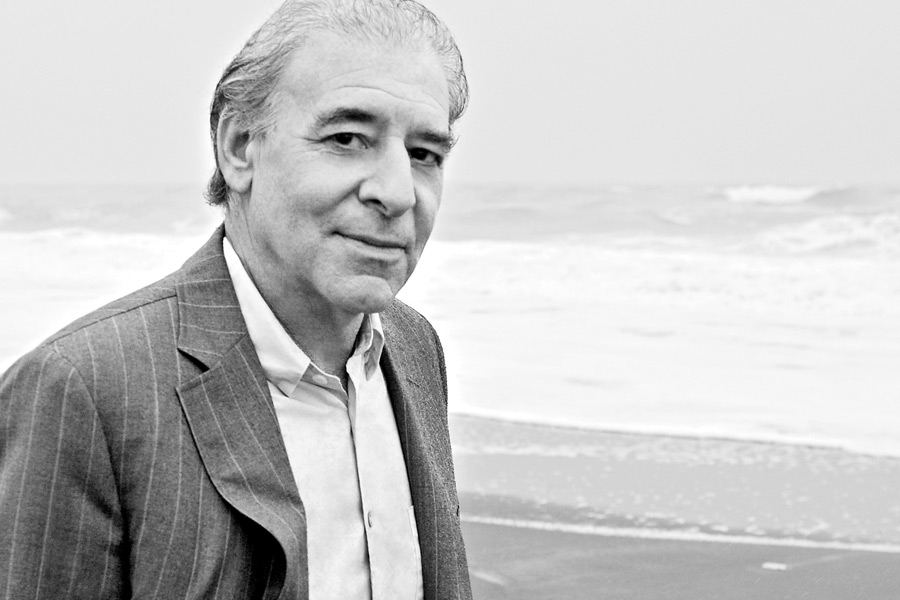

Who's Here: Alan Furst, Writer

Alan Furst, who has lived in Sag Harbor in a house on Hampton Street for more than 20 years, is one of the greatest writers of military war fiction in America. Some say he is the best writer of the years before World War II ever. This month the paperback version of his book Midnight in Europe comes out. Next year, his next book will appear and he will be off on tour once again. If you drive from East Hampton to Sag Harbor, you might hear him typing away, on an old fashioned 30-year-old typewriter, upstairs in his “office” where he looks out through the trees to the road. He keeps to a schedule. He writes about five pages of his book a day—about 700 words—he gives a first edit to 700 words he’s written on a prior day, and then he gives a second edit to 700 he’s written a few days earlier. The process takes him about three hours. Then he is done.

“Seven hundred good new words,” he says. “That’s about all I can do every day about words. Then I go on to other things.”

The other things might consist of “something not words” such as maybe TV, a trip into town to do some errands, dinner at Sen or the American Hotel or another good restaurant, then an evening out.

“I learned from my mother that I should always do my very best,” he says as we take seats out on his screened porch. “So that’s what I do. If someone says I think you can do better, I say, no I can’t. This is it.”

Furst’s books are about ordinary people doing heroic things. He finds them in a particular era in a particular place, in Europe between the year Hitler comes to power in 1933 and the year 1943 when it becomes apparent Hitler is going to fail, with about 30 million people dead.

“There is no middle in these years,” he says as we settle in on the sofas in his screened porch. “It’s good or evil. There’s just being on one side or the other and you are either a hero, a villain, a fugitive or dead.”

Furst has been telling me about his most famous book, The Polish Officer. It is three days after the Wehrmacht has begun its two-week march through Poland. It is just ten days before the Russian Army will attack from the other side. It is just two weeks away from when the Polish Army will collapse, and here is this Polish staff officer, holed up in his office, on the phone—the phones are still working—to say goodbye to his wife.

“How do you write about this time when everything comes crashing down,” I want to know. “All your characters are going to be dead.”

Furst grins. “Only some,” he says. “Heroic characters live to tell the tale and walk off into the sunset with someone they love.”

