Stuart’s Ashes: Saying Farewell to Stuart Vorpahl

Bonacker Stuart Vorpahl’s ashes were dropped from a fishing boat out of Montauk at his favorite fishing grounds last Saturday evening, a mile off the entrance to Three Mile Harbor. He had died earlier this year at 76. Vigorous until the end, he had known the end was coming. He asked for his ashes to be sent off in a Viking ship, on fire, at his favorite fishing grounds. And his wife, family, local officials and friends—about 100 people in all—gave him what he wanted.

Not enough can be said about Stuart Vorpahl. He was an upstanding, honorable and beloved fighter for fishing rights in this community. One might compare him to an earlier Bonacker—Samuel “Fish Hook” Mulford—who went to London in 1704 to fight to have the tax on whale oil rescinded by his king. Mulford had fishhooks sewn into his pants pockets when he left East Hampton. He’d heard there were pickpockets in London. He spoke before Parliament, it got him nowhere, he came home.

Bonackers today—as a clan they live largely in Springs and Amagansett—speak with the same accent that the Bonackers spoke with back then. It’s soft, quick, almost a different language than regular English.

Stuart Vorpahl was one of them. He dropped nets and gathered up bags of fish. He tended lobster pots. He minded his boat. The rights of the locals to fish and work the local bays and waters goes back to the Dongan Patent of 1686, a king’s declaration still in force today. Vorpahl kept a copy of it on his boat in a plastic sleeve. When stopped by a state officer requesting his fishing license, he’d present the Patent and, when ticketed, refuse to pay fines to the State of New York to satisfy the tickets. He’d go to court. The Dongan Patent always won. Two years ago, after another victory and a promise to pay him $1,000 for the lobster and fish that had been illegally seized by DEC workers, he told people that when he got the money, he’d use it to take his wife Mary on a “trip to Paris.”

A year later, the money still hadn’t come. Stuck in paperwork, he was told. Instead, our local Assemblyman arranged for the $1,000 to be given to him from a special fund the State has for occasions such as this. It was fitting.

There was a covered-dish luncheon for about 50 people out on the front lawn of the modest Vorpahl home on Three Mile Harbor Road on Saturday. Living just up the street from him, I’d befriended Stuart and come to love him. Afterwards, at 6:30 p.m., the 50 of us, together with about 50 more, left Montauk aboard the Viking Starlight to comply with Stuart’s wishes. We all talked about our times with Stuart on our way out. I met people from as far away as California who had come for this.

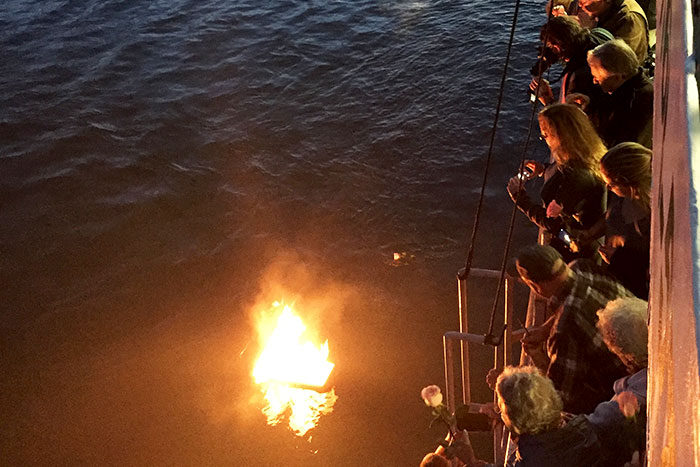

Seas were calm, and we arrived at the fishing grounds at sunset. Everyone had been given a rose. A small wooden replica of a Viking ship about three feet long appeared, with Vorpahl’s ashes inside. It was carried to a metal ladder that went over the side. A minister offered up Vorpahl to the heavens. We all sang “Amazing Grace.” Then a sailor carried this small replica of a Viking ship, launched the ship, set it on fire and caused it to drift off. From the deck above, we threw out after it a blizzard of white roses, which floated alongside for a while.

We watched it for nearly half an hour. Finally, in that darkness, the boat’s fire flickered out and it sank. Heading back to Montauk meant heading east, and doing so meant we were all able to watch the enormous Harvest Moon rise up over the sea. What a fitting end, we all told one another. Once back in the harbor, there were fireworks across the way. No one on board knew why.

This was a day and evening none of us will ever forget. Goodbye, Stuart.