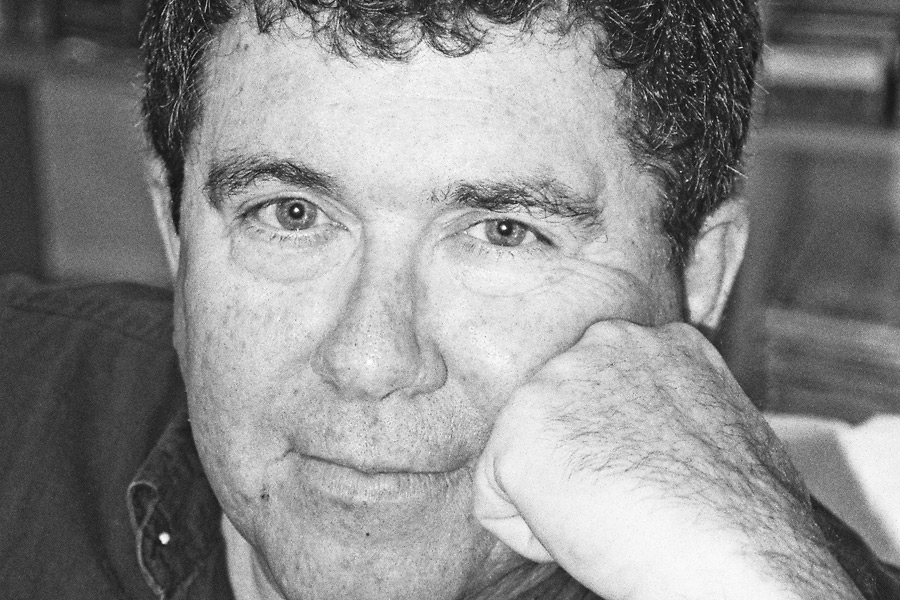

Who's Here: Tom Clavin, Author

Many people know Tom Clavin for his book Dark Noon. It appeared in 2005 and was the first thoroughly researched and passionately written account of one of the darkest days on eastern Long Island—the otherwise calm day at sea in 1951 when a single rogue wave overturned an open fishing boat off Montauk, loaded with fishermen having a good time, leading to the deaths of 46 people.

It was attributed, at the time, to an almost complete lack of public sport-fishing rules, an overloaded boat with one of its two engines out of service, no time to negotiate the mounting waves, and poor communication between boats and shore. All that has since changed, mostly as a result of the Pelican disaster, something that for many years people in these parts did not want to talk about. Among those who died was the captain, a popular Montauk man named Eddie Carroll.

Also changed was the career of the author of this book, Tom Clavin of Sag Harbor. His next book, in 2007, written with Bob Drury, about a little-known typhoon that capsized and sank three American warships in the Pacific during World War II, became a New York Times bestseller.

As Clavin said at the time, “I can do this,” meaning he could do what he loved and could make a living at it. It was true he had written seven books before. But none had sparked. Now, in his early 50s, one did. Subsequently, he has written eight books, all to great acclaim, including his latest, The Heart of Everything That Is, which came out last fall and also spent time on The New York Times bestseller list.

He has hopes of a similar reception for Reckless: The Racehorse Who Became a Marine Corps Hero, to be published on August 5 by NAL/Penguin. One of the early appraisals has come from Nelson DeMille: “It’s not too much of a stretch to say that Tom Clavin’s Reckless reads like a wonderful and inspiring combination of Laura Hillenbrand’s Seabiscuit and Unbroken. The star of this book might be a Mongolian mare, but she was an American war hero and her amazing story deserves to be told, which Tom Clavin so ably does. This would make a hell of a movie.”

Tom Clavin was born in 1954, the oldest child of an Irish-American family in what was then an Irish Catholic neighborhood in the Bronx.

“We lived on Bainbridge Avenue, up by Mosholu Parkway in the vicinity of Woodlawn Cemetery. This was St. Brendan’s Parish. My dad had been in the Navy during World War II and again during the Korean War. When he returned to my mother, who worked for New York Telephone, he sired me.