Truth is that many of Furst’s characters appear in more than one novel. The books provide a snapshot of Europe at this awful moment. Cities of great beauty, covered with smoke and fire. Ordinary people, challenged by events, who either rise to the occasion or fail. That’s how heroes are made.

There was a moment in his life—it was when he was 42 years old—that Furst suddenly realized that this was what he wanted to write about, that this was a driving force in him that he had to let play out. But perhaps it is best to begin at the beginning.

Furst wrote his first story, a story about two detectives named Frankie Gruvak and Lew Young, in pencil. It was three pages long. His mother typed it up for him. He was ten years old.

“Your mother seems to have been an important person in your life,” I said.

“She was a lion,” he says. “I was her cub.”

The year was 1948, the war had ended three years before, and he and his mother and father were living in a rent controlled four bedroom apartment on West End Avenue in Manhattan and everything was going okay. His father was in the millinery business, designing and making women’s hats. There was an office on 38th Street and a factory on 33rd Street. But the old country, the places where his parents’ parents had come from before, were devastated into rubble.

“I always wanted to be a writer,” Furst says. “I went to Horace Mann High School and had my own column in the newspaper. I went to Oberlin College in Ohio and became editor of the literary magazine there.”

He came home from college and went back to his parents’ house. His mother gave him $100. She was very nice about it.

“Here’s a hundred dollars,” she said. “It’s time for you to find your own place.”

For the next three years, Alan Furst worked as a Manhattan taxi driver.

“Tell me a story about being a taxi driver.”

I don’t mess around with good storytellers.

“My first day on the job, they send me to Lexington Avenue uptown which at that time was a quiet part of the city. Everybody is waving at me, I think, what’s the matter, are my headlights on or something? Then I realize they want me to stop to have a ride. So the next one, I stop. He’s a quiet man in a brown suit, and he tells me to continue on down Lexington Avenue and drop him off ten blocks further along. So I do that. My next fare is a heavyset, loud salesman type fellow and he gets in and he says ‘You taxi drivers must have some great stories to tell, tell me one.’ So I tell him the only one I know, which is that there’s this quiet man in a brown suit who has me drive him ten blocks down Lexington Avenue.”

“That’s it?”

“That’s the only one I had,” he says.

After three years of this—and he tells me the story of the time at 3 a.m. one New Year’s Eve when there are no cabs to be had, so six people hail him and three sit in the back, one sits next to him and two sit in the trunk—he makes the decision to get out of New York City—and move out to the country. He goes back to school at Penn State in Pennsylvania and gets a Masters in English.

“The trunk wasn’t closed, was it?”

“It was open.”

It’s here at Penn State that he meets the woman who is to become his wife. Karen is 18 and taking a class from him. (Ph. D. students teach undergraduate classes.) He’s 28.

“I know there is a rule that you don’t run around with your students, and I had always respected that, but this was different,” he says. “It was love at first sight. She handed in her exam book at the end of the term—and I reach over and take it. I ask her to come over tonight. She says she has a date. Break it, I tell her.”

This is in 1969. Crazy things are happening in America in 1969. Woodstock, for example. The whole hippie culture.

“It was like in a movie. She comes out to the farm where I had rented this cottage, and I take her to the Lewistown State Fair that evening, but the fair is closed, it is not going to open until the next day. All the workmen are working on the rides. I find a man working to set up the roller coaster and give him $5. ‘How long can we ride on it for $5 I ask? ‘Long as you want,’ he says.”

They get married. And they go to Woodstock.

“We were the first people to leave Woodstock,” Furst tells me. “We drove in from the west, there’s no traffic on the roads at all, we get there, we find a place to park where there is a cop, and we climb this hill to listen. The field below is filled with half a million people. Not many facilities. It’s a mess. The helicopters are buzzing overhead, we can’t hear anything. We decide to leave.”

“Did you hear ANYBODY?”

“We heard Richie Havens. I think. So we get to our car, and the cop is there and he says good thing you are leaving, the big storm is coming and everything is going to covered in mud. These cars will be sunk into the mud up to their side view mirrors. They’ll be stuck for a week.”

