Stuart Vorpahl: A Bonacker Who Saw Something Wrong, Wanted It Right & Didn’t Quit

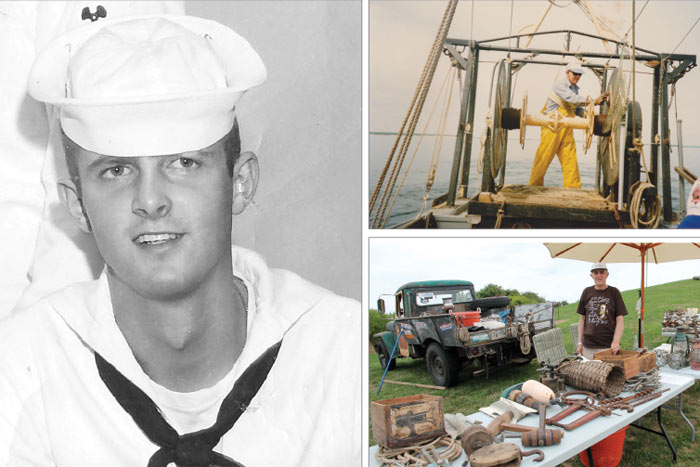

Stuart Vorpahl, a bayman, passed from the scene last week at the age of 76. He lived with his wife, Mary, just off Three Mile Harbor Road in Springs, the historic home of the Bonackers, just a short walk to where he kept his boat. He fished, he clammed, he was a loyal friend, he told stories and he fought for the rights of these people, the Bonackers, who are the descendants of the first settlers, the working class of English people who came here when Lion Gardiner founded this place in 1639.

Vorpahl kept a copy of the Dongan Patent—the document from the King of England describing the rights to the bays and beaches of the East Hampton Townspeople in 1686—in a plastic sleeve tacked to the wall of the cockpit of his boat. He never bought a state fishing license. When asked for one by a maritime patrol, he would take out the document and show it. The town had been established when it was written. It never had been overturned. Usually, the authorities would go away.

But sometimes they didn’t. About three months ago, Vorpahl received a check from the State of New York Department of Environmental Conservation for $1,000. The State keeps a fund where they can send out amounts where they think they are due. So it came from there. Why? In 1998, Vorpahl’s property—some lobsters and fish—was seized, but the matter was thrown out by the courts after an appeal two years later. He was entitled to payment for what was seized. But it was never sent. There was a bureaucratic mix-up.

For years and years, since that time, Vorpahl, among others, had fought vigorously up in Albany to have these failures to pay for what was illegally taken by the state not be subject to a “bureaucratic mix-up.” They happen all the time. In fact, there is almost no occasion where stuff is paid for. It’s a scandal and is not being fixed to anybody’s satisfaction.

I asked Vorpahl what he would do with the $1,000 when I last saw him. He told me he was taking Mary on a trip to Paris for a month.

My guess is he has held on to that check, never cashing it. And now he’s gone.

Vorpahl was not alone in fighting for the Bonackers. On the other hand, it was he I met when I wrote a story about the Bonackers and the Dongan Patent.

It happened very dramatically about 15 years ago. One afternoon my front doorbell rang. I answered it, and there stood a man I had never seen before, holding a copy of my newspaper. I invited him in.

“Let’s go over this line by line,” he said as we sat down in the living room.

Two weeks later, I published a new article. He didn’t stop by this time, but he called. “You got much of it right, but not all of it,” he said.

“What’s still wrong?” I asked.

“I already told you,” he said. “Go over it again.”

Thus began a friendship between he and I. He was my research. We ate at Michael’s Restaurant up in Maidstone Park, he and his bride and I. I went to his house, he came to mine. We lived less than a half-mile down the road from each other. He gave me a broken fishing rod to put on the roof rack of my Tahoe so it would look like I was going fishing when I went out onto the beach to write a story, something I liked to do. I had told him I don’t fish. Good, he told me.

Vorpahl had many, many friends. He had become the Town Historian after he retired from fishing. But he continued to be in and out of courtrooms, always fighting for Bonacker rights. He was at Town Hall speaking out to urge the town to protect the old ways from the new.

One night, driving home from work, I encountered him in waders in Town Pond in East Hampton along with five other Bonackers, their dogs, a rowboat, a boom box radio, clam rakes and bushel baskets. I stopped and took pictures. At the behest of East Hampton Village, they were cleaning the pond bottom of algae and other junk. The night I was there, they came up with a bicycle. Who pedals a bicycle into a pond?

Vorpahl was good natured, friendly, determined, interesting, funny and he always looked you straight in the eye when he spoke to you. I don’t know anyone who did not like him. (But then I don’t know the code enforcement people).

One of the family members called me the day he died. I told her I would surely miss him, and she said you most certainly will. She told me there would be a service for him and she would let me know, but where she was reaching me was out of the country—we had just arrived for vacation and I could not come back for it.

I hope The Sag Harbor Express will permit me to quote from their pages the account written by Kathryn G. Menu about what was said at his service at the First Presbyterian Church of Amagansett. The place was packed.

Daniel Rodgers, attorney: How many people do you go through your life and they don’t need a last name? You think about Napoleon, Gandhi and other people, and then, of course, Stuart…. He was a man of letters, so well read. Mary always told me he started at the end and wrote from the beginning. And that tells me he was a man who knew where he wanted to go, he just had to find a way to do it.”

Supervisor Larry Cantwell posted this online: “[He] was a fierce defender of the rights and traditions of the common people of our town. He could spin a tale and recite history at will with a good sense of humor while making his point.”

Stuart Vorpahl is survived by his wife, his two daughters Susan and Christine, five grandchildren and one great grandchild.