Explosion, 1844: Julia Gardiner Falls in Love with President Tyler

On February 28, 1844, the President of the United States, James Tyler, along with 349 other special guests, boarded the brand new warship USS Princeton for its inaugural cruise down the Potomac.

The Princeton was the biggest warship built for the American Navy to that date, it sported a 178-man crew and possessed the two biggest guns in the world, at that time, on the deck—one called the Oregon and the other, an identical gun, called the Peacemaker. The ship was also the first to be powered by steam engines using twin propellers. It could turn or stop on a dime. All in all, it was the pride of the Navy, and onboard that day, in addition to the President, were the Secretary of the Navy, the Secretary of War, the Postmaster General and numerous other dignitaries and congressmen, many accompanied by their wives and children.

One particular guest that day was the young daughter of prominent East Hampton lawyer David Gardiner. Julia Gardiner was 23, and she was there because the President had fallen in love with her. He had secretly gone to see her parents to ask for her hand the year before. But her parents had turned him down, President or no. He was 30 years older than she was.

But President Tyler was not giving up. And so he had invited her father to this party. And oh, bring beautiful Julia. The President and the members of the Gardiner family knew of this love interest. But no one else did.

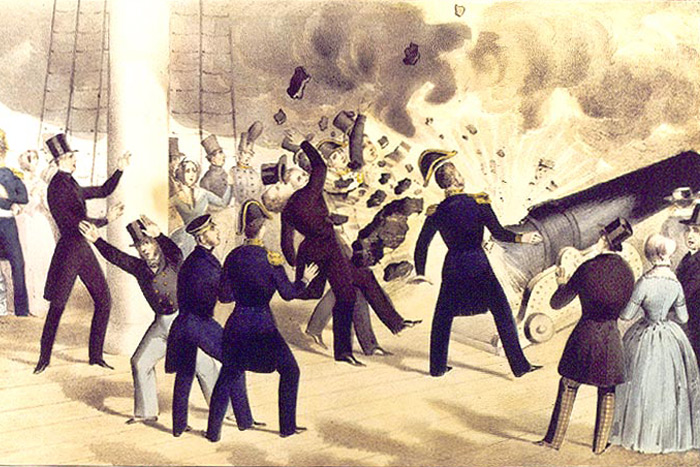

The Princeton glided down the Potomac with the party in full swing late that cold afternoon. A military band played. Food and drink were served on deck and below decks. After awhile, the partygoers asked the captain to fire the Peacemaker. He did. Then with more urging, he fired again. He fired at ice floes. The gun’s shells could go three miles.

With all this commotion and smoke, most of the women went below decks. Most of the men, though, stayed up top, asking for more, and for a while the captain obliged. Just offshore of Mount Vernon and turning around to begin to go back, though, the captain announced that was it—he’d fire no more. There were boos. The Secretary of the Navy, the captain’s superior, joined in asking for one more. And so the captain changed his mind.

The gun fired, but the shell exploded in the breech, shattering the Peacemaker and sending fire, smoke, bits of hot iron and wood everywhere. Eight people died, nearly all of them instantly. Seventeen were injured. Down below, the people started screaming.

Among those below just before the gun exploded was the President. He was down there with Julia. Moments earlier, when told there would be one last firing and he should go up to enjoy the finale of the gun’s performance, he started for the stairs, only to be sidetracked by a tipsy young man urging him to hear one of his college friends sing in the hallway. They were hoisting champagne.

Then came the explosion followed by the sound of shrapnel, iron and wood on the deck above. President Tyler raced up into the carnage of blood, dead bodies and the wounded.

Among those killed were Secretary of State Abel Upshur, Navy Secretary Thomas W. Gilmer, Princeton commander Beverly Kennon (who had urged this last firing), two sailors, diplomat Virgil Maxey, President Tyler’s personal aide, a slave named Amistead, and Julia’s father. Mr. Gardiner was not only killed instantly but, like others, his body was also torn apart. It was just an awful scene.

The President turned and raced back down below to tell the people partying down there what had happened. He also ordered everyone to stay there. After that, he had to tell Julia her father was no more. Julia fainted into his arms.

President Tyler remained below-decks with Julia for the rest of the trip. When the Princeton was fast to the dock, he carried her up to the gangplank, where, as he carried her across, she stirred. The two nearly fell into the sea. But the President regained his balance, and soon they were in the carriage and off to the White House.

A state funeral was planned for those who died. The dead in their mahogany coffins were taken to the White House, pending the funeral. Amistead, the slave, was in a cherry coffin. He is not mentioned as having been part of the state funeral.

Four months later, Julia and John Tyler eloped. They were married at the Church of the Ascension in New York City with just 12 witnesses, they honeymooned for a month in a cottage prepared for them at the Federal Fortress Monroe near Norfolk, Virginia, and then returned to Washington to announce their marriage to the public. No President had been ever married while in office before.

Before becoming President, John Tyler had been the owner of a huge Virginia cotton plantation he’d inherited from his father. He got married to his first wife, fathered seven children, then got interested in politics. He was elected a state assemblyman, then a senator and, finally, in the Presidential campaign of 1840, he was asked by William Henry Harrison, the Whig candidate, to be his running mate. Their slogan for the election was “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too.” Harrison had been an Indian fighter. And you also got Tyler.

Unfortunately, Harrison was the sort of manly man who, after winning this election, would give his long Inaugural address in front of the White House in shirtsleeves on a very cold January day. A few days later, he came down with pneumonia and died. And so, Vice President Tyler was now President.

