Jules Feiffer: Cartoonist Enjoys Remarkable Second Career

Jules Feiffer is one of the most celebrated cartoonists of his generation. He has won the Pulitzer Prize for his cartoons in The Village Voice. He has won an Academy Award for his screenplay for the animated film Munro, for which he earlier had written the illustrated cartoon book by that name. He’s been elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and in March he will honored for lifetime achievement by Guild Hall.

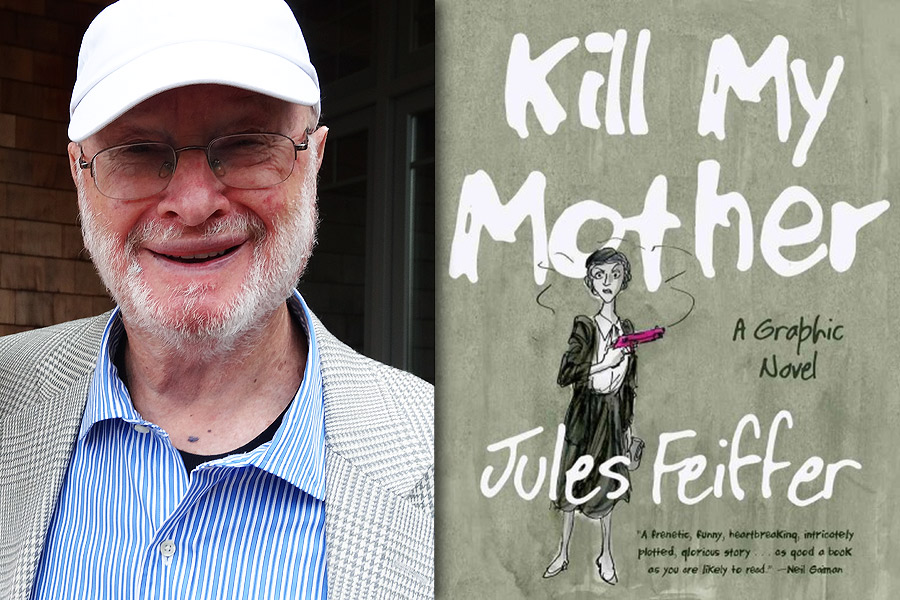

For the last 13 years, he’s also taught a course at Stony Brook Southampton Writing Arts Department called “Humor and Truth.” And finally, this year, at the age of 85, he wrote and illustrated a book called Kill My Mother that won a rave review on the front page of The New York Times Book Review and became a bestseller. Images and stories simply leap from his fertile mind. And they have been doing so since he was 6 years old.

Jules was born and raised in the Bronx, the son of a father who owned a series of clothing stores that, one after the other, failed. Those were the Great Depression years. Food got put on the table for the family by his mother, who worked from home as a fashion designer. She would design dresses, then take the designs down to the garment district in Manhattan and sell them to manufacturers there for $3 a design. She had a drawing table in the bedroom she shared with her husband. There was also a drawing board in Jules’ room.

It was on this drawing board that Jules did his first cartoons, emulating the drawings made of Popeye the Sailor Man, created by E.C. Segar. He had become fascinated with this work.

“I read the Sunday color supplements and the five or six column daily strips. They were a major form of entertainment in those pre-technicolor, pre-TV, pre-digital days,” Jules says. He was six. Popeye was full-page, in color, in the Sunday newspapers as a 12-panel cartoon story and daily as a single strip. Other comic strips were Terry and the Pirates, Flash Gordon and Prince Valiant. These were what kept kids going in those years.

When people think of cartoons today, what they mostly think of is what are called gag cartoons, a single panel that tells a joke. Jules fell in love with comic and adventure strips. He thought he wanted to write such things when he grew up. He never wavered.

Jules went to PS 77, two blocks away from his home, then to the James Monroe High School across the street. He was an indifferent student.

“I felt I didn’t learn anything in school,” he says. “I told them what they wanted to hear so that I could get my diploma and escape.”

He took the required art appreciation course. He liked to look at art and see what sort of emotional reaction he had. The course taught it the other way around.

“Before you looked at a painting, they insisted you learn everything about it ahead of time.”

In those years, the Depression years, everybody had an opinion. He had two sisters, the younger of whom survives. She had a career as a high school history teacher and lives in Huntington. His older sister, now deceased, was a full blown Stalinist. She and Jules had arguments.

