Barry Trupin: Shark Tanks, French Castles, Hostile Neighbors and Scandal

In 1979, a stranger, who some believed to be a member of the mafia or worse, bought what was at that time the largest mansion in the estate section of Southampton.

This house was 55,000 square feet, had 60 rooms and stood oceanfront on Meadow Lane. It was built in 1926 by Henry F. du Pont, who lived in it with his family for many years as part of Southampton high society. Ultimately, when the family moved to Delaware, “Chesterton” as it was known, began to fall into ruin.

In 1979, an auction was held on the front steps of that run-down mansion. I attended that auction. It was a drizzly, foggy summer’s day. The property loomed, a great pile of bricks covered in vines. The auctioneers came in a station wagon that had a public-address system in the back, and they set that up in the potholed driveway and ran a wire to a microphone on a stand on the front steps of the house. About 40 people came, and they stood under umbrellas. I recognized some other reporters, some farmers, real estate people, a few lawyers and some officials. Only one, a man in a business suit with an attaché case, was interested in bidding.

The auctioneers tried to jump start things. They had this opening bid, which apparently had come in advance. But there were long silences.

“Sold for $440,000,” the auctioneer finally said. And the man who apparently had made that bid stepped forward and that was that.

Who was this man, everybody wanted to know? He wasn’t telling. Some papers were signed in the front seat of the station wagon. And then everybody went home.

Soon, the word came out. The man with the briefcase was a lawyer representing the firm Rothschild Reserve International. But it was not the real Rothschilds. In spite of the name “Rothschild,” nobody who was anybody in this high society had a clue what this firm was. And everybody wanted to know.

Eventually, the name Barry Trupin came out. People still didn’t know who he was. He was certainly not part of any above-board business. He seemed to be a shady character. Rumors swirled that he was a member of the mafia. Or a drug cartel.

It did not help that soon after the sale, a chain link fence was put up around the entire property, with an armed guard at a small wooden construction shack at the driveway entrance. The fact that a weapon was involved terrified this otherwise polite society.

People told their teenage and pre-teen children that after dark they should not walk along the beach in front of this property. Someone said they had heard a helicopter landing there one night. A full-page ad was taken out in The Southampton Press at this time by the Southampton Association, a group that represented the summer people who lived in the estate section of that town. Headlined “The Law is Being Broken Today in Our Village,” it basically demanded that Roy Wines Jr., the head of a local plumbing firm and then the mayor of that community, instruct his village trustees to reject whatever project was being proposed for the restoration of the du Pont estate. In this summer community, all the rich summer people knew everybody, and went to one another’s cocktail parties and coming-out parties. They did not want this.

