Center of Town: A History of Downtown Bridgehampton

When I first got here to the eastern end of Long Island in 1956 at the age of 15, Bridgehampton was a farm town. Almost completely surrounded by potato fields, it was where the potato farmers, mostly of Polish extraction, went at 5 a.m. to meet at the Candy Kitchen for coffee and to discuss the previous day’s potato prices before heading out to the fields. There were five large potato packing barns where migrants from the South worked in the fall, getting the potatoes bagged and off to the warehouses of Riverhead.

On the four-block-long Main Street there were six gas stations where farm equipment could be repaired, and there were several big farm fertilizer, feed and equipment stores, including a big Agway. The Bridgehampton Bank, in the center of town, was the most imposing commercial structure in town. (It is Starbucks today.) There were four churches, and a Baptist church for the African-American community on the turnpike. In the summertime there were visitors—a few New York summer people, but there was also another kind of summer people, young black men in shabby clothes who hung around on street corners, enjoying the sunshine and occasionally taking swigs of Thunderbird from paper bags. They were between shifts from picking potatoes.

Bridgehampton was at that time, therefore, a no-nonsense year-round town of commerce and industry. In the adjacent towns of East Hampton and Southampton, there were hundreds of wealthy summer people living in mansions down by the beach, mostly from Wall Street or Madison Avenue, and they had been coming out here for generations. There was a Blue Book of who they were that they distributed amongst themselves. Either you were in or you were out.

In 1968, after living for many summers with my parents in Montauk, I finished my education, and, with three years of graduate school in city planning and architecture at Harvard, moved to Bridgehampton. Dan’s Papers was eight years old at this time and it had paid for my education, both undergraduate and graduate. This education had made me keenly aware of civic matters. And, as a matter of fact, publishing a newspaper put me in a position to make some sort of contribution to the community to help make it a better place.

Bridgehampton was what it was. But there was one aspect of this town where the elegant place it once was a hundred years earlier showed through. It was what faced out to the Founders Monument on Main Street in the center of that street where five roads came together marking the center of town.

The Monument itself was built in 1910. And what faced out upon it from those corners in that year was as follows. On the northeast corner was a four-story-tall Greek Revival mansion built for a prosperous local family around 1840. On the southeast corner there was another four-story-tall Greek Revival mansion built by another prosperous local family. On the northwest corner stood Wick’s Tavern, a favorite stopping-off place since the Revolutionary War. And on the southwest corner was an open field that had been the parade grounds for the Bridgehampton Militia during the revolution.

Here’s what I saw in 1965. On the northeast corner, the Greek Revival mansion was in disrepair and on its last legs. On the southeast corner, the Greek Revival mansion was occupied by a reclusive gentleman who did not have the funds in any way to keep that mansion in repair. The grand columns were supported by two by four pieces of lumber nailed to them and nailed to the main house on the other side. The front lawn had, incredibly, been rented out to an oil company that had built an Esso station there. This was the era when gas stations had repair bays, with lifts, equipment and tools, and the men pumping the gas (and cleaning your windshield) were covered with grease and oil from making those repairs.

The northwest corner had a sign out front that said this had formerly been the site of Wick’s Tavern. The tavern had been torn down in 1941 to make way for a Shell gas station. So much for any appreciation of history at that time.

The southeast corner now consisted of a two-story building that featured a wing of six or seven local stores, including a butcher’s shop and a liquor store built in the 1920s. The building was not unattractive. It was white stucco and well kept. But now there was no sign of any Revolutionary War mustering ground.

Compare this to East Hampton and Southampton. In 1965, both these town’s main streets were filled with historic structures, parks and greens that had survived from the beginning of their settlement. There were windmills, ponds in the center of town, old saltbox homes on Main Street from the Colonial era. Southampton was founded in 1640, Bridgehampton in 1644 and East Hampton in 1648. That’s what the signs said when you entered these towns. But where was anything historic from that era in Bridgehampton?