Tyler had his first political fight with the cabinet of the late President Harrison. The members of the cabinet declared they would run the country. Tyler was just “temporary” President, a placeholder until a new election could take place three-and-a-half years down the road. Tyler would have none of this, and he accepted the cabinet holders’ resignations one by one, and said he would have the full powers of any sitting President—and he did. This became the model for future situations where a Vice President took over for a President.

During this fight, Tyler’s wife, Letitia, suffered a stroke and became bedridden. Tyler then received visitors in the Blue Room, accompanied by two of his daughters, Beatrice and an older daughter named Letitia.

At this time, as was the custom, kings, queens, diplomats and prominent members of the American social elite would be presented in a formal occasion to the President. As it happened, this coincided with some very bad and supposedly shameful behavior by the beautiful daughter of a prominent member of the American social elite, a businessman and lawyer in East Hampton, whose family owned Gardiner’s Island and whose immediate family, when not in East Hampton, lived in a mansion in Manhattan.

Julia Gardiner was born on Gardiner’s Island, educated at East Hampton’s Clinton Academy, and then, in her teenage years, at Madame N.D. Chagaray Institute for Young Ladies in Manhattan, where she studied French literature, music, ancient history, arithmetic and composition. In her senior year there, at the age of 17, she somehow arranged, on her own, to have a sketch of herself appear in a magazine advertisement for the dry goods and clothing emporium Bogert & Mecamly on Ninth Avenue in Manhattan. The drawing of her, escorted by a smartly dressed young man, had her saying “I’ll purchase at Bogert and Mecamly’s No. 86 Ninth Avenue. Their Goods Are Beautiful and Astonishingly Cheap.” This was the first time a member of the social set of New York had ever stooped so low as to do something like this. It was scandalous.

Julia returned for a time to East Hampton, where her biography says she studied piano and guitar, but then it was arranged for her, accompanied by her parents, to tour Europe until the outrage over her scandalous behavior had blown over. A steamship took them to England, France, Italy, Switzerland, Germany, Holland, Belgium and Scotland, and Julia was introduced to royalty and even got to kiss the ring of Pope Leo in the Vatican.

Before they embarked on this trip, however, they took a short trip to Washington, and it was there, before her “tour,” that Julia was presented to the President. He was immediately smitten, but he didn’t let on. His wife, disabled, was still ill and failing. She was to die within a few months.

* * *

Julia was the youngest First Lady until that time. She was also celebrated—something she encouraged. Immediately after marriage to the President, taking a train with him back to Washington, she could hardly fail to notice that the train platforms were crowded with people along the way who wanted to get a glimpse of her. Subsequently, her image could be found on postcards and in drawings and paintings in the magazines of that era. When she made an appearance somewhere, reporters commented on her clothing, her personality and even her skin. She went along with an engraving company’s request that an image of her be drawn by a popular artist and then be reprinted and sold around the country. The caption was “The President’s Bride.” She lent her name to songs and sheet music. One set of songs was “The Julia Waltzes.” On at least one occasion, she moved about Washington in a splendid coach being pulled by identical white Arabian horses.

And of course, she replaced Tyler’s two daughters as the Presidential Hostess at all functions. Letitia Harrison, the older, never spoke to her again. But all the other children of the late President Harrison accepted her.

Julia is credited with having a military band play “Hail to the Chief” to accompany the President wherever he went. She also arranged a new way of his meeting important people. Instead of entering a room and standing in the center to be surrounded by others, he’d stand along a wall and meet people as they came by in a line. Julia had seen this done in Europe. Julia also fought for, and eventually got, an arrangement where all Presidential widows would receive the continuation of their husband’s pension when he died.

John Tyler’s years in office were not great. He served just three years as our President, marrying Julia in that last year. During his Presidency, he did complete the annexation of Texas, a great accomplishment. He was not, however, a very good politician. Elected by the Whig Party, which opposed states’ rights, Tyler, as President, championed states’ rights. As a result, the Whig Party threw him out of their party—imagine that, a sitting President without a political party. Needless to say, when the time came for him to run for President in his own right, he declined. Without a party’s backing, he would lose.

It is not known if John Tyler and his wife visited East Hampton during the final eight months he was in office. But he did visit many times afterwards. The ex-President and his wife were part of the social set, and visited the summer resorts of Newport and Saratoga and East Hampton every summer for many years.

Also during this time, Julia worked closely with her brother Alex, who remained in East Hampton and became a power broker in Suffolk County. She helped him arrange a phalanx of politicians in public office who would be loyal to Tyler should he run for the Presidency in 1848 under his own banner, which he never chose to do.

Julia bore seven children with the President, all after he left office. While in office, she redecorated the White House, hosted many parties and, before the President’s term ended, held an enormous ball as a going away party. Some 3,000 people attended.

Fifteen years later, when the Civil War broke out, former President Tyler came down hard on the wrong side. A slave owner, he became a legislator in the Confederate government while it lasted. He died of various maladies in the second year of that war, and was buried under a small gravestone in a cemetery in Richmond, Virginia. But the country shunned him. It wasn’t until 1915 that Congress finally authorized the construction of an appropriate monument at his gravesite.

After Tyler’s death in the middle of the war, Julia went to live in the Confederacy, but after a time, still during the war, she moved to one of the homes that her late mother had owned on Staten Island. There, her home was raided one night by vigilantes who claimed, inaccurately, that she was flying a Confederate flag in her yard. Julia then left to take up residency at her late husband’s plantation for the rest of the war, enjoying the company of children and grandchildren who came to visit her. She remained there until her death in 1889, after which she was buried next to her husband in Virginia.