“We lived on a fifth-floor walkup. I went to the St. Brendan’s School, carried a little briefcase and wore a uniform. This was fine until my mom had two more kids, my sister and brother. She rebelled. She could not raise three kids in a fifth-floor walkup. And so, when I was eight years old, we moved to Deer Park, Long Island. There was no Catholic school. I went to public school. On my first day there, in my uniform and carrying a briefcase, I got beat up.”

The move to Deer Park was understood by his father, but grudgingly. Now he was working for Shell Oil in the city, and he commuted. He was now far from his extended family in the Bronx. In Deer Park at that time, there was no Catholic church, either. Mass was held in a rented movie theater.

His mother thrived in this environment. And she lavished attention on her first born. Back in the Bronx, she had taught him to read and write before he attended school. He loved the images the words created. Now at eight years old, she bought him a typewriter. Now he could write things.

“I wrote my first short story when I was 11,” Tom said. “Things that happened at home, but with fictional characters. The whole thing just took hold of me. I’ve loved it since.”

“Do you still have that typewriter?” I asked.

“It used to sit in the basement of our home in Deer Park, close to the furnace,” he said, “but the house was sold four years ago.”

When Tom was 12 years old, his father went to work one morning and never came back. He was found, days later, asleep in the subway.

“He lost the battle with alcohol,” Tom said. “He couldn’t even take care of himself, much less his family. He was gone. I didn’t see him but three or four times a year after that. He died at 68.”

Tom’s mother had no car, no income. It was, of course, the end of the marriage, and that immobilized her. “I had to work, my mom said. After school. I got a job delivering Newsday. Then when I was 13, with a friend helping me fill out a form so I could hide my age, I got a job at a rug factory.”

For a couple of years, a good job was cleaning movie theaters. He worked at two of them, one in Babylon, the other in Commack. By this time, he had a car but was still too young for a license. He drove illegally.

“If I got there early, say at 10 p.m., I could see the last show. The work began at midnight and went to 4 a.m. I watched for wallets.”

In the early years after his father left, and until his mother found a job working for a bank, there was sometimes nothing to eat.

“I’d come home and drop off my books and mom would say, ‘I don’t have dinner for everybody, you have to fend for yourselves.’ I was 12, my sister 8, my brother 6. I considered it a problem to solve. So I’d wait until around 6 p.m. and I’d go knock on the door of one of my school friends. ‘Can so-and-so come out to play?’ I’d ask. I knew it was dinner time. The reply would go like this: ‘Oh, we just sat down for dinner, (pause), would you like to join us?’ My closest friends kid me about this to this day.”

I considered this. Now he lives in Sag Harbor.

“Like who?” I asked.

He told me two of his closest friends, Tony and Patty Sales, now run the food operation at the Star Island Yacht Club in Montauk. He told me they remember it another way—they knew dinner was ready when the doorbell rang.

“Mom failed her driving test seven times, but got it on the eighth, then got the job at Security National Bank. Life got easier then.”

Tom finished at Deer Park High School. He became the president of the student council, and editor of the high school newspaper.

“I loved it,” he said. “It gave me an interest in journalism.”

Things were still rough at home, though, and for a few years he continued working during the day, he became a landscaper and went to school at night at Suffolk County Community College. But then a big change came over him. It was a kind of dream. There had been a time after his father left that his mom went to Tijuana for 30 days so she could qualify for residency for what would be a Mexican divorce. He and his siblings were dropped off with a relative.

“I was 14 at the time,” Tom said. “I loved Southern California. There were beaches, ocean, everybody was so laid back. I set my sights on going to USC.”

He would need money and scholarships. He got his mother’s blessing and moved to a $70-a-month studio apartment near campus.

“It was squalid, in the barrio. There was an old man with a head injury from a drug deal gone bad who showed me the place. ‘I’ll take it,’ I told him.”

He was determined to be a writer. When not studying, he wrote fiction. He submitted stories to magazines, got a shoebox full of rejection slips, but soldiered on, sometimes landing a piece. At USC he founded a literary magazine called Prufrock, filled with poetry and stories, and he buried himself in his studies.

“It was a good experience. I studied with so many students from so many different nationalities. Muslims, Asians, I really was exposed to South America. But every semester I had to fight for that $5,000 scholarship from the school.”

He never graduated, however. He left USC after two years to come back East and get married to a woman he had fallen in love with when he was going to Suffolk Community College. They were married in St. Joseph’s Church in Kings Park in 1976 by her brother, a priest.

