'Hotter Than a Matchhead,' New Tell-All, Rockin’ Memoir by The Lovin’ Spoonful’s Steve Boone

Local boy Steve Boone is a happy man these days. Among other good news, he just bought a boat, and he loves boats. “It’s a cabin cruiser,” he reports in a phone interview from the Florida coast. “I hope it doesn’t need too much work!”

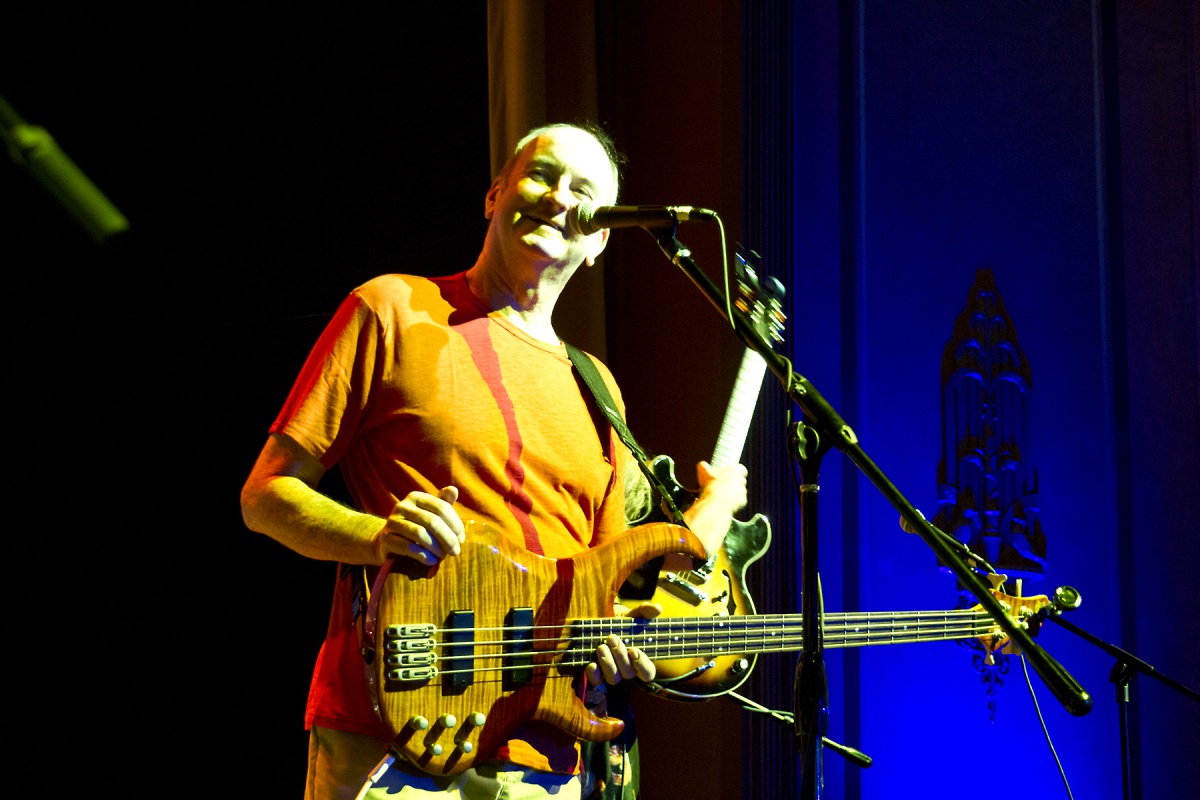

Whatever the boat needs, Boone’s up for it. A member of East Hampton High School’s Class of 1961, the man’s a dynamo—piloting boats, driving sports cars (he prefers BMWs), and of course continuing to play bass on tour with the Lovin’ Spoonful, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame band he helped to found in 1965.

“I’m 70 years old, and having a great time,” he says with some relief.

It hasn’t been smooth sailing getting there. To fill us in on the details, Boone has written an autobiographical book, Hotter Than a Match Head [ECW Press]. It tells the story of a life marked by astonishing highs and serious lows. From writing and recording top-ten singles and appearing on The Ed Sullivan Show with the Lovin’ Spoonful, to getting busted for marijuana possession and winding up addicted to heroin, Boone has experienced a lot. Hotter Than a Match Head is a gripping read.

As it happens, boats figure pretty heavily in the story, starting right from page 1.

