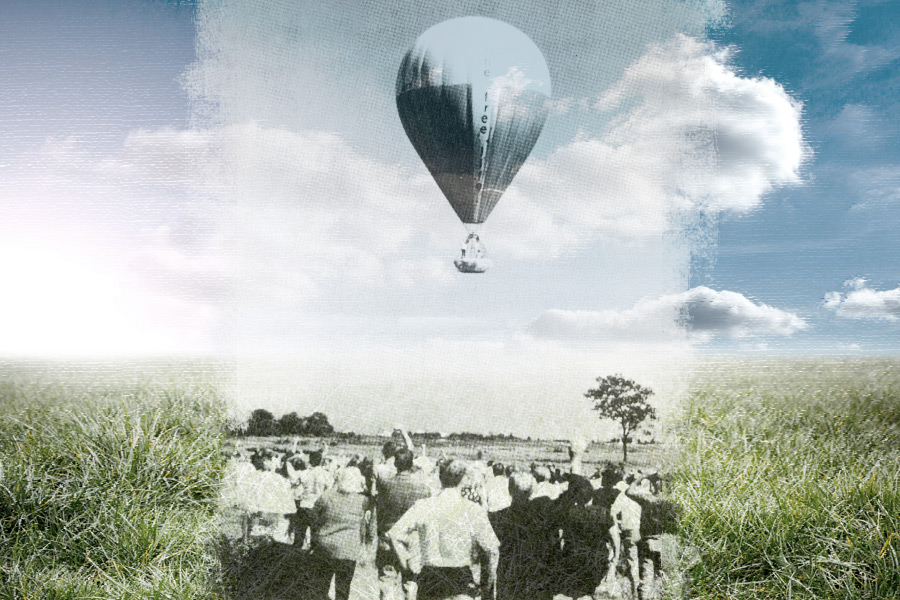

I certainly would want to set up an interview. An attempt was made. But as it turned out, it never happened. The first I was to see of Mr. Anderson was at the launch event itself, attended by over 1,500 people, on the huge bayside pasture of George Miller’s farm in Springs at around one in the afternoon of a beautiful September 20. It was not so much a launch as it was an event, or as we tended to call these things at the time, “a happening.”

This was a time in America when millions and millions of young people were transforming America and the way it conducted its business. They wore beads, headbands and bellbottoms, wore their hair long, drove brightly colored vans, espoused a drug culture, protested to end the Vietnam War, make marijuana legal, tear apart the military-industrial complex and otherwise turn upside-down the narrow tie-and-jacket crew-cut era of the 1950s with free love, rock concerts and a joyous approach to living on earth. Indeed, the first Earth Day was celebrated five months before the launch.

Today, you might express surprise at how this Wall Street commodities broker presented himself amidst the picnickers, guitar players and Frisbee throwers out in the southwest corner of the pasture of George Miller’s farm that day. But those of us present were not surprised. Rod Anderson, a slight young man with curly black hair, was in full hippie dress, from his boots to his bellbottoms to his cowboy shirt.

But he was not a smiley sort of person. He seemed quite serious, maybe a little nervous. But he was all business. He talked into microphones held out to him by the TV people. He shook hands with the local dignitaries. He made a speech to the crowd directly before the launch, standing beside this enormous and very colorful red, yellow and white balloon that was slowly being inflated by crewmembers hauling on ropes that fashioned to the midsection of the balloon that was now above our heads.

“As you can see,” he said, pointing to the words on the side of the balloon, “The name is ‘The Free Life.’ This stands for a new life, a free life filled with love and promise, that we now broadcast to the world. This will be a world-changing event.”

He kissed his wife, a dark-haired woman named Pamela Brown. She couldn’t stop crying, so filled she was with relief and happiness. Her husband was about to change the world.

Also there was Malcolm Brighton. He was not the original professional balloonist who they had hired. That man had backed out of the project a few days earlier. Malcolm Brighton had been hired from England, where he lived, flown over just a few days earlier, and was now the new pilot. Brighton was dressed in more traditional aviator clothes, which seemed more appropriate for what he had been hired to do. We all learned later, after their deaths, that this would be his 100th ascent in a balloon and, he had told friends, his last.

And then there was Anderson’s wife, Pamela. She was in her late 20s at that time, a beautiful black-haired aspiring actress, and she stood there holding the hand of her husband. We had been told that her father, John Y. Brown, a wealthy Kentucky attorney and state politician, had financed this whole project. But he had forbidden her to go.