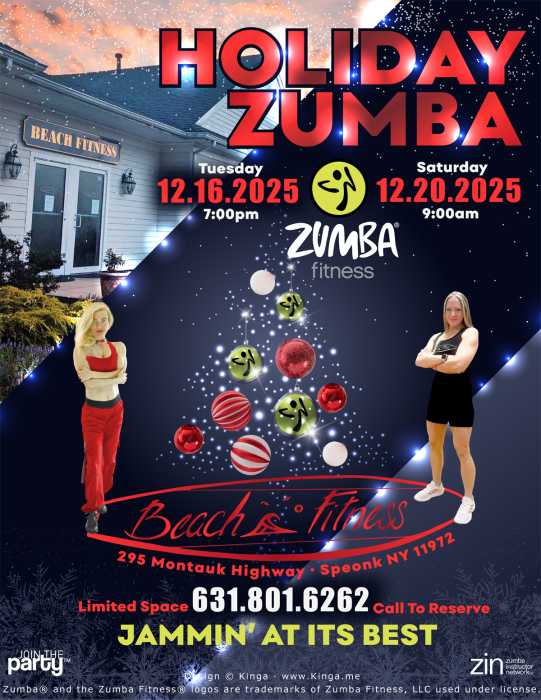

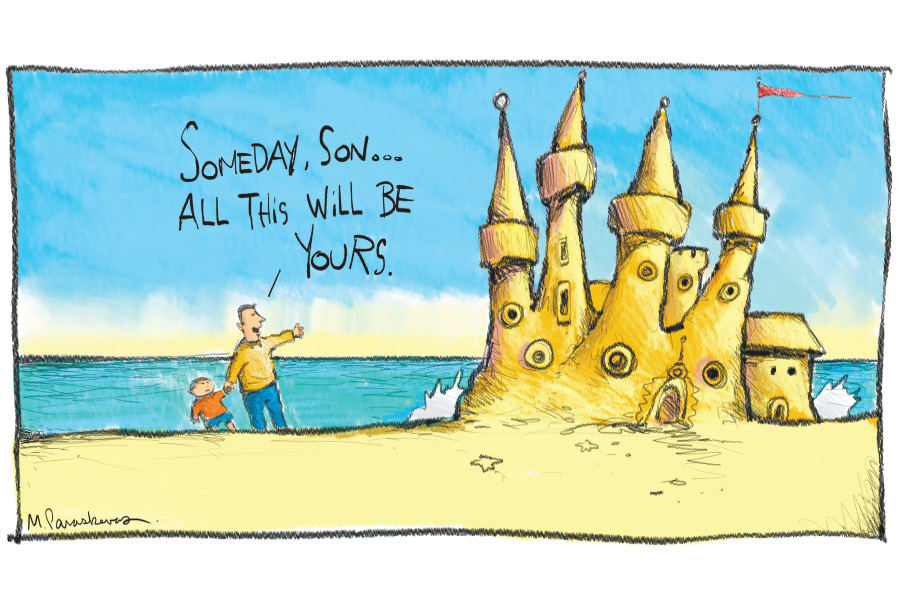

The home was being built as a French castle with turrets 40 feet high, exceeding the legal limit by 5 feet. This man, whoever he was, should be run out of town.

As it happened, I turned out to be the person who pulled the veil back to reveal who Barry Trupin was. It came about this way. At the time, a handsome older man named Robert Keane owned a bookstore on Hampton Road that bore his name. He specialized in local history books among many other things. And he was well known and respected in the community.

One day, I was browsing in the shop when Keane smiled at me—he knew who I was—and said he thought a new book that had just come in might make a good story for Dan’s Papers.

“It’s about Elias Pelletreau, the world famous Southampton silversmith from the 18th century.”

I was puzzled. He handed me the book. I was still puzzled.

“There’s lots of books about him,” I said.

“Look at who wrote it,” he said.

The author was Bennett Trupin of Hallandale, Florida.

“He was here last week and left me 10 books on consignment. A nice old man. Retired. He owned a silverware factory in New Jersey that makes this sort of thing and he’s done a scholarly book on Pelletreau. And he has a son who has gotten very rich and he’s very proud of him. He’s visiting him for a week.”

“I think I ought to invite Bennett to lunch,” I said.

We ate at Barristers on Main Street and I pretended to be interested in the book he had written. I felt bad doing this, but I would write about it to make up for it. I steered the conversation around to his son.

“Barry Trupin has made hundreds of millions of dollars for his clients,” Bennett told me between bites of a pastrami sandwich. “He’s found a loophole in the tax code through which businesses can avoid paying billions of dollars in taxes. Say Ford has a fleet of trucks but is losing money. It could write off the cost of the trucks if it were making money. So say American Express did not have any trucks but was making money and could use this tax deduction. Barry arranges for Ford to “sell” their trucks to American Express and then lease them back. The trucks don’t go anywhere. American Express gets that tax deduction. And they share it with Ford and with Barry. Barry is brilliant.”

I also learned that Barry Trupin went to Adelphi College, owned a bar in Manhattan with a partner for several years and then worked for Republic Aircraft on Long Island at a job where he had high security clearance.