I came to care a great deal for Bridgehampton when I moved there. At the time, my dad, who had bought the Montauk Pharmacy back in 1956, encouraged me. “You can enjoy the activities of East and Southampton,” he said, “but then, when you want to relax you can get away from all the bullshit to your house in Bridgehampton.”

From 1965 to this day, civic-minded people have helped restore the middle of downtown Bridgehampton. From my posts as editor and publisher, I’ve encouraged them and when necessary, objected to some things I thought inappropriate. And today, it’s almost done. It should be just beautiful by next year. The rest of this story will recount what has happened on those four corners in the middle of town.

It started, on the northeast corner, with a setback. Shortly after moving there—and the Dan’s Papers offices moved to a building I bought at the other end of Main Street in 1968—I learned that the Sunoco oil company had proposed buying the northeast corner, tearing down the Greek Revival mansion there and replacing it with a gas station. There would now be three gas stations on these four corners if this went ahead.

In the newspaper, I announced the creation of the SAVE THE BULL’S HEAD INN committee, which was the name of the building on that northeast corner. The committee consisted of me. I published a front-page ad urging all residents to cut up their Sunoco credit cards (oil companies had credit cards in those days) and mail the pieces to the president of Sunoco in Philadelphia.

A lot of people apparently did that, for soon I got a call from some executives of Sunoco asking if they could meet with me to discuss their plan. We met in New York City, in the townhouse apartment of a girlfriend I was seeing at that time. The men unrolled an architectural plan that showed something these men thought our committee should approve of. They would move the Inn at their own expense to the back of the property and turn it sideways to face out on the Sag Harbor Turnpike. That should satisfy the membership.

“So there would be two big mansions facing each other with gas stations on their front lawns, then,” I said, stroking my chin. “I’ll bring it up at our next meeting.”

That’s all we want you to do, they told me.

So that was that.

The next thing that happened on that site was that a local auctioneer and farmer named Charlie Vanderveer bought that mansion and proposed to the town that it become an inn open to the public with other amenities around it, which would include a spa, a conference center and a pond on the front lawn at which local kids could go ice skating. I wished Charlie well with that, but the town turned him down. Too much activity on that site, they said. Charlie then sold it to Lynn St. John, another resident of the town who kept the place up moderately well and ran it sometimes as an antique shop on the ground floor. Eventually, in 2005, former Philip Morris CEO Bill Campbell bought the place and submitted a plan that would be even more interactive than the one Charlie proposed.