The following year, Furst gets a Fulbright, and with the money he moves to Sommières, France, a village near Montpellier. He teaches at the University of Montpellier. After that year, he’s offered a full-time teaching job at Montpellier, but he and his wife decide to return home.

“But not to New York,” he says. “Seattle.”

“Why Seattle?”

“I wanted to get away from that whole East Coast mentality. ‘So, what do you DO,’ that mentality.”

In Seattle, back then, you work for Boeing,” he says, “or you don’t work at all. This is before Microsoft. I couldn’t get a good job. I got odd jobs. At one point I worked for a year at the company of a man who had gotten a government grant to help poor people find jobs.”

During this time, Furst gets an agent and his first book is published. It is just a plain old murder mystery called Your Day in the Barrel. It is a complete flop. He calls a sales rep friend to find out how it sold. The rep says, well, it’s sold a few more books than one of the other books in this group anyway. What’s that book, he asks. It’s a cookbook called First You Take a Leek.

It sold 800 copies. Furst finds an agent, but his next book also flops, as does his next. He writes about the Caribbean, about Paris, and that’s because his agent has set him up writing magazine articles, mostly travel magazine articles, which after trips to interesting places around the world appear in Esquire, The New York Times, Elle, Salon, New York and even the Seattle Weekly. He and his wife leave Seattle and buy a house on Bainbridge Island, which is between Seattle and the Olympic Peninsula—a house that sets them back all of $19,000.

In 1983, something very traumatic happens.

“I had been sent to the Soviet Union by Esquire. It was horrendous. I was followed everywhere. People were terrified. There was little to eat. The whole country was being run by the Secret Police. We came home, and landed at LAX. I got down on my knees and kissed the ground of the United States of America. And from that moment, I knew what I needed for my books to be about.”

“What was that?”

“I looked to see if there were anyone writing about the rise of Hitler, and I couldn’t find anyone who was doing that in the way I wanted to do it. My next book simply flew off my fingers. It was about Europe, not about England, not about America. It was a book filled with Russians, Poles, Hungarians, members of the NKVD, and I felt as if I had fallen down a rabbit hole. We moved to Paris.”

The book was Night Soldiers and the start of a new career. The pair rented a two-story duplex atop a Hotel Particulier on the Rue de Park Royale. They were to remain there, with Alan writing Dark Star, another in the series of spy novels, and Karen enjoying great success as a landscape architect for the American firm Kaufman and Broad, for the next nine years.

“In 1993, it was time to come home,” Alan said. “We moved to Sag Harbor.”

“Why Sag Harbor?”

“We had been told it was very beautiful and very quiet and it is both those things. It’s a village where people know one another. And in Sag Harbor, we were nearby to the Hamptons where one could go to fundraisers and parties, which I had no desire whatsoever to go to. Once I went to one. Also it was near New York City, the center of the publishing industry. When I was in Paris, I was aloof from publishing and publishing was aloof from me.”

Furst’s next book, The Polish Officer, came out in 1995 and was another critical success. From that day to this, he has written 11 more books about this era, and many characters, as I have said, jump from one book to another. He has a huge following. And he travels when the books come out all over.

All of them, beginning with Kingdom of Shadows in 2000, have been a financial success in addition to a critical success.

“It’s set in Hungary during the war. And it’s based on a true account. For a long time during the war, there was a group called ‘The Shadow Front,’ which put itself forward as a small splinter group, but practically everyone in Hungary was in on it. Royals, conservatives, Jews, intellectuals, Communists, labor. It was led by Admiral Horthy. Actually it used Admiral Horthy.

“Touring is not easy. It’s tough. The book readings are fine and I enjoy that part. But even though I fly first class, stay in first class hotels, have a car waiting and all, it’s a grind.”

Leaving Furst’s home, I felt I had met a man who had found exactly what to do in his life and was now going at it full steam ahead. Right here in Sag Harbor.