“She was always quoting The Wall Street Journal,” he says. “The very thing she was fighting against. She denied the purges, the anti-Semitism, the show trials. None of those things were going on in the Soviet Union.”

Jules never went to college. He only had two in mind, Cooper Union and NYU in Washington Square to study cartooning. Both turned him down.

“I started looking around, hoping to be some cartoonist’s assistant. But those jobs were hard to find. Finally, I looked up Will Eisner, who wrote a comic book supplement that got inserted into newspapers. It was called The Spirit, about a crime buster who wore a mask. And no superpowers.

“Eisner had an office on Wall Street. He had his drawing board in the front office next to his secretary. The assistants worked in boards in the back, doing lettering, coloring, shading etc. I showed him my work, and he said ‘it’s lousy,’ so I began to talk about his work and how much I admired it, which I did. He was my hero. So he hired me as a sort of Eisner groupie. I became his comics-conversationalist in the office. I was 17.”

Jules stuck around. He could draw figures, but he had no sense of objects. When he drew a gun, he told me, it looked like it was made of butter. He needed to be proficient with a #2 or #3 brush and he wasn’t. But Eisner kept

him around.

“Looking for work I could handle, he tried me out on story. And lo and behold, I became the ghost-writer on ‘The Spirit’ for two years.”

Jules was drafted in 1951 just as the Korean War was winding down. He went through basic training at Fort Dix, then was sent to Fort Monmouth to a magazine unit that did army manuals. This was in New Jersey. He served two years, and on the side, with the permission of his superior, he began to draw a boy named Munro, who was 4 years old, but got drafted anyway. The army said he couldn’t be 4 because the army doesn’t draft 4-year-olds. And it went on from there.

“I had learned that if you wanted to make an editorial point, such as about the military mindlessness that held sway at that time, you couldn’t just come out and have a lead character spout it, you had to find a way to sneak it in around corners. A kind of sleight of hand. And being funny helped a lot. There were no Jon Stewarts or Colberts around then. They wouldn’t have been allowed on the air. This was the age of loyalty oaths and Joe McCarthy.”

Out of the Army at the age of 23, he returned to New York City, told his mother he would not be coming home, which made her sad, and then he rented a cheap apartment on East 5th Street between Avenue A and B (everything was cheap then, he says) and began to look for a job in an art studio where he could draw and also still draw at home.

“I found out there was unemployment insurance. If you could work for six months and get fired, you could collect unemployment for six months. So I’d do that. Six months at a hack art studio job, then do something to get fired, and then six months writing and drawing social and political satire that there was absolutely no market for. I did this for three years. I considered it my National Endowment Grant.”

Jules explains how you could live just fine then. “I was getting $20 a month from the Army. My apartment was $25 a month. I’d have the unemployment and I could go out with friends, have drinks, cabs and sometimes eat out at a restaurant, no problem.”

During this time, Jules wrote a series of long narrative cartoon books. Some you will be familiar with. They went on, in later years, to become best sellers. Munro, BOOM, Passionella, Sick Sick Sick. But not then.

“I took them around the city to publishers. All of them liked what I did, but they didn’t know what to do with them. They said I needed a name. They were all very encouraging.”

One day, Jules Feiffer saw a copy of a new local newspaper on the stand. It was called The Village Voice. He went down and met the editor and publisher, Dan Wolf and Ed Fancher. They loved his drawings. Everybody in the office loved them. They were offbeat and new.

“They went nuts. They wanted to hire me on the spot. I asked, what do you want me to do? They said whatever you want. The thought terrified me. I wanted an assignment. I would be on my own.”

Feiffer thought that maybe it would take three years to get well known. It took three months. He became famous.

“My drawings were political, social and sexual. Nobody was doing this. I wrote and drew the subtext of what readers thought but were scared to say. This was in the straightlaced 1950s.”

“They didn’t pay me a penny for my first eight years. But I was being published. I discovered freedom. But now I had a choice to make. I could look for more success and money. And yes, I wanted those things, but what I had was more important. I was doing what I wanted to do. I thought—screw the money.”

Jules would do his panel in The Village Voice for the next 42 years. In the meantime, he also wrote screenplays and books, more than a dozen of them, collaborated with others, wrote the play Little Murders, and another called The White House Murder Case, wrote a novel called Harry, the Rat with Women, and wrote the screenplays for Carnal Knowledge, Popeye and Munro. He won Obies and Outer Circle Critics Awards. He moved to the Upper West Side. He married, helped raise three daughters, became well known around the world, and then around 2000, at the age of 71, he began to wonder if anything he was doing mattered.

