Wreck of the Sylph: English Warship Comes Ashore in Southampton

One of the worst shipwrecks ever to take place on the eastern end of Long Island was that of the British warship HMS Sylph. Its keel hit a sandbar a few hundred feet offshore in the middle of a bitter cold and windy January night, just a few miles east of downtown Southampton. The collision with the sandbar at 2 a.m. on January 16, 1815 knocked the topside crew off their feet and tangled the lines as the ship cut through it into the shallows nearer to shore. And there it stuck, with the crew crying for help in a wild and heavy surf, unable to recover.

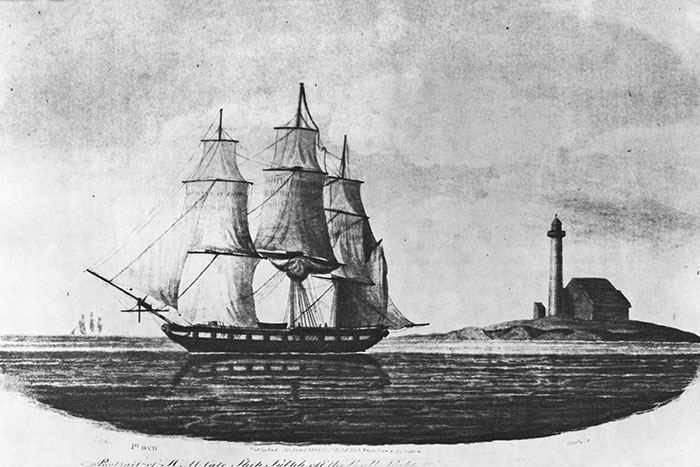

Somehow, on that dark night, their voices were heard on shore and men soon came to the beach on horseback to see if they could help. But as they assembled, this wild and windy night turned even worse, and though a few were able to stay, many turned back and went home, vowing to return in the morning if they could. Those aboard this warship, 117 people in all, had no place to hide. Although not a man-o-war, this ship was the next step down—a three-masted, 22-gun, 100-foot long war “sloop” as it was called at that time, a ship of the line that would accompany the British fleet of men-o’-war on their missions, taking on the small prey in the American Navy on their own.

The Sylph was quite familiar to the Southampton residents. It had come to join the blockade and bombardment of eastern Long Island during the War of 1812, and, for a year prior to this January night, had patrolled Long Island Sound and the ocean, participating in the English blockade by sinking merchant ships and dealing with occasional challenges from the few American frigates that constituted the American Navy at that time, usually with disastrous results for the Americans.

RELATED: Not a Fun Job–Meet the Wreckmaster, the Man in Charge of the Cargo

During this war, the British, to reinforce the blockade, even raided the towns to burn their ships while they were in their slips. HMS Sylph arrived to join the blockade of Long Island Sound in May of 1814. Together with a similar sized ship called the HMS Maidstone that first week, they engaged nearly a dozen small American gunboats protecting a convoy of merchant packet boats headed for Europe. The packet boats got through. But then a big British man-o’-war with 74 guns arrived and the Americans retreated to Guilford, Connecticut.

The Sylph participated in a battle at Horton Point on the North Fork in late May where the British engaged the Sag Harbor militia trying to re-float a primitive early version of a submarine that had accidentally beached there. The British won and destroyed the sub. In June, the Sylph fired broadsides at the bluffs at Northville where American militiamen were trying to come inland and attack a British outpost. The militia was driven off.

And then, in January 2015, the Sylph shipwrecked at Shinnecock. It crossed the bar at 2 a.m. and could not get back out. By dawn it was seen that about 60 men had strapped themselves to the masts to stay clear of the freezing sea, but then at 8:45 a.m., with the weather worsening and creating huge waves, the Sylph’s masts cracked off, sending bodies flying, rolled over keel upwards and then broke in two. In spite of this, somehow the Americans on shore were able to finally send a small dory out through the surf to try to save Purser William Parsons and three seamen who were seen clinging to the ship’s spars. They succeeded, but a fourth sailor slipped and fell into the sea while trying to board the dory and was soon gone.

On shore people wept and turned away as the frozen bodies drifted in from the sea. Some were the bodies of young children, apprentice seamen. It finally ended when the storm wore itself out later that afternoon, leaving the remains of the Sylph a helpless pile of wreckage on the beach. All in all, 114 of the 117 British sailors onboard perished.

Fifty years after this disastrous shipwreck a man named Richard Markham wrote a poem about it for his book Around the Yule Log.

Did we know the craft? Aye, we knew her well

From Montauk Point to Fire Island light

Many a time from her decks had a shell

Screamed through the air in the quiet night,

Waking the silent village street

With its roar and tramp of flying feet!

Many a night had a ruddy glare

Lighted the landscape far and near,

As some old homestead and barns were burned,

And the labor of years unto ashes turned.

[The shipwreck is then described. The poem continues:]

We buried the dead that came ashore;

You may see their graves at the inlet still.

