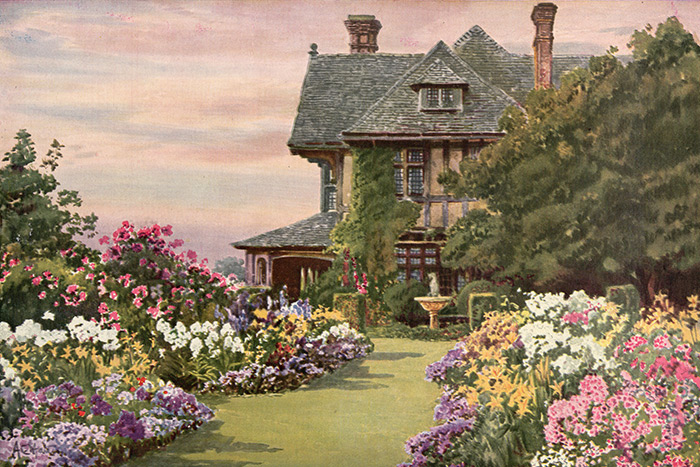

Hamptons Gardens of the Gilded Age

Above is a view of the luxuriant garden of the Wyckoff estate in Southampton. Gardens in the Gilded Age of the Hamptons were even more elaborate than they are today. In the Gilded Age, gardening was often one of the activities for the lady of the house. Well, most didn’t get down in the dirt and plant—mainly they directed their garden staff. But keeping all the gardens looking lush, weed free, and dead-headed was a full time job and numerous estates employed as many staff members for the outside maintenance as those working inside the house.

There are a number of amusing stories when one reads about the great gardens of the Gilded Age, and while working on the book Houses of the Hamptons 1880-1930, co-author Anne Surchin and I discovered many of these anecdotes, some from the Hamptons and others from the era.

One story I recall was when a lady of the house would walk her weekend guests through her garden to show off the glorious blooms. The gardeners who never seemed to stop, even on weekends, were instructed not to be seen and had a system to notify each other of approaching garden ladies. When one saw the Missus strolling down her garden path with guests, he would run ahead and tell the others. As they approached, the gardeners would hide behind hedges and other tall plants to maintain the illusion of effortless beauty. Once they passed, work continued.

At the Kiser estate, Westerly, in Southampton, landscape architect Annette Hoyt Flanders designed the magnificent landscape and gardens there. According to the Golden Age of American Gardens by Mac Griswold and Eleanor Weller, Flanders would personally direct the planting of full-grown trees, intent on angling them precisely to incorporate their silhouettes in her designs. In this time before labor-saving devices such as tree spades, her perfectionism meant quite a bit of work for the men in the hole, digging to accommodate and orient the tree.

Charles Smith, the foreman of the Frankenbach nurseries in Southampton, disclosed a technique he developed to deal with Mrs. Flanders when interviewed by Griswold: “Sometimes when we’d moved the tree about half way around in the hole and it looked fine to me,” he says, “I’d tell the men that the next time she asked for a little more this way or that, they should just shake that tree hard and groan a little bit. Always seemed to suit her just fine…”

Westerly is now owned by designer Tory Burch.

At the Southampton estate of James Breese, The Orchard, whose landscape was designed by the Olmsted Brothers, there was a famous marble fountain, the Frog Boy, in the center of the rose garden. Frances Miller, the daughter of James Breese, recounted in her autobiography, “Tanty”: Encounters with the Past, that her father thought the marble appeared too new when it was installed and looked forward to the patina of age. The statue did acquire the patina, only to lose it to the children of weekend guests who thought they were doing a favor for Breese by scrubbing away the ravages of time.

The Orchard is now the Whitefield Condominiums

At the Shinnecock Hills estate of Charles and Pauline Sabin, called Bayberry Land, they had renowned landscape architect Marian Coffin design a series of terraced gardens overlooking the Great Peconic Bay, which necessitated the purchase of an entire farm to provide topsoil for the regrading and enrichment of the sloped sand property.

Bayberry Land was demolished in 2004 in order to construct the Sebonack Golf Club.

Another famous garden designer, Rose Standish Nichols, who designed the early gardens at Ballyshear in Southampton, once said, “Many Gardens have ‘arrived’ because a man’s brawn has been directed by a women’s brain.”

Ballyshear is now owned by former New York City mayor, Michael Bloomberg.

Of course, no story about Hamptons gardens would be complete without the infamous East Hampton home of the Beale family. Grey Gardens, which is still a private residence in East Hampton, didn’t get its name until the second owners of the property, Robert Carmer Hill and his wife Anna Gilman Hill, created the famed gray-toned gardens shortly after they bought the estate in 1913. Anna describes the unique palette in her book, Forty Years of Gardening: “It was truly a gray garden. The soft gray of the dunes, cement walls, and the sea mists gave us our color scheme as well as our name. We used as edgings all the low gray foliaged plants such as nepeta, stachys, and pinks. Clipped bushes of santolina, lavender, and rosemary made gray mounds here and there. Only flowers in pale colors were allowed inside the walls, yet the effect was far from insipid.” Anna’s time spent at Gray Gardens clearly made an impression on her, asserting “Gardening in Suffolk County spoils you for gardening in North America.”

Then again, to have a beautiful garden, there are three simple ingredients which could not be better described than by the title of Nancy Fleming’s book about Landscape architect Marian Coffin: Money, Manure & Maintenance.

This successful formula is just as true today as it was back then. Once, while I was attending a local garden tour, I overheard a woman admiring the delphiniums and telling the others who were with her that they must come and see her delphiniums later, since they were spectacular this year. One of her “friends” commented that her own flowers were not so good this year, but she could also have a spectacular garden if she had as many gardeners as her boastful friend!

Gary Lawrance is co-author of Houses of the Hamptons 1880-1930 with Anne Surchin. He maintains a popular Mansions of the Gilded Age Facebook Group and Instagram gallery.