“It was during the Gore-Bush presidential election. I had thought all this time that what I did made a difference. Now I thought, the politics, the president—it all leads nowhere. Bush or Gore, what’s the difference. I have to make a change for myself.”

In other words, it was no longer fun.

Fortunately, as Jules now sees it, he was fired from the Voice. They said they were over-paying him and wanted to cut back, Jules says. He had begun to write and illustrate children’s books, and, along with playwriting and screenwriting, the weekly comic strip had not only ceased to become his major source of income, it had begun to lose his interest.

His leaving the Voice was front page metro news in The New York Times. And among others reading what was happening was writer Roger Rosenblatt, who was starting a creative writing department at Southampton College. He called Jules up.

“I want you to teach a humor-writing course at Southampton,” he said, “I’m not interested in your self-pity. I just want to know when does your health insurance run out?”

“At the end of the year.”

“You are going to come out here to teach. Anything you want. You will be paid next to nothing and you get full insurance coverage.”

“What should I teach?”

“I don’t care.”

“How often?”

“It’s up to you.”

“When do I have to start?”

“You’re beginning to bore me,” Roger said, and hung up.

Jules Feiffer moved out here three years later, he met the love of his life, Joan, who writes as J. Z. Holden, and they got a house in Northwest. He loved teaching his writing class, “Humor and Truth.”

“I told my students, ‘You have a license to fail. Play it safe, you won’t do well. Take chances, you’ll do better.’ I taught once a week, for three hours, anywhere from 10 to 15 kids. I get a lot of young people, a lot of older people, nearly all of whom had interesting stories to tell. They had burned out. Drugs. Divorce. Drink. Moved out here. Discovered or re-discovered writing and, to my surprise and delight, I knew how to connect with them. I was able to help them. It’s been one of the most rewarding experiences of my life.”

(Beginning in 2015, with “Humor and Truth” ending its run, he begins teaching “the Graphic Novel.”)

With his new life, Jules suddenly felt free to do exactly what he wanted with his work. And he found it – quite sensationally, considering the reaction – by going back to his roots.

“I rediscovered the form I loved as a kid,” he tells me. “It’s storytelling, noir storytelling in the mode of Hammett and Chandler. Like The Big Sleep, or This Gun for Hire or The Maltese Falcon.”

Kill My Mother is a 150-page book telling the story of two families of women caught up in a world of private eyes, Hollywood and murder. It takes place between 1933 and 1943, drawn in the style he adapted from his heroes, Eisner and Caniff, a style that Jules claims he was unable to master until he was 80. It is refreshing, sensational, vividly graphic storytelling and it has struck a chord with the American public. They thought he would just fade away? Not at all.

Eighty six now, there is another reason why he has taken to this form. He doesn’t hear very well. He doesn’t move so well. That makes it difficult to collaborate on writing plays and movies when it is difficult to hear the dialogue you wrote.

“But this, sitting at my board, I am the writer, the director and the entire cast of this movie—on paper.”

Also in this era he has penned Backing into Forward: A Memoir. He has another book called Out of Line: The Art of Jules Feiffer coming from Abrams in mid-May. And he considers Kill My Mother as only the first of a trilogy. At the present time, he is hard at work on the second of these action-adventure adult comic books, which is set in 1931 as a prequel to Kill My Mother. He should have it finished by next November. Then he will begin his third book, set in the early 1950s which is about the Hollywood blacklist era. It’s tentatively called Archie Goldman and the Decline of the West.

In the meantime, his book The Man in the Ceiling is being made into a Broadway Musical for 2016, produced by Sagaponack resident Jeffrey Seller, with a book by Jules and music and lyrics by the composer of The Addams Family, Andrew Lippa.

And then, as our interview ends, he tells me about his three daughters.

Halley, 30, has her play I’m Gonna Pray for You So Hard now concluding a sold-out run at the Atlantic Theater Company. Kate, his eldest, lives on Martha’s Vineyard and writes picture books for children, four of which Jules has illustrated. And Julie, at 21, lives and works in Larchmont, NY with her boyfriend.

A proud dad.

Jules Feiffer will be honored at the Guild Hall Academy of the Arts Lifetime Achievement Awards on March 9. An exhibition of his work will be on display from March 15–April 26 at the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill, which will also host a conversation and book signing with Feiffer on March 20.