But the wreck turned out a prize indeed,

And we picked her bones with a right good will

From her guns and timbers of cedar-wood

We built us a meeting-house strong and good

And I’ve often heard the parson tell

That he heard these words in her swinging bell:

“To pruning hook ye shall beat the sword;

For the wrath of men shall praise the Lord.”

A plaque inside the St. Andrews Dune Church in Southampton is affixed to a piece of red cedar plucked from the wreckage of HMS Sylph.

For a long time after the wreck, a working cannon from this ship, a 24-pounder, sat on the village green in Bridgehampton. It was fired on the Fourth of July. And people who were there at the time said it was a wonder that no one ever got hurt from the firing of this cannon. It was one wicked weapon.

There were also occasions when this cannon would be hauled to someone’s home to be fired to celebrate a wedding reception after the ceremony at a nearby church.

There was speculation that somehow the Sylph was steered deliberately across that bar by a crewman mad at the captain, George Dickens, for one reason or another. At the time this ship crossed the bar, the wind was blowing from the north, which would have sent a big sailing ship like this away from the shore. It just doesn’t make sense otherwise.

The wreck of this ship took place just a month before the Treaty of Ghent ending the war was ratified by the U.S. Congress on February 1815. The war had taken place at a time when the United States was still trying to decide whether it should be a confederation of individual states loosely allied with one another or a strong federal union as one of the world’s great powers.

The cause of this war, so close after the Revolutionary War, was the need England had to stop France’s emperor Napoleon from conquering Europe.

England built many new warships to fight Napoleon, but it did not have enough trained seamen to man them. As a result, England embarked on a program of kidnapping foreign sailors on the high seas. It was called “impressment.” Many sailors came off American merchant ships, and this angered President James Madison.

From the British perspective, however, it made perfect sense. They were looking for sailors born in England who had immigrated to America. They said: Born in England—then you’re still English. They’d look over the crew’s papers. In a very real way, they were challenging America’s authority. America took up the challenge.

President Madison finally declared war. Within a week, he had sent a hastily organized American army into Canada to try to pry Canada away from its British masters. The Americans were beaten and retreated to Detroit, and when the British threatened them there, General William Hull surrendered Detroit without firing a shot. He was subsequently relieved of his command, as well he should have been.

The British attacked Washington and set fire to both the Capitol and the White House, sending President Madison and his wife fleeing from the breakfast table. The British then moved on to Baltimore to try to take that port city.

Francis Scott Key, an American poet, was on a ship anchored offshore of Baltimore. If the British could take Fort McHenry, they could simply walk into Baltimore and set the whole town on fire. From its ramparts, Fort McHenry flew one of the largest American flags ever made. It measured 32 feet by 48 feet and took two weeks to make. The British fleet bombarded the fort for 26 hours while Francis Scott Key watched from afar. You know what flag was flying when it was all over. The British withdrew.

Another battle lost by the British took place earlier in the war in July 1813, when a large force of British warships arrived off Sag Harbor carrying Redcoats intending to capture that town. Sag Harbor was a big, thriving whaling town and a port of entry to the U.S. Late on the night of July 13, a force of British Redcoats were rowed to Long Wharf to start the invasion and were almost immediately driven off by Americans firing a big cannon from atop Turkey Hill. It had been set up to target the end of the Wharf where they correctly assumed the invasion would begin. The British climbed back into their small boats and rowed to their ships offshore. Soon the fleet departed.

Napoleon lost his war in 1814 and was sent off to exile. (He returned from exile later to try again and got beaten at the Battle of Waterloo in November of 1815, this time to be sent to Elba.)

With the war with France over and the British fleet back home, there was now no further need for the British to impress any American sailors. As a result—and since anyone could see the war with America was a stalemate—the British decided to sue for peace. The negotiations went on for a while. America surely wanted peace.

In November of 1814, the general terms of the treaty to end the war were agreed upon. The Parliament voted to approve it four days later and signed it. But the American Congress wanted to talk about it for a while. In January of 1815, they were still talking about it when an English general in the Gulf of Mexico led his Redcoats ashore to seize control of New Orleans. An American army led by Andrew Jackson counterattacked. The British were sent reeling.

And then the Sylph shipwrecked at Southampton later that month. And maybe this was the final blow. Congress signed the peace treaty with England in February of 1815. And we’ve been friends with the English since.

* * *

We know the details about the shipwreck of the Sylph because a Southampton resident, H.T. Dering, wrote a letter to his sister the day after the shipwreck, describing the horrors he saw when he went down there by horseback at dawn. He ends his letter this way:

“What do you think sister? If we should not have peace by next year and I should live I think it will be best for me to go to West Point…Write me what you think of it. If I do not go there how shall I get my living in this world? I begin to grow tired of South[ampton] and wish to be doing something but when I consider my inability to do any kind of business I redouble my diligence at my studies. My…respects to Aunt Corwithe and S.

Believe me your affect[ionate] Brother”

H.T. Dering