Not a Fun Job: Meet the Wreckmaster, the Man in Charge of the Cargo

Wheelwrights. Blacksmith. Cooper. Tinsmith. Lamplighters. I was flipping through some of the old town records at the East Hampton Library the other day and it struck me how many different jobs existed back in the early days of this town, founded in 1648. Shepherd. Yes, we had shepherds back then. They attended the sheep and cattle that were sent out to Montauk to graze in the summertime.

Then, I came upon wreckmaster. What the heck is a wreckmaster? I happened to be looking at the laws published for the year 1909 in the State of New York, and here in Article VII was an exact description of who the wreckmaster was, how he was appointed, what his powers were, how he was to be paid and even how he could be sued for damages. Being a wreckmaster was a New York State government job, a two-year appointment, and at the whim of the governor. I might add, it was a pretty miserable job, as you will soon see.

For the year 1909, there were three official wreckmasters in Brooklyn, two in Westchester, 12 in Queens, six in Nassau County and 15 in Suffolk County. There were so many in Suffolk County because, in the State of New York, that is where ships wrecked in greater numbers than elsewhere. Best to have the most wreckmasters on call in that county.

Here were the duties of the wreckmaster.

“Wreck-masters in the several counties shall give all possible aid and assistance to all vessels stranded on the coasts of their respective counties, and to the persons on board the same, and use their utmost endeavors to save and preserve such vessels and their cargoes, and all goods and merchandise which may be cast by the sea upon the land; and in performance of these duties they shall employ such men as they may respectively think proper; and all magistrates, constables and citizens shall aid and assist the wreck-masters, when required in the discharge of their duties.”

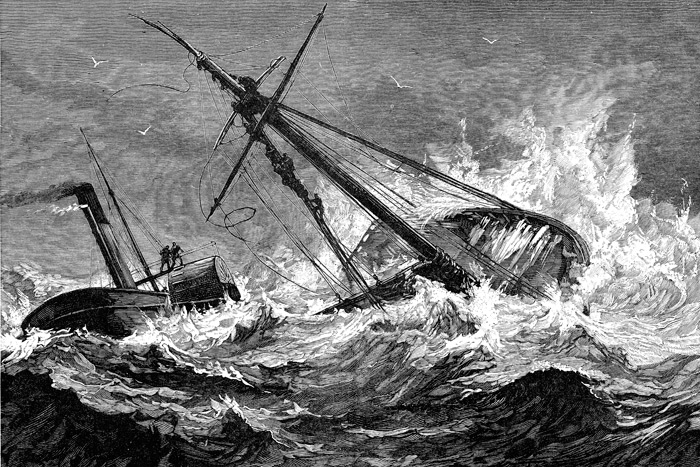

In 1909, and for years and years, and even centuries, before that, sailing ships wrecked on the shoals of eastern Long Island in great numbers. They came in during storms, they misjudged the coastline, they broke down, the captain was drunk—whatever it was back then, the ship would founder and in short order come on the rocks, with the cargo often floating ashore. Sometimes it was crates of whiskey. Sometimes it was furniture. Sometimes it was bolts of fabric. (For one 10-year period East Hampton women wore dresses made of brightly colored calico after one particular shipwreck. You’ll read about it below.)

Whatever it was, the local townspeople were the first to find out about it, and it was their job to report the arrival of the shipwreck to the constable and the local lifesaving crews down at the beach to rescue those onboard and the next thing to be done was to get everybody in town down there and haul away as much as possible to safety before the wreckmaster could get there.

This was tempting to do. During the 1850s, for example, the wreckmaster paid $10 for anyone bringing him news of a shipwreck he’d need to attend to.

“#81. The wreck-masters of every county in which any wrecked property shall be found, when no owner or other person entitled to the possession of such property shall appear, shall severally take all necessary measures for saving and securing such property; take possession thereof, in whose hands soever the same may be, in the name of the people of the state; cause the value thereof to be appraised by disinterested persons, and keep the same in some safe place to answer the claims of the persons entitled thereto.”

Somehow, from today’s perspective, I am imagining a man with a badge sitting at a desk in an office in Southampton or Sag Harbor and the phone rings and he says “Hello” and then “I’ll be right down there,” and then he heads out the door. But this was long before telephones.

“#8. All sheriffs, coroners and wreck-masters and all persons employed by them and all other persons aiding and assisting in the recovery and preservation of wrecked property, shall be entitled to a reasonable allowance as salvage for their services, and to all expenses incurred by them in the performance of such services, out of the property saved…and the salvage claimed in any case shall not exceed one-half of the value of the property or proceeds.”

What if the person who was to receive the cargo didn’t come out to claim the salvage for a long, long time? It stays stored in that safe place. Then, after a year, an auction was held, and the proceeds given (with the reduction of appropriate costs) to the County Treasurer in which the wreck takes place.

What if the cargo is bananas, or fish or other perishables? It all comes down to whether or not the receiver of the goods can get out to the wreck in a timely fashion. If not, the wreckmaster can take the cargo somewhere and sell it, then settle up with the late arrival.

Like I said, this is one thankless job. Life in the Hamptons back then was pretty much the same day to day. You’d go out fishing in the bay or out in the ocean. You’d plant crops in the spring and harvest them in the fall. You’d buy feed and hard goods at the store. You’d go to church on Sundays with your family.

And then there would be a shipwreck! Jeannette Rattray, a local woman who wrote for The East Hampton Star for over 50 years, wrote a splendid book about each and every shipwreck she could document containing chapters about every shipwreck on the eastern end of Long Island she could research. The book is called Ship Ashore!, and it covers the time period from the first settlers until the day she wrote it. She describes the scenes down on the beach. From the local people’s perspective, what they got was fantastic, exotic and remarkable. And there’s an old law of the sea stating that everything that washes up is yours. At least until the authorities arrive.