Page 1 is where we read about Boone, fallen on hard times in the 1970s, piloting a boat smuggling marijuana from South America to Baltimore Harbor. It may seem incongruous that a man can go from playing the bouncy, innocent “Do You Believe In Magic” on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1967 to engaging in international drug smuggling about 10 years later. In our interview, Boone implies that it might have been in his blood.

“My dad grew up in Westhampton Beach during Prohibition, and it wouldn’t surprise me if his family was running illegal hooch,” he says with a laugh.

But the smuggling Boone did in the ’70s was clearly borne of desperation, as well. As the Lovin’ Spoonful’s recordings fell off the airwaves in the early ’70s and Boone found his rock star status slipping away, his rock star habits, including expensive cars and expensive drugs, continued unabated.

He went into smuggling because he knew how to handle large sailboats, and smuggling was a way to make it pay—big time. The promise of a $125,000 payday in 1977 must have made it pretty easy to fall into illegal activities.

Truth be told, Boone had really just kind of fallen into rock stardom to begin with. The book explains how, as a child, living in St. Augustine on the east coast of Florida where the family had moved for medical reasons, Boone had dreamed of a military career like his father’s. And he would probably have pursued it if a serious leg injury hadn’t canceled that option. Later, in early 1965, even as the newly-formed Spoonful were honing their chops in the Hamptons (rehearsing at the Bull’s Head Inn in Bridgehampton), Boone himself continued to entertain non-musical aspirations—he thought about a career as an automobile designer. He adored cars, having spent a great deal of time at the Bridgehampton Race Circuit, and he had paid his registration at the then-new Southampton College.

“I loved the idea of that campus, it was perfect for me” he remembers in our phone call. “I was really excited.”

The ambivalence Boone felt then—the sense that he could have been as happy designing cars or sailing boats as playing in a rock band—sticks with him to this day.

“As a musician and a bass player, I feel like I’ve always been on the outside looking in,” he notes. In Hotter Than a Match Head, Boone recounts how, even at the height of the Spoonful’s popularity, he would frequently slip away from his bandmates to hang out with the grease monkeys at an 88th Street motorcycle shop. And he was always eager to get back on the water.

On a deeper level, Boone seems to feel that music, or more specifically the music business, shares some of the blame for the problems he has dealt with in his life. In the book, he describes how shady business deals struck when the Lovin’ Spoonful was flying high later led to frequent financial hardship. Certainly the availability of drugs, including hard drugs, in rock circles could have been a factor in his struggles with addiction. Also, he met, and sometimes wound up marrying, some pretty marginal women. (He is now happily married to Lena, wife number four, who is quite normal.) And, for all of the Spoonful’s success and Hall of Fame induction, he remains frustrated with the critical standing of the band. In an interesting passage toward the end of the book, Boone is almost wistful about the comfortable, suburban existence that might have been his if he had actually enrolled at Southampton College.

But when the phone conversation turns to music, you can sense Boone’s continuing love for what he does, now that his life is on an even keel. Clearly, along with the boat and his wife, the ongoing success of the Lovin’ Spoonful as a touring group is another great source of contentment for him.

In the book, we learn that Boone’s love of music started early. He describes being blown away when he first heard “Peggy Sue” by Buddy Holly while he was still living in Florida, and in our phone call he adds that he was also drawn to the sounds of Hank Williams and Buck Owens.

“The airwaves were pretty saturated with country music down in Florida,” Boone points out in conversation, noting how he learned to play guitar listening to the Everly Brothers, his favorite. “The first thing I played on the guitar was their song ‘Dreams.’” He and his older brother Skip formed their first band while still living in St. Augustine. Later, this early experience with country music would be a strong influence on the Spoonful, heard especially in Boone-penned songs like “Butchie’s Tune” on the album Daydream.

Dan’s readers will be especially interested in the parts of the book dealing with Boone’s pre-Spoonful days playing music in the Hamptons. Boone’s family moved from Florida to the Hamptons in 1958, settling in East Hampton, and Steve and brother Skip delved in to the music scene out here. Local readers of a certain age will certainly recognize names and places mentioned in this portion of the story. In 1961, Skip formed the Kingsmen, a band that included future Spoonful drummer Joe Butler, and Steve soon joined the band. The Kingsmen played all over the East End, including at the Cottage Inn in East Hampton and Herb McCarthy’s Bowden Square in Southampton (now the Publick House). It is more than likely that some readers will recall these shows.

Boone still has a lot of family in the Hamptons, and makes frequent visits to the area. “I like Florida,” he admits, “but I don’t know of anywhere more beautiful than the Hamptons in August.” We look forward to seeing him soon. Until then, grab a copy of the book!