A Fluke: 17 Years Later, DEC Sent Him $1K for Some Fish

Last week, bayman Stuart Vorpahl of East Hampton received a check for $1,000 from the State of New York. It was payment, without interest, for some boxes of fish that had been illegally confiscated from him in 1998. Imagine waiting 17 years to get paid.

This long-ago battle was about whether he’d had a fishing permit when he caught the fish all those years ago. In 2003 a judge ruled in Vorpahl’s favor. So here, in 2015, was the check.

“Lawyer Dan Rodgers told me it would be coming,” Stuart said. “He represented me. He also represented Kelly Lester and her brother Paul after a DEC official illegally confiscated fish for sale in an ice chest in Kelly’s front yard five years ago. He said this check would make me happy.”

“What are you going to do with it?” I asked Stuart.

“We’re still deciding which part of the South of France we want to go to,” he said.

“What part of the State of New York is the check from?”

“It’s from the State of New York Department of Environmental Conservation.”

“Who signed it?” I asked. “The Governor?”

“Some woman, Mary E. Balooski or Baloski, I can’t read the writing. And the whole check is handwritten, which is odd. Computers usually fill out checks from the government. This one arrived in the mail.”

“Is there something where they write what the check is for?”

“Sure is. It says ‘Settlement for Ent. Case.’ Must be entire case.”

“It was a big case?”

“Oh yeah.”

Stuart told me the story. He’s been a bayman for the last 40 years. He has a license to fish. It comes from Thomas Dongan, the English Governor-in-Chief of the Province of New York. In 1686, Dongan, after getting an approval from the King, issued a patent giving the residents of East Hampton the right to fish all the bays and lakes and rivers in the town without interference from any other authority. For 330 years, it has been honored as a fishing license and it has survived numerous legal challenges. Vorpahl keeps a copy of the Dongan Patent in a clear plastic sleeve he keeps tacked to the dashboard of his fishing trawler The Polly and Ruth. He’s had it there 21 years. When authorities come around, he shows them the Patent. On August 14, 1998, he was standing on Town Dock next to his boat, getting ready to go home, when he was approached by Joseph Billotto, an enforcement officer for the DEC who said the fish next to him on that dock had been caught illegally. The State of New York had passed a law requiring commercial fishermen to pay to get a permit to fish in the ocean. Vorpahl, who knew this drill, showed him his “permit.” He thought that would be the end of it.

It wasn’t.

With that, Officer Billotto gave Vorpahl a summons, took photographs of the fish boxes and then confiscated them. He loaded the boxes in the trunk of his vehicle as “evidence” and drove off.

Vorphal was arraigned before the court on the charges of not having a license and therefore illegally possessing fish he’d caught, and he pleaded not guilty. The matter of the State of New York vs. Stuart Vorpahl therefore came up in the East Hampton Town Court before the local judge there. Witnesses were called. Testimony given.

Vorpahl gave me a good account of how that went. He remembered it well. He’d had a lawyer. He said the fact there were fish on the dock didn’t prove they came from his trawler. Other fishermen testified that those boxes were props that the DEC enforcers had set there to pretend to catch people fishing illegally and they had seen them before. Billotto testified that earlier he had seen Vorpahl loading the fish, which were fluke, into his trawler “a half-mile north off Culloden Point heading for the breakwater,” but there were also fishermen who testified that at the time Billotto said in his complaint he’d seen Vorpahl loading fish, 11:30 a.m., in his boat a half-mile away from just off Culloden, they’d seen him in his trawler further east. Still others testified you couldn’t tell a fluke from a striper a half-mile away from Culloden Point. And still others testified that no commercial fisherman in his right mind would fish off Culloden, because the bottom is rocky and it would tear up the nets. And then Town Harbormaster Ed Michaels said he too saw Vorpahl elsewhere at 11:30, and he was not half a mile off Culloden.

The judge in East Hampton declared a mistrial because of all these discrepancies, and a few months later Vorpahl discovered that in the new DEC petitions asking for a re-trial, Billotto was now saying he had seen Vorpahl fishing in Fort Pond Bay, one mile west of Culloden, where the other fishermen said they had seen him. He had actually modified his report. As a result, Vorpahl wrote two letters, one to the Chief of Investigations and the other to the Administrator of the State Commission on Judicial Conduct, detailing what he said was tampering with the evidence. He never received a reply. Vorpahl also said that some of what the court stenographer had written down was no longer there. For example, Harbormaster Michaels’ testimony was not in the transcript. He also said that his lawyer had told him that the State, in asking for a re-trial, had not listed a proper cause to do so in their application.

The entire local East Hampton fishing community had so rallied to Vorpahl’s defense that no further trial could ever find Vorpahl guilty of any supposed crime in this matter. The DEC would not give up, though. They asked that the matter be adjudicated in a courtroom in Riverhead, where they said a jury not prejudicial to the defense could be found, but Riverhead lawyers for the State said that Riverhead, also full of fishermen, would also be prejudiced against the State, and so that went back and forth with new paperwork for a while until, in 2002, it went before Judge Tom DeMayo in Southampton.