It was amazing to me, wandering around in this wonderfully joyous affair of music, love, big shaggy dogs, picnic lunches, big shaggy dogs and the smell of marijuana that, with very little effort, I could walk over and actually touch the wicker gondola that at sat on the ground unattended while everyone worked the ropes.

There wasn’t much in there that I could see. There was a radio of some sort. There was sandbag ballast. And there was a case of champagne, and something I thought very odd. Glued to the interior walls of the gondola were, side-by-side, thousands of ping-pong balls. This was the floatation for this craft. Should it go down in the sea, the ping-pong balls would keep it afloat.

It was a slow business inflating that balloon to its full 70-foot height. But after about half an hour, the crew announced that it was done. There was a light breeze up there jiggling it around, so now things had to get a move on. I and some others were asked to step back, and in stepped the pilot, Malcolm Brighton, and then Rod Anderson, who immediately started waving and now smiling to the crowd. He was going. It was going to happen. His dream was coming true. The crowd shouted and cheered, and, slowly at first, the gondola began to drag and then bounce a little bit on the grass and move to the north and the end of that field.

And at that moment, a shriek was heard from the crowd, and out from it, running at full speed, was Pamela Brown, heading for the gondola. Tears were streaming down her cheeks.

“I’m going, I’m going,” she shouted. And as she shouted, her husband reached out for her and grabbed her by the arms and struggled her on board. As the gondola lifted off from the ground, there she was now, with her husband, the two of them, arms around each other, waving and smiling and getting smaller and smaller in the distance.

The image I have of these three in that balloon, slowly lifting off and heading out over that pasture, remains vivid in my mind.

This open pastureland extended for more than a mile from where we were standing, along the western shore of Accabonac Harbor and then ended on the banks of Gardiner’s Bay and the Atlantic Ocean beyond. There were just two trees on this property, and they were far off from the launch, with three or four horses grazing on the grass nearby and occasionally breaking off into a gallop.

The balloon passed right over the horses and these trees, and you could still see the trio in there, still waving at us, the gondola and its balloon getting smaller and smaller until finally they were out over the sea, now a small disk in the sky and then a speck.

That scene, to me, was like something out of a fairy tale. There they were, the prince and princess and their driver, gliding over the horses and off to Ireland.

The cheering went on and on for a while at the launching place, where we all stood still talking and watching, watching this little speck—I still see them, they’re THERE, to the left. The wind is taking them to the left.

Then things finally calmed down. I think we all felt, all 1,500 of us, we had witnessed something magical, something so special. It took all of us quite a long time to settle down, and then we began the mundane business of packing up, folding the chairs, rolling up the blankets, putting away the trash, gathering up the children and the dogs. And then, with many hugs and goodbyes, we gathered our stuff into our cars and drive off.

You couldn’t see them anymore.

What a day. Things like this change the world.

Late that afternoon, many of us talked on the phone to people we knew who had not been out there to tell them of what they had missed. This was a celebration, like Woodstock, but on a miniature scale perhaps appropriate for our rural community. It was a celebration of the revolution, and out there, after this fairy-tale launch, these two lovers and their brave pilot were slipping eastward over the Atlantic Ocean, pushed along by the prevailing gulf stream winds rushing them along toward Europe.

“They have radio equipment,” we told them. “I’m sure we’ll be getting the bulletins of what they have to say sometime soon.”

“I’m so sorry I missed this,” our friends would say.

That night, I attended a bonfire at Indian Wells Beach on the ocean at Amagansett, and there was more talk about this event. We were calmer now, though. I looked out to sea to the east. The waves and wind had picked up. There had been nothing reported from them yet. We headed home. Surely they were, two at a time, fast asleep in the gondola by this time, taking turns on the watch, maybe listening to their radios.

Late in the afternoon of the next day, people were getting a little worried about these balloonists. There still was no word from them. Obviously they were keeping radio silence.

How long was it to Ireland by balloon? Three days? Four? They had enough provisions.