The day after I published all this information in Dan’s Papers, I got a phone call from Barry Trupin inviting me to his home in Southampton to have lunch with him. He’d like to know me better.

The Trupins, it turned out, were not yet living on the property they had bought. It was under construction. There were workmen everywhere. It would take several years to convert this home into the French castle he had in mind for his wife, Renee. They lived in another mansion, a smaller place (20 bedrooms) five mansions down the beach on Meadow Lane, which they rented. Barry and Renee and my wife and I ate lunch under an open tent on the lawn of that home between the house and the beach, a six-course meal served to us by waiters and footmen that were part of the Trupin entourage. They had a private chef and baker in the kitchen as well. It was, frankly, with the roar of the ocean, the rustling of the silk tent in the wind, the courtesies offered by the hosts and the warm sun, one of the best lunches I ever ate.

“I am building this mansion for my wife, Renee,” Barry told us. Renee, who sat beside him, was as beautiful as you could imagine. “She wants to join Southampton society. You know how things go,” he smiled, “whatever she wants, I see that she gets it.”

He and Renee drove us in one of their Rolls-Royces down the street to what was to be this French castle. We were welcomed in by the armed guard. We met the architect, the foreman, some of the workers. One group of them only spoke Italian.

“We brought them in from Italy,” Barry told us. “They are artisans and will be living here for two years. They carve marble. Follow me. I want to show you this 16th-century English pub we have already installed. I bought it in England and it’s been reassembled here.”

It occupied a large room that faced the ocean. The bar was open and set up. There was a fire in the fireplace. We had drinks.

Trupin took us upstairs. He showed us the prayer room that he was installing in one of the turrets, partially completed. An orthodox Jew, he would pray up there. He showed us their master bedroom under construction. The gold plumbing had recently gone in, but much work remained to be done. There was a made bed in the room.

“Sometimes we camp up here,” Renee said, a twinkle in her eye. “Nobody knows. But we don’t have any C.O. yet. So don’t write that.”

A grand staircase was under construction in the great entry hall. We went into a living room with workmen painting the walls. It was the size of a school gymnasium.

“I’ve taken out all the little bedrooms,” Barry said. “We will have only 12.”

Barry showed us the greatest feature of this home. In a separate wing, there was an indoor swimming pool made to look like a pond. It had large stone walkways that led from boulder to boulder. Just below the surface of the water there were odd steel nozzles you could attach a hose up to. I asked about it.

“When this is done,” Barry said, “this pond, will be stocked with fish, including sharks. You’ll swim among them in scuba gear. When your air runs low, you attach to these nozzles and charge up your tanks.”

Walking back to the car that had taken us to this construction site, I glanced at some portable buildings that appeared to be construction trailers.

“That’s where the Italians live,” Renee whispered.

Back at the house they were renting, we had afternoon drinks and then Renee led us down into the basement to see a “surprise.” There was a boardwalk, and alongside it an enormous collection of mechanical games that you could play—things with metal balls that came down chutes, roulette wheels, guess-your-weight machines, metal horse-racing games. There were 50 or more. Trompe l’oeil murals of a seaside amusement park adorned the walls.

“I collected these from amusement parks that had them for sale,” she said. “This is my own private Coney Island.”

All would be transferred to the new home when completed. Also to be transferred, up in the living room, were numerous wall hangings, spears and shields and suits of armor that stood along the walls of the living room of their rental. A great oil painting of Renee stood over the fireplace.

My wife and I became friends with Barry and Renee. Barry, a nice Jewish boy, had grown up on Long Island before making his fortune. Renee was another matter. She had grown up Catholic, a daughter of an officer in the military who moved from military base to military base. Mostly, her homes had been in the Midwest.

Occasionally, we ate in restaurants in town where, when they entered, they were treated like royalty. Barry sought advice from me, which I freely gave. He knew about the troubles with the neighbors. I hoped all this would work out. I advised him to take away the guard at the place and he said he could not.

“I have very valuable paintings and antiques that will be going in there,” he told me.