As a result, after hearing everything, Judge DeMayo threw the case out once again, this time “in the interest of justice.” As a result of this, financial retribution needed to be paid for the fish that was seized.

So here it was, last week, many years later, that a check for $1,000 from the DEC arrived in the mail, finally putting an end to this case. Vorpahl and I discussed it further and we came to think that the files of paperwork must have gotten so big with all the backing and forthing and running around that stuff had gunked up in the wheels of the check-paying department, which could not find the paperwork authorization requiring them to send a check.

“Does it say anything else on the check?”

“It says it was issued by the DEC’s ‘petty cash’ account.”

“Aha.”

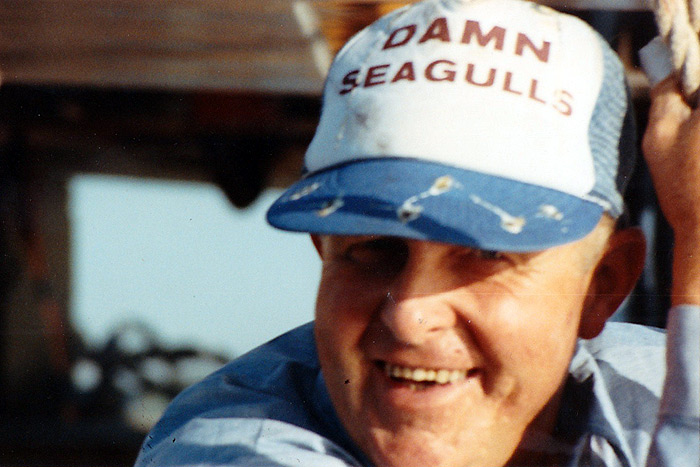

Stuart Vorpahl is now, in his mid-70s, retired from fishing. He sold his trawler. He does engine and boat equipment repairs and other things in retirement.

I talked to Stuart about another run-in that I thought involved the DEC about 10 years before that. But the DEC was on their side on that occasion, Stuart told me.

“It was about pollution and the perpetrator was General Electric,” he said. “They had a chemical plant upstate and had been dumping PCBs into the Hudson River for years and years and the stuff had gotten into the striped bass, which meant if you ate stripers you got poison. This seriously interfered with our fishery out here. There were four or five years the fish were poisoned. We couldn’t sell the catches. As a result, General Electric was required by the DEC to pay us restitution for the money we would have earned if there hadn’t been any PCB problem. As I recall, each of us fishing families were entitled to about $35,000, for the four years. All we had to do was produce paperwork to show our income from the year before the ban went into effect and they would calculate what was owed. For me, though, they didn’t.”

“What do you mean?”

“They didn’t like my bookkeeping system. Just about everything I caught—my dad did this too—went to the fish market. We’d attach a card to every box and the market would sign for it and write the amount they were paying for it on the card. I saved all my cards. Had them from every year. But the DEC didn’t like the cards.”

“Did you ever get paid?”

“The DEC decided that those who didn’t have acceptable bookkeeping would get $5,000 from GE per family. So I got that.”

“Was it true that years later, the IRS came in and accused the baymen of not paying income taxes on what they got from GE?”

“It was. I wasn’t one of them, though. I’d always paid my taxes. And I thought the $5,000 from GE was income, so I paid taxes on it. But others considered this as something other than income. It was compensation for lost wages. So they didn’t pay taxes. And the IRS caught ’em. A year later, though, I got a call from some man saying he was from the IRS. He demanded I pay taxes on my $5,000. I told him I already did, and I didn’t believe he was from the IRS, but if he was he should call me back, and then I hung up. He did call back. And I sent him what my proof of payment was and never heard further of it. He was from somewhere in Idaho.”

We talked about a current problem with the fishing. “It’s all bunker fish this year,” he said. “It’s been a terrible year. That’s all that’s out there. You set a net, an hour later it’s filled with a ton of these bunker fish. They also call them Menhaden. They’ve taken over. Never have seen anything like it. It’s got something to do with the environment, for sure, that all that’s out there is these bunker fish.”

I told him I’d seen schools of them this summer in Three Mile Harbor when I walked my dog at night. By the harbor lights, you’d see them underwater, all shiny silver colored, moving in schools together as if they were one organism. And I hardly saw any other fish.

“This August, a boatman up in Peconic Bay said over the marine radio they were tracking the biggest school of bunker fish they’d ever seen. It went on and on. In the end they measured it as a mile and a half in length. Imagine that. Millions and millions of bunker fish heading out to somewhere because there’s no market for them and we can’t do a thing with them.”

I wished Vorpahl and his wife a good vacation in whichever part of the South of France they decided upon, and we went our separate ways. It’s always good to see him and hear what he has to say.