They would find a ship wrecked at the beach, the bells in the church towers would be rung, the people told to come down to the shore, the children in the schools let out. The wreckmaster, assisted by sheriffs, coroners, rescue workers and medical people, would arrive. According to the law, they were supposed to keep away those not meant to be there. Eventually, the people from the city with an interest in the ship would arrive.

Here are just a few of the shipwrecks that occurred on the East End during one 10-year period—1842 to 1851. As you see, this was a big deal.

In April of 1842, the French square-rigger Louis Philippe came ashore in Mecox. No lives were lost. The cargo was trees, dry goods and champagne.

A whaling ship called Plato came ashore at Montauk in 1842.

In March 1844, the brig Rebecca C. Fisher out of Puerto Rico bound for New Haven came ashore at the Shinnecock Inlet. No lives lost. Cargo was molasses and sugar.

In March, 1846, 100 Irish immigrants aboard the Susan came ashore at Southampton.

In December 1846, the brig Rolla, out of Salem, MA, and bound for South Africa came ashore in a storm, all its masts broken, at Canoe Place in Shinnecock. The crew was saved, the vessel and cargo were a total loss.

In March 1847, a vessel without a name came up on the rocks at Montauk on the North side. Six lives lost.

In 1847, the ship Ashland, with several hundred on board, came ashore in Southampton. All saved.

In November 1848, the cargo ship Ketchabonac foundered in Westhampton with a cargo of flour and corn.

On March 3, 1849, a ship broke up at Montauk, its name never known, and six bodies washed ashore. They were buried at Amagansett.

In June of 1841, the bark Henry, out of London, shipwrecked at Mecox. All on board, 104 people, were saved. The cargo, chalk and linseed oil, was a total loss.

And then on August 25, 1851, the Catherine, out of Liverpool, came ashore at Amagansett. Onboard were 300 men, women and children from Dublin, Ireland, bound for New York City and the immigration authorities there. All were rescued along with almost all of their luggage. They were taken to Sag Harbor, where another ship took them on to the city. The Catherine also had a cargo of iron, salt and soap.

Here are some other well known wrecks in these parts.

In the early morning of February 19, 1858, the clipper ship John Milton wrecked in a blinding snowstorm, coming ashore on the beach where downtown Montauk is today. It wasn’t until later that day that an old man, walking along the beach, came upon the wreckage of the bow with the ship’s bell clanging still on it. The rest of the ship was destroyed and the lives of all the crew washed up frozen that day and the next, 22 in all. A mass funeral service was held in the old white church across from where Clinton Academy is today, with the frozen bodies covered with linen stretched out by the pond. All were buried in the the graveyard there. Later the main mast of the ship washed up, and it is today the huge flagpole by the town pond. The cause of the wreck was a newly constructed lighthouse in Shinnecock. It had just gone into service, and the captain of the John Milton, in a storm, mistook it for the Montauk Light. He gave it a wide berth, but not wide enough, as he tried to negotiate through the storm around Montauk Point to the safety of Long Island Sound.

In January 1779, a battle between British Men-o-War and French Men-o-War warships began to take shape in Long Island Sound. The French were helping the Americans, the British were trying to put down the revolution. A huge storm came up and the battle never happened, but in the storm several of the warships were dismasted and one of them, the 74-gun British Man-o-War Culloden, floated onto a bar at Shagwong Point on the north shore of Montauk. The crew was able to get her off, but she beached again further west and is today an underwater wreck at what is now known as Culloden Shores. The sailors onboard waded to shore and made an encampment nearby that night, and then the next day returned and set everything above the waterline on fire. They didn’t want the French to get any of it.

Another famous, actually infamous, wreck took place at Mecox during a terrible winter blizzard on December 11, 1876. Coming ashore onto the rocks there was the ironclad schooner Circassian, carrying a cargo of furniture and fabrics. The 16-man crew was taken off safely as the storm subsided, but then the wreckmaster arrived, and after that an agent from the import firm in New York City, who wanted to try to remove the cargo by hiring a dozen Shinnecock Indians to bring it in. The Shinnecocks were rowed out to the ship, proceeded to load the cargo into small boats, and then waited there for the next small boat.

In the middle of this operation, a new storm, an ice storm, boiled up, and the agent, rather than have the Shinnecocks brought in to protect their lives, left them out there to make “one more load” of cargo into a promised last rowboat. The storm worsened, no new rowboat appeared and the Shinnecock men froze to death out on the wreck, one of the worst and most grotesque and completely avoidable disasters ever to befall that tribe.

The George Appold came up on the rocks just past midnight on January 9, 1889, a mile-and-a-half west of Montauk Point. It appeared that it might get off the next day but then a storm came up and wedged it in further. It broke up and its cargo of New England rum, shoes, boots, stockings, hats, underwear and bolts of calico floated ashore to be eagerly gone over by the local populace before the wreckmaster could get there.

The Elsie Fay wrecked at Ditch Plains Station on February 17,1893. The crew of seven was rescued. The entire cargo of coconuts floated in to shore and was feasted upon for months by the local populace. No sign of the wreckmaster.

And then there was the time in 1923 when the Madonna V shipwrecked at Montauk loaded down with some of the finest bootleg rumrunner Scotch made in, well, Scotland. And wasn’t that one fine day.

I don’t know when the job of wreckmaster went by the wayside. I suppose when reliable gasoline engines made crossings safer in the early 20th century, the state just voted this job title out of existence.

But that does not mean it couldn’t be made a job again.

Who knows?