Egged on by the Southampton Association, the mayor had a stop-work order issued. And the war began. Barry said he was being persecuted because he was Jewish. He said he had a right to be treated as anyone else was. He said he would file a lawsuit about his civil rights.

I counseled that he reach out to the Southampton estate residents. He thought it worth a try. He and Renee held a huge party at their rented home, a costume party at which a huge boar was served with an apple in its mouth. Everyone dressed as royalty, as Romans, as barbarians. It was quite an affair. But my wife and I were not invited, so I do not know much more about it except that afterward the neighbors said it was fine but they still wanted them out.

Then it turned out that Renee had built the kitchen on one side of the house, but then said she changed her mind and wanted it built on the other side. Mayor Wines was their plumbing contractor. He did the work. It was said he had billed them, so far, more than a quarter of a million dollars. He should resign from being mayor. And he did.

Wines’ successor as mayor was a Wall Street broker named Bill Hattrick, a well-liked man, a member of the social set and someone who, of a liberal persuasion, felt he could work through this tangle. But it was not to be.

A few weeks later, a picture of Barry, carrying his bride across some imaginary threshold in front of the partially completed mansion, appeared on the cover of New York magazine. In the article that accompanied this cover, a reporter had asked one particularly vocal Southampton socialite, a woman named Charlotte McDonnell Harris, if she objected to the Trupins because Barry was Jewish.

Her reply became a landmark in this case.

“You said it, not me,” she replied.

It also turned out that many people in the estate section of Southampton were building illegal additions to their homes BEFORE getting variances to do so. It was speedier to do it that way. And so Barry filed a $4.5 million lawsuit against the village for violating his human rights. And then he called me to gleefully tell me that the woman who had declared her prejudice in New York magazine had built a porch that way.

One month later, that woman suddenly died. Here was Barry’s comment: “God struck her down.”

I visited the new mayor. He had an imaginative solution to all of this. He had proposed that Barry have a bulldozer bring in fill to one side of the house so the land would be higher on that side. If he did that, the offending turret would now be 33 feet above grade, not 40. He could rescind the stop-work order. He could go ahead.

I urged Barry to accept this. He said he had. But he had insisted there be a time frame in which they could agree on it. That had passed. And now he’d made a decision. I’m moving out, he told me, and we will be selling this home to black people.

Barry and Renee left, and the lawsuit proceeded. But Barry never rented the place. Nor could he sell this uncompleted property. Two years later, a jury decided that the Village had discriminated against Barry and Renee Trupin. Trupin was awarded $1.9 million in damages and the Village was ordered to pay all legal costs, for a total of nearly $3 million, which, according to the Mayor, they did not have.

“This will bankrupt the village,” he said. An appeal wore on. And the village lived with this cloud over its head for another year, until an appeals court overturned the decision on a technicality.

Eventually, the Trupin castle was sold for $2.3 million to Francesco Galesi, a New York City developer who took down several of the turrets a few feet and lived there summers for a generation with his wife and children.

Eventually, in the overheated real estate market in 2003, the castle was sold for just under $30 million to Calvin Klein, who eventually had the whole thing torn down and replaced with a smaller glass-and-stone modern structure designed by architect Michael Haverland of East Hampton.

The last time I spoke to Barry Trupin was in 1995. He was calling me from his yacht in the Mediterranean and he told me he was doing fine and investing in shopping centers in Southern California, using money he had arranged from savings and loans.

A few years after that, Barry was convicted of $6 million in tax evasion, accused of hiding personal money in corporations he ran. (He had also been convicted in August 1995 of dealing in stolen artwork after he tried to sell a Chagall). The latest appeal to his tax conviction that I can find came in 2007, when his 3.5-year prison sentence was confirmed. He was released from prison in 2006.

I corresponded with his ex-wife Renee for a number of years back and forth by email. She had divorced Barry and now lived in the South of France as an aristocrat. She goes by the name Renee d’Arcy.

France, I suspect, loves her.