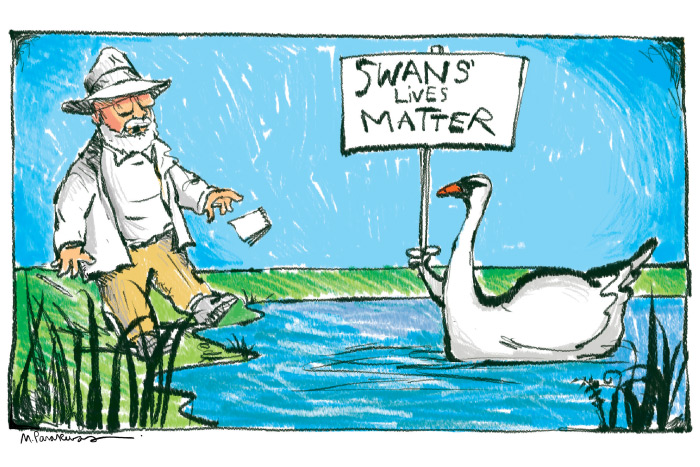

Mute Swan Speaks: Hamptons Swans Willingly Return to Belgium

Last week, I drove down to Town Pond in East Hampton to visit the beautiful white swans that swim around there. A law was passed in New York State last year that will make the swans illegal in this state. All of them are to be killed. This will be done a little at a time. By 2025, there will be no more mute swans in the State of New York. Hunters will get them. I parked my car by the side of the pond. There were four swans paddling around. Then one of them came toward me and—this is hard to believe—began to talk.

“Psssst,” he said. “Hey you.”

“You’re talking!”

“We can’t remain mute any longer,” he said.

“So you know?”

“We’ve heard of the plan.”

“I’m really sorry,” I said. “A lot of us fought against the new law. The DEC says you are an invasive species, brought here from Belgium in the 1890s to paddle around the ponds of rich men’s estates for their viewing pleasure. But you drive off indigenous birds and small animals. You take over.”

“I wouldn’t call it that.”

“We called our state legislators. We wanted you left alone. They wrote up a bill that would have modified the new law and allowed you to stay. But Governor Cuomo just vetoed it. I feel bad.”

“I’m speaking for the others.”

“What do you have to say?”

“I want to say it was never our intention to come here. In Belgium, our ancestors were rounded up and taken to America against their will. We were a happy group in Belgium. The weather was milder, the summers longer, the people friendlier. Here, everybody’s rush-rush, the people doing something. We will be happy to go back to Belgium.”

“What are you talking about? You are not being returned to Belgium.”

“Antwerp is my ancestral homeland. My family remains there. We now have a branch in Brussels, and in Bruges. We get postcards. Wish you were here. Pictures of the tulip festival or the Ghent University Botanical Gardens on the front. We’ll be happy to go back. And you shouldn’t feel so bad about it.”

“You’re not listening to what I said.”

“Look. We were brought here illegally. We have no papers. That was not our fault. We don’t want to be where we are not wanted. But we are in some kind of limbo. I’m told they want to build a wall.”

“There is no wall.”

“No wall is necessary. We’ll go peacefully. We’ll need a little time to pack our bags.

We’ll go.”

“Who told you that you were going to Belgium?”

“A man from the DEC was here. Two men. They were talking. We heard what they said. We are a proud people. We will go, our heads held high, tail feathers wiggling, our webbed feet marching us along.”

“To where?”

“To the ships. At the docks in Brooklyn, where we get on the ships going to Belgium.”

I just didn’t have the heart to tell him the true plan.

“So you came down here to say goodbye I guess,” he said, “and I salute you. Yes, I am talking to you. We salute you. We all salute you.” He pointed with one of his wings to the others. “Vaya con dios, as we say in Belgium.”

This is just so sad. The plan is not to take anybody back to their homeland. The plan is, slowly but surely, to hunt them down and kill them off. Take away their eggs. Throw blankets over the heads of some of the swans—we’re not all evil—and take them by truck to New Jersey or Connecticut and let them decide what to do. As for the others, if we can’t catch them, we call in the hunters to give the coup de grace, so to speak, a snootfull of buckshot until they die.

The swan began singing. He has a deep baritone. Who knew?

“We shall overcome,” he sang. “We shall overcome some day. Deep in my heart, I do believe, we will overcome, one day.”

He sat down. And with that, another mute swan, this one a bit bigger, came out of the pond. His beady yellow eyes locked with mine. He waddled forward toward me, hissing.

The other swan got up.

“Junior,” he said, “get back, I’m handling this.”

But Junior didn’t stop. He came right at me and I ran for my car, hopping in and slamming the door just before Junior got to me. Junior began beating my car door with his wings. He pecked at the driver’s door. Then he was pecking at my tires rat-a-tat-tat.

“Junior, that’s quite enough.”

I drove off, slowly at first so to be sure I was not running over Junior. Then I picked up speed and headed down Main Street and away, up North Main, past the windmill and under the railroad overpass to Three Mile Harbor Road. I looked in my rearview mirror. I had escaped. Junior was nowhere in sight.

There was an announcer speaking on the radio.

“The Village of Manlius in upstate New York asked the DEC for a swan exception waiver for the beloved swan couple Manny and Faye in the Village Pond the other day, and it had been approved,” he said.

The DEC plan originally would have resulted in Manny and Faye getting hit with two shots of a hunter’s gun, but now the DEC will allow Manny and Faye to continue to live in the Village Pond, and, if they have cygnets, the cygnets can live there too, until March 2016. The public can watch them paddling around as swans do, the mother swan at the front, the cygnets in a cute little row and the daddy swan bringing up the rear until then. After March, the exception expires, but because they had an exemption, they will not be shot, they will be spared, and the mom and dad and cygnets are will all be rounded up in a gunny sack, put in cages and taken to Pennsylvania for a further public viewing for awhile, and then flown off to London, England.

“The swans displace native wildlife species, degrade water quality, threaten aviation and destroy submerged aquatic vegetation,” the announcer was saying.

Maybe I could get an exception for the East Hampton swan that talked to me. That’s pretty special, a mute swan talking like that.

I remember the last thing he said as I was driving off, not to me, but to Junior who was still strutting around on the edge of the pond.

“Can’t we all get along?” is what he said.

This whole thing is so sad. I wish that something could be done.