Teddy Roosevelt: The Man Montauk Forgot

Few people know of the connection between Montauk and Theodore Roosevelt and the Rough Riders. There are two reasons for this. One is that Montauk is a wonderland of surfing, fishing, swimming, golf, tennis and resort living, and so there are many things to do that distract visitors and otherwise keep them from learning the remarkable history of this place. The second reason is that the deep Teddy Roosevelt connection—and lots went on here all those years ago—is not widely promoted.

There’s a condominium called Rough Riders Landing. And, for a long time, there was a Theodore Roosevelt County Park. But now, because in 2012 the County Legislature erroneously concluded that Teddy Roosevelt never stayed there, that park has been renamed. This same park is now called Montauk County Park. There is no longer even a hint that there might be something remarkable about this part of the town’s history.

Teddy Roosevelt was one of the greatest Americans who ever lived. That he spent a tumultuous month in Montauk and was visited by the President of the United States, the Vice President of the United States, the Secretary of War and several Congressmen to discuss his future is hardly known. This needs to change.

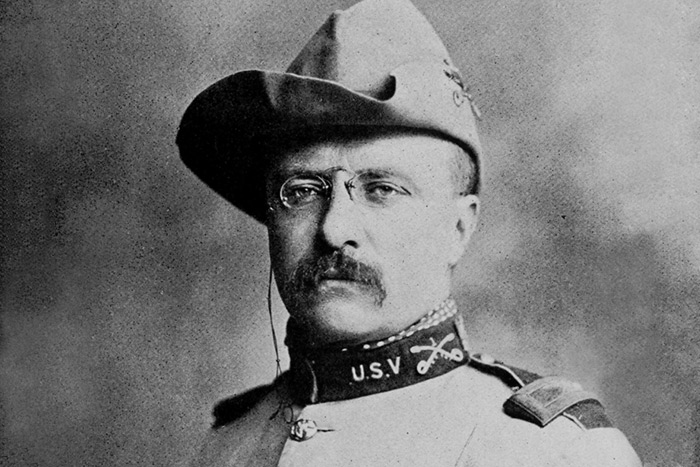

In 1898, when the Spanish-American War broke out, Teddy Roosevelt contacted some of his friends—nearly all either fellow Harvard alumni or graduates of other Ivy League Schools, members of elite private clubs or magnates from Wall Street—to create a cavalry unit of 100 wealthy young men called the Rough Riders. Roosevelt, then 29 years old, would lead them. The Rough Riders, along with the 35,000 other soldiers comprising the entire U.S. Fifth Army, were transported from Tampa to the beaches of Cuba early in the summer that year. The battle swayed to and fro as the Americans tried to drive out the Spanish, who had ruled Cuba for 400 years. Then, in one historic skirmish, Roosevelt and his Rough Riders charged up San Juan Hill on horseback, the Spanish fled and, soon thereafter, surrendered to the Americans in Santiago Harbor.

The victory was the first foray abroad for the United States. It marked the United States as a force to be reckoned with in the world and it made Colonel Roosevelt, whose dashing victory was splashed as headlines everywhere in the country, a true American hero.

The entire military campaign lasted 23 days. But now, with Roosevelt and his men and the U.S. Army living in tents up in the hills overlooking Santiago, everyone had to wait for a peace treaty to be signed so they could come home. Many were suffering from dysentery, malaria, typhoid and yellow fever and getting sicker and sicker. It took two weeks. From up in the mountains, Roosevelt wrote a letter to President McKinley that read, “The Army must be moved at once or perish. As the army can safely be moved now, the person responsible for preventing such a move will be responsible for the unnecessary loss of many thousands of lives.”

In early August, it was decided by President McKinley that the American soldiers could not go back to the towns and villages around the country to the celebrations and parades being prepared until they recovered from these tropical illnesses. If they did go home too soon, the country could suffer an epidemic. This was long before modern medicine.

And so President McKinley made a speech to announce that in returning to America, the 30,000-man army would indeed be transported back to America but would not be mustered out of the army until they completed one full month of military maneuvers at a remote and virtually uninhabited place called Montauk. Montauk had a deep-water port and train service. The soldiers should stay on alert and be ready should further trouble spring up.

McKinley did not mention that over half of them had come down with tropical diseases and he had chosen Montauk because it was in a northern latitude. And he did not mention that the stay might be longer if anyone had failed to either die or completely recover. They’d just have to see.

Montauk at this time was a treeless, windswept landscape of rolling hills and low shrubs. The air was pure and refreshing and you could see the horizon in almost every direction. It exuded health and well being.

A pier, called the Iron Pier, was quickly built out into Fort Pond Bay by the army engineers. And the members of our armed forces arrived aboard troop ships, not to parades and keys to the city, but to an army of nurses, doctors, aides and newspaper reporters. Many of the men had to be carried down from the ships on stretchers. Also arriving were tents, guns, wagons and ammunition. The horses had to be taken off by cranes with slings slid under their bellies.

Teddy Roosevelt leaned on the railing in one of the first ships to arrive and spoke to the reporters below.