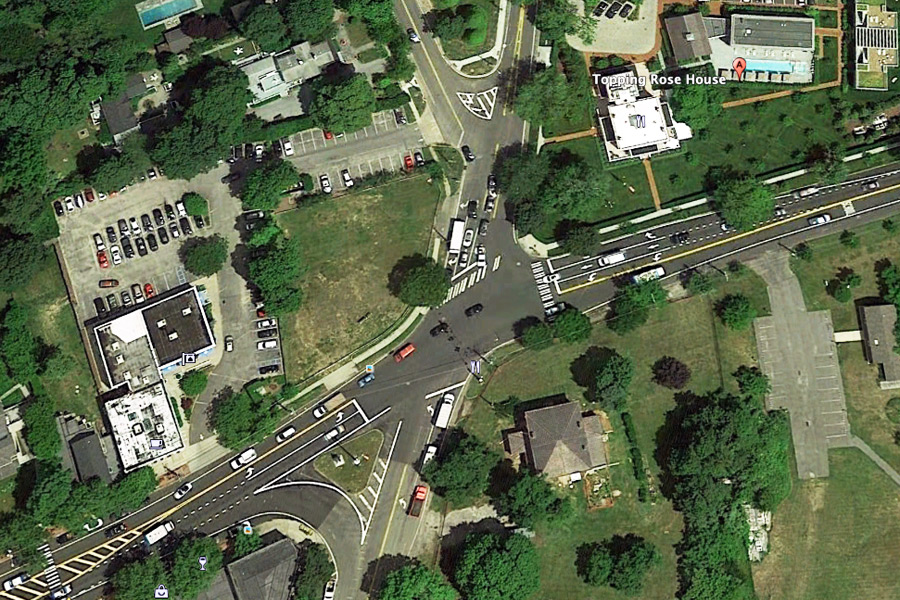

But this was now a different era. I was vacationing in Hawaii when I learned of it. Lynn St. John sent me the architectural plans for it, urging that I come back home and fight against it. But now I could see that Campbell had bought adjacent properties and it was now on a much larger campus. I thought it a great idea. The building would be completely restored. In the paper, I urged that it go ahead. And it did. Today it is the Topping Rose House, and it includes a corporate meeting room (in the barn) a lap pool, a spa and on the newly bought property, about 16 new guest rooms.

Across the street on the southeast corner, a Southampton town councilman named Dennis Suskind (a former partner in Wall Street’s Goldman Sachs and today the President of the Hampton Classic Horse Show) spearheaded a drive for the town to buy the other Greek Revival mansion so it could be restored and turned into a museum. It too succeeded. I loved it. The gas station was torn down and the building fixed up. It’s not yet open. But hopefully it will be by next year.

On the northwest corner, where Wick’s Tavern once stood, the gas station closed around 1975, fell into disrepair for five years, and then re-opened as a Beverage Barn. It was kept in disrepair, however, and during the next 35 years it fell into a state so bad it was a disgrace. I wrote about that and got a dressing down from the owner of the Beverage Barn, who was just the tenant there. What could you do? In 2006, though, East Hampton developer Len Ackerman bought the property, the tenant left, and everything was torn down. Now it was open land. What would happen to it?

I spoke to Lenny Ackerman. He was preparing drawings to create a two-story commercial building on that site. He had not yet decided what it might look like. He wondered what his chances were in getting it through. I told him he should build the structure as a third Greek Revival building. He did that. And the plan was approved. Ackerman did not build it, though. In 2011, he sold the controlling interest in the property to a New York City developer who later announced construction would begin and the tenant would be a CVS drugstore.

Protests began on that site against having a CVS there. There was inadequate parking, opponents said. It had been intended to have offices on the second floor and perhaps six boutiques on the ground floor facing out onto the sidewalk—a good walk for strollers downtown. The CVS plan would need an additional approval of the town, a special exemption permit. The plan for the new Greek Revival building could not accommodate any retailer occupying more than 5,000 square feet, according to town code. CVS would occupy both the 4,500 square feet of the first floor and the 4,500 square feet of the second floor. Where would people park?

The town planning board, responding to the protesting townspeople, said this new project would require an environmental impact statement before it could even be considered as a 9,000-square-foot exception. CVS, in response, filed a lawsuit against the town planning board.

In the course of things, one of the protesters told me there was talk that there might be oil spills from the old gas station underground, perhaps making this an unbuildable Superfund site if true. I wrote about that. I also suggested that the town buy the property now, and rebuild Wick’s Tavern there.

At this point, quite suddenly, the developers of this building broke ground and began construction. They had an active building permit. Why not? They dug down deep enough so anyone could see there was no gas and oil under there. And during the next few weeks, it is expected that the steel will be going in as the building, this Greek Revival building, heads on up.

Now, three Greek Revival buildings will face out onto the Founders Monument in the middle of downtown Bridgehampton.

As for the southwest corner, well, the town did buy a quarter-acre behind the shops there and named it Militia Park. It’s something.

I can hardly wait to see this northwest corner completed and joining up with the Topping Rose House, which, on the northeast corner, is a thriving example of what can be done with an historic building. I also can hardly wait to see the Nathaniel Rogers House Museum on the southeast corner finished.

Now if only we can get the lighting company to put all the telephone lines underground for these four blocks of Main Street. It should not be so costly. It’s not that long a distance. And did you know that back in Montauk, realtor and businessman John Keeshan and others spearheaded a drive not too long ago to have the power company take down all the utility wires along that Main Street? Yes, they did.