It wasn’t until much later, years later, that we learned of the only contact the balloonists had with anyone on land on that first day. It was with a propeller-driven USAF Air Rescue HC-130 plane that was returning to its base from an assignment escorting American fighter jets partway across the Atlantic for a NATO mission in Europe. Here is part of the day log, made by a crewmember of that aircraft:

“On our late afternoon return leg to home base at Pease AFB, Portsmouth, NH, Boston Radar asked me on the frequency to attempt to make contact with the balloon crew. The crew had a VHF radio, some food and a case of Champagne on board! I was able to raise the Englishman off the coast of Nova Scotia. I asked him how it was going and he replied, ‘We are doing fine, however, we are a free gas balloon now, since we lost our burner during the night; but we are maintaining about 7,000 feet of altitude.’ I advised him of the potentially bad weather ahead of him on his flight, wished them good luck, and went back over on frequency to report to Boston Center what I had heard. After we reached Pease and had shut down the engines, I went into our Operations offices and told our air rescue alert crew to ‘get ready; you will be going out tonight!’ We had, just prior to contacting the Englishman, crossed a weather front at 20,000 feet with 70MPH surface winds and 30-foot wave swells on the water surface! Think: Perfect Storm!”

The next morning, we heard the news. In the darkness before dawn, the balloon had gone down to land on the ocean. It sounded okay, because here is what they had said:

“We are ditching. We request search and rescue.”

They would be just fine. They must be floating along, drinking that champagne. Too bad they didn’t complete the mission. But surely rescue would be along soon.

It is a big ocean. But the alarm had been sounded. The Coast Guard oversaw the operation, which consisted of three Coast Guard cutters, a Royal Canadian Air Force plane and six American Navy and Coast Guard planes for seven days. Many of the fishing boats from Montauk and Hampton Bays went out. Between them, they found a few items they thought came from the expedition floating 600 miles southeast of Nova Scotia. But that was all.

After the seven days were up, Kentucky’s John Y. Brown insisted there be a further search, and when he could not get that to happen he hired two private planes to continue the search for another week. But it was all for nothing. They were gone.

Here on the eastern end of Long Island, those who had celebrated this launch went into mourning. Many of us cried and cried. It seemed impossible what had happened. We had all been taken in. It was all about Mother Nature. And she didn’t care. These young people had died a horrible, horrible death by drowning. And why hadn’t someone stopped Pamela when she ran for the gondola? Why had Anderson put this project together in the first place? Had we all gone mad?

In the months that followed, many of us were forced to face the fact that our revolution to change America was largely beginning to fail. On the last day of April, 1970, five months before the launch, our president, Richard Nixon, announced that, in addition to his war in Vietnam, he was now going to launch an invasion into Cambodia, the country right next door. It would be only a foray, he said, one that might last a month or two. None of us thought he was telling the truth.

The next day, protests against this expanded war broke out in universities around the country. And after two days during which time students seized administration buildings and set other campus buildings on fire, National Guardsmen, instead of using fire hoses and tear gas, loaded their rifles at Kent State University in Ohio on May 4 and shot and killed six undergraduates.

There were other signs that the day of the cultural revolution was in its inevitable descent, including the explosion of the Weather Underground’s townhouse on West 11th Street in Manhattan and, ultimately, the poison laced Kool-Aid drunk by the cult followers of Jim Jones in Guyana, South America.

The fate of the Free Life was just our own personal marker of the beginning of the end of that era.

In October 1972, the first and largest theater inside the newly built Actors Theatre of Louisville (Kentucky) was named the Pamela Brown Auditorium.

There were to be seven attempts to be the first to cross the Atlantic in a balloon between 1970 and 1976. The seventh one, finally, succeeded.

Pamela Brown’s brother, named John Y. Brown Jr., served as Governor of Kentucky from 1979 to 1983. He also made a fortune with Kentucky Fried Chicken, which he bought from Harland Sanders in 1964.

In 1995, an avid balloonist in England by the name of Anthony Smith wrote an award-winning book titled The Free Life: The Spirit of Courage, Folly and Obsession.

Smith had not been at the launch and was not even in America at the time. But he had been one of Malcolm Brighton’s best friends and could not understand how Brighton could do what he did. He knew Brighton as a dedicated, careful balloonist. Smith had spoken to other balloonists who had spoken to Brighton just before he left for America to captain this voyage. Almost all had told him not to go. What had gone wrong?

Smith concluded that the Free Life Adventure had gathered so much momentum by that September that it had grown into a life of its own, that everyone had just gotten caught up in this effort and had lost all compass of what, if they thought about it, would surely amount to their doom.

Brighton couldn’t say no. And Pamela couldn’t say no. As for Anderson, he and his wife referred to this obsession of his as “the monster in their backyard” all during their short-lived marriage.

It simply had to happen.