“I’m in a disgracefully healthy condition! I feel ashamed of myself when I look at the poor fellows I brought with me.” He paused. “I’ve had a bully time and a bully fight! I feel as strong as a bull moose. I wish you all could have been with us.”

On the pier, Roosevelt talked further with reporters and waited as the rest of his men came down the gangplank, many assisted by others, then went with them on horseback or in ambulances to their assigned campsite in Montauk, a patch of about 10 acres of land at what we call Ditch Plains today.

It should be mentioned that Teddy Roosevelt might have been the most famous warrior in the army but he was not its leader. The leader was General William Shafter, who made his headquarters not in a tent but in the house that later became the Deep Hollow Ranch.

The encampment over the rolling, uninhabited hills of Montauk was vast, taking up nearly 28 square miles in all. It consisted of nearly 15,000 small white tents covering from where the center of town is today to the Montauk Lighthouse. There were larger tents for mess, for meetings, for kitchens and support and also hospitals, a detention hospital of 250 beds, a general hospital of 500 beds. Also called in were nurses and volunteers from the American Red Cross.

Teddy Roosevelt kept a diary of his one-month stay at Montauk. Many of the men had carried home small wild animals or birds they had trapped in the Cuban mountains. They were showcased in wooden cages with the men who had caught them, even taken along when the men lined up in great formation to take racing rides on horseback up and down the hills with their rifles near at hand. Photographer Frank Friedel took pictures of what life was like in Montauk at that time. There is the army, and that’s about it.

Photos include scenes of Roosevelt and McKinley talking in folding chairs facing each other in front of Roosevelt’s tent. Kerosene lanterns hanging from poles appear at the back. McKinley was there not only to give out awards to his soldiers and to talk to General Shafter, but also to talk to Roosevelt about his future. Before riding off with the Rough Riders, Roosevelt had served in government, briefly as Commissioner of the Police Department of the City of New York, as an Assemblyman from Manhattan’s silk stocking district and as the Assistant Secretary of the Navy. His future, McKinley believed, might be as the next governor of New York, and, maybe, as McKinley’s vice presidential candidate when he ran for re-election in 1900. Roosevelt said he would consider whatever he was asked.

Roosevelt wrote it all up in his diary. He spent one night at the Deep Hollow Ranch headquarters, invited there by Shafter. He noted that this was the first time in 10 weeks he’d slept anywhere but on the ground. Two weeks later, his wife and daughter came to visit him in Montauk and got put up at the ranch headquarters. In the end, 357 soldiers died of the tropical diseases at Montauk.

On September 3, President McKinley spoke to about 5,000 soldiers in Montauk on a great field. He said “I bring you the gratitude of the new nation, to whose history you have added by your valor a new and glorious page.” Soon thereafter Roosevelt spoke to his men and said, “you cannot imagine how proud I am of your friendship and regard.” His men presented him with a statue by Frederic Remington called “Bronco Buster” on that field.

A few days later, the First Infantry Division of the U.S. Army left Montauk aboard a Long Island Rail Road train to disperse to their home towns around the country. Teddy and his Rough Riders, a group officially known as Troop K, soon followed, as did the rest of the army.

Roosevelt became Governor of New York, then Vice President with McKinley and then, after McKinley died from an assassin’s bullet, the President in his own right. He is known for setting aside much of the western part of America to make it parkland, for implementing federal income taxes for the first time and for vigorously promoting America to become one of the great nations of the world. After his retirement, he became famous as a hunter and went off on numerous safaris to Africa in search of big game.

Teddy Roosevelt is memorialized with a museum at his family’s home in Oyster Bay, Long Island. Roosevelt should be further recognized at Montauk. Indeed, local historian Jeff Heatley has proposed that places throughout the entire town honor him with statues and plaques and so forth. As for me, I think it should be all in one place. At the present time, there is a remote, little-used hundred-acre park on the shores of Fort Pond, just to the west of where the Iron Pier and the troopships came in. That park, which has its own pier, should be re-named Teddy Roosevelt Park. On it should be re-created the landing site as it was in 1898, with the post office, the laundry, the mess hall, the press facilities, the warehouses, tents and the stores and other buildings that were present at the time of the landing.

It should be an attraction for the park, and a reproduction of the “Bronco Buster” statue could be displayed there. There could also be photographs showing Roosevelt and his men at Montauk in a building, along with photographs and artifacts of his later extraordinary career that in the end resulted in his visage being carved into the stone on Mt. Rushmore in South Dakota, alongside Washington, Lincoln and Jefferson.

WHY MCKINLEY CHOSE MONTAUK

About five years before the Spanish-American War, the President of the Pennsylvania Railroad, Austin Corbin, purchased the Long Island Rail Road in the hopes of building a freight terminal on Fort Pond Bay in Montauk for merchandise shipped across the Atlantic to the East Coast. He built the vast Pennsylvania Station in Manhattan, and he extended the tracks, which already had gone out to Southampton, all the way out to Fort Pond Bay at Montauk, even though almost nobody was there.

The effort to create a port on the bay foundered however, and Corbin died, thrown from a carriage when a team of runaway horses bolted. The great number of tracks, including a curving track that went out onto the Iron Pier, remain today.