By the Book: How Radical Was Linda Coleman’s Descent?

It’s a clever title that Linda Coleman has given her memoir, Radical Descent (Pushcart Press), though she credits a friend for suggesting it. Subtitled “the cultivation of an american revolutionary” (lower case intended), the title plays on the similar sound of two words whose meaning ordinarily would not be linked—“descent” and “dissent.” As Coleman recounts her deepening involvement with an obscure Weather Underground-type guerrilla cell centered in Portland, Maine, she says she felt herself “descend” into a world that both attracted and frightened her. Her ambivalent feelings were determined as much by the sexual magnetism of the cell leader, Roland Morand, as by ideology.

Though anyone can Google the names of Coleman’s cell members who were put on trial for sedition in 1986, her decision not to reveal names in her memoir works because it imbues the real-life figures with fictional status, making them characters in a kind of morality tale. By recreating events and dialogue, Coleman looks to create distance to explore motive and behavior from memory, her friends’ and her own. As she says repeatedly, especially as events accelerate toward violence, she felt confused. She wanted to be a “sister,” but she also wanted out. The memoir thus is not so much a recounting of what happened to her it is as an attempt, years later, to understand why. It took her 15 years to arrive at her theme, which is that improving society is essential, but violence is not the way. She also acknowledges that she may have been writing out of unease at how she treated her privileged but caring parents, members of the very Long Island one percenters (“old money, descended from “robber baron millionaires”) her cell thought they should bring down. The book is dedicated to her mother and father.

Coleman writes well and gives thanks to her mentor, the late Peter Matthiessen, who encouraged her to write and also become a Zen monk. He called the finished product courageous and painfully honest. It’s easy to see why Bill Henderson, the prize-winning publisher of Pushcart Press, chose the book for Pushcart’s 2014 Editor’s Book Award and why it has gone into a second printing. It makes for nonstop reading even though the theme is finally not persuasive. If so-called idealistic ends do not justify violent means, what does the epigraph from John F. Kennedy mean by “Those who make peaceful revolution impossible will make violent revolution inevitable?” What is “peaceful revolution” and who decides this? The era was seductively perilous, and many who embraced Marx, Mao or Che never recovered. FBI and KKK “death squads” may have been abroad in the land, but Coleman elected to fight fire with fire, or at least flirt with the idea of being “a revolutionary, a revolutionary woman” who might “give up everything to fight evil, to bring to reckoning the greatest evildoers in the world, to further the cause of peace and justice for all people.” Significantly, though the Weather Underground’s Bernadine Dohrn makes an appearance, Coleman’s guerilla cell seems to have been exclusively white.

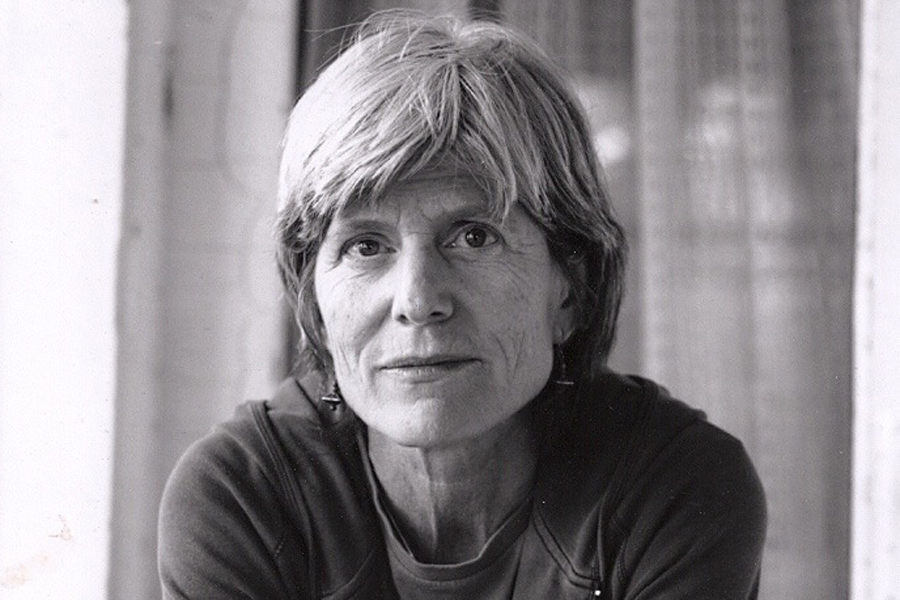

Coleman, now 61 and a resident of Springs, worked for many years as a nurse and a nurse practitioner and has been active as a leader of writing workshops for women in correctional institutions. She is particularly eager to work with young people and hopes that her memoir provides lessons.

The reviewer in The East Hampton Star complained that the memoir is too personal, not political enough. But Coleman’s ambivalent involvement is its fascination, especially as she missed some telling points. After her affair with Roland, she notes that he went back to his “former girlfriend” who, it turned out, was pregnant and far enough along that she could feel the baby kick.

One also senses that most of the young people Coleman would reach with her cautionary tale probably do not come from her blue-blood background and may not appreciate how she was able to avoid prosecution while others in her cell were sent to prison or fell into permanent despair. Coleman became a government witness in the sedition trial and had legal representation recommended by William Kunstler by way of her parents. She got off, even though she lent herself to buying guns for the group, driving a get-away car during a bank robbery and transporting explosives.

An intelligent, well-read and perceptive young woman, she made her choices, though in hindsight she says she was “dumb” and “naïve.” So, why would other young people feeling alienated in their home or social circumstances act differently? In any event, Radical Descent makes for an absorbing read about a heady time in American cultural history.