His wife worked at the Viking Press in the city, in the production department, while he worked at the Guinness Book of World Records at their offices on 32nd Street in Manhattan.

“I did proofreading and press releases. But my real job was to greet people. Were they dangerous? Were they okay? I’d deal with it. For example, there was a woman who brought in two potty-trained iguanas that she wanted to show us. We took her word for it. Another man brought in a game, which was a mechanical rabbi that the dogs chased around a track. Honestly, I thought it was a ridiculous place to work. There was Japanese porno wallpaper in the bathroom. The president drank his lunch every day.”

For his trouble, he got fired.

He then worked for a while for Fodor Travel Guide to Mexico, proofreading, which was better, but that didn’t work out, either.

“I have had three jobs in my life, and got fired from all of them. I think it’s about authority.”

He began writing for national publications, contributing to the Long Island Section of The New York Times, where his editor was Stuart Kampel (“A wonderful man”). He found he could make a living doing this.

In 1982, he and his wife moved to Sag Harbor.

“I’d just read Deb Solomon’s biography of Jackson Pollock and wanted to live where he partied, worked inexpensively and drank, which would be East Hampton.”

He got as far as Sag Harbor, where a snowstorm stopped him long enough for him to fall in love with that community. He and his wife rented a house there. In 1982, they could be gotten quite cheaply. They had a daughter and a son.

Here on the East End, he found a place for himself with local newspapers. “I loved certain aspects of the newspaper business. Breaking news, deadlines, the routine of local sports, cornerstone issues, the environment, the land.”

He worked for two years for The East Hampton Star, then in 1993 was hired to be the editor of The Independent, a paper formed mostly by refugees from The Star.

“I didn’t think it was a good idea to become editor, because I was just beginning to break into books,” he said. “But they needed to get somebody to replace someone who was not working out.” He stayed almost 10 years.

Before going to The Independent, Tom volunteered to be part of the weekly Dan’s Papers editorial meetings, and I got to know him then. I so enjoyed his sense of humor, his approach to life and his attitude. After leaving The Independent (firing #3), a strange thing happened. It was as if he dropped off the face of the earth. There was no way to get in touch with him. Addresses and telephone numbers kept changing with alarming frequency. It was very strange.

What was going on for him, during this time, as I learned only recently when interviewing him for this profile, was that he was going through a prolonged separation that would lead to a divorce. He moved from place to place during it. And he wanted only to brood and be alone and do his work. It lasted several years. “But I think I was a good dad,” he said. “I went to school plays, helped raise my two children. We got through it.”

After writing books that included a biography of legendary golfer Walter Hagen, in 2005, out came Dark Noon, and Halsey’s Typhoon would be followed by The Last Stand of Fox Company and biographies of Roger Maris and the DiMaggio brothers.

His years of hermitage came to an end one day when a woman named Leslie Reingold showed up at a book-signing event. Sparks flew. They now live together, and he loves being back in Sag Harbor.

“Early on, I loved that it was a small town surrounded by water,” he told me. “It was a great place to raise kids. Now I love it for all the familiar faces, friends, and activities, both for grownups and kids. I could not find this anywhere else.”

His daughter, Kathryn, is a social worker who lives in Manorville. His son, Brendan, goes to Stony Brook University. Sometimes he and his son go off to play golf together, usually at the Sag Harbor links.

Tom Clavin’s other recent books include That Old Black Magic (2010), about Las Vegas in the 1950s; The Last Man Out (2011), about the fall of Saigon during the Vietnam War; One for the Ages (2011), about Jack Nicklaus and the 1986 Masters; and, with Danny Peary, a biography of Gil Hodges. The paperback edition of The DiMaggios has just been released, and The Heart of Everything That Is is a biography of perhaps the most powerful Indian chief of the 19th century, the Lakota Sioux Red Cloud.

There is much more to come, like Reckless, and, with the writer/director Peter Israelson, a TV miniseries on Custer and Crazy Horse and the Little Bighorn battle. I look forward to it all.

Tom Clavin will be speaking at the weekly “Fridays at Five” event at the Hampton Library in Bridgehampton on Friday, July 11, at 5 p.m.