All Aboard: Changing a Young Man’s Life, One Note at a Time

Yesterday I received an email from a young man named Mark Petering, who lives in Kenosha, Wisconsin. One weekend 13 years ago when he was a college student, he stayed at our house in East Hampton as a houseguest at the request of Eleanor Leonard, who was the President of the Music Festival of the Hamptons. His music would be played there.

I hadn’t heard from him since then. Here is what he wrote.

“Hey Dan. You changed my life. Hope you are well. I am happily busy being a dad (photo attached of Henry.)”

I replied and asked him if he wanted me to send him a copy of a memoir I wrote in which he is mentioned. The chapter is about my connection with Eleanor Leonard and the Music Festival she ran for 15 years. “I already have two,” he replied. “That book is how I got tenure.”

He also attached a link to the seven-minute piece of classical music he wrote that was performed at the festival that year. If, after reading this, you wish to hear it and see it—it is a remarkable video—you can watch it below.

“Incidentally, we also made it into the Gramophone—Top Ten All Time (article attached),” he also wrote.

Gramophone is one of the leading magazines published for the classical music industry. The article lists Petering’s “Train and Tower for Chamber Orchestra and Tape” as the number eight best classical piece about railways. Number nine is a piece by Berlioz.

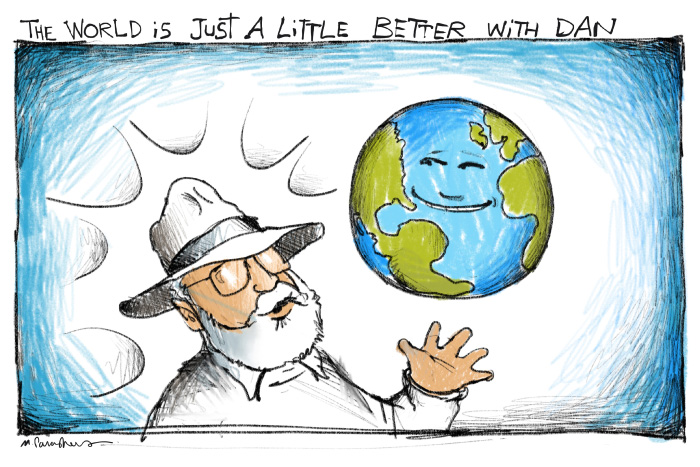

I think the time has come to put all these pieces together to tell this remarkable story. I have often been correctly accused of making stories up for Dan’s Papers. Here is one that is right up there with the most fantastic of these stories. And yet it is true. And yes, it did change this man’s life.

From about 1995 to 2009, a wealthy woman named Eleanor Leonard, who lived oceanfront in Bridgehampton, promoted an annual one-week-long Music Festival of the Hamptons in honor of her granduncle, the famous pianist Benno Moiseiwitsch. Mozart was played, Stravinsky was played, Beethoven and Bach were performed. At each festival, one afternoon was set aside as children’s day and Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf—narrated by a celebrity (playwright Adolph Green one year, raconteur George Plimpton another)—was played while members of the Bridgehampton Ballet Society performed in costume. Because I love music, I joined Eleanor’s Board of Directors, which generally consisted of meeting a few times a year at her home to listen to her tell us what famous musicians would be featured in the upcoming year.

The locale for the festival was a huge white tent located on the grounds of Sayre Park in Bridgehampton, parallel and adjacent to the Long Island Rail Road tracks. Light fare and wine were served at the back of the tent each night. Attendance was modest. Certainly, listening to classical music was not high up on things to do in the Hamptons. It was, however, culturally wonderful for all those who did attend.

In 2002 I was in the audience. During a performance of Beethoven’s “Prometheus” Overture, exactly at 8:06 p.m., the westbound Long Island Rail Road train came roaring along through the dark just outside. The thin tent presented no appreciable sound barrier. The celebrated German composer Lukas Foss, who was conducting that night, simply continued to swish his baton this way and that as the train clattered through. It was as if it never happened.

But I thought about this intrusion. It happened every year at this time of the evening. And it gave me an idea. What if we could incorporate the train into the music being played? Wouldn’t that be something?

That fall, at a board meeting, I proposed exactly that to Eleanor. She, and all the other board members, loved the idea. And so we put it into action. But where, in the pantheon of classical music, was there a piece incorporating a train? No one knew of any. And so we decided that an original piece be created. It would be a competition, nationwide, for music students. It should be between 5 and 15 minutes long and include a train. The winner would receive $500 and the honor of having the piece performed at our festival the following summer.

We sent out fliers to music conservatories around the country. Tack these to your bulletin boards. We did a media blast. And one day I went up to Sayre Park and recorded the train sounding its whistle as it roared by. We sent that out. The winner would be selected by conductor Lucas Foss himself.

The train, we knew, passed the festival at 8:06 p.m. That meant it arrived at the Bridgehampton Station around 7:55 p.m. But because trains are not exactly on time, we’d need a cell phone call from someone on the train as it was arriving to tell us when to begin. Because of that, I wrote to the President of the Long Island Rail Road for help.

We had 61 entries over the winter. And I suppose by now you have realized the winner was Mark Petering, then a music student at the University of Minnesota. At the request of Eleanor, we hosted him at our house the weekend of the event. He was a personable, thoughtful young man totally involved with the music he was studying, and we were happy to have him.

The tent was packed full to overflowing on the evening of this performance. It was the biggest crowd that ever attended the Music Festival of the Hamptons.

The railroad had declined to let their regular train be used for this. Instead, they sent a SECOND train, all for us.

That afternoon it arrived and by evening was idling on a siding at the Bridgehampton Station waiting for the signal to go. A New York Times reporter was there. Reporters from the BBC and NPR were there. The President of the LIRR was there. And, as a surprise, Mark’s parents had traveled separately to Bridgehampton for his big moment. They had with them the biggest bouquet of flowers I have ever seen and were ready to present it to him onstage at the end, win, lose or draw. And of course, our videographer was there to record the 7-minute performance and, especially, the 10 seconds of that train roaring through on cue. Or not. It would come, Mark told us, at the very end of the piece.

And so it began. The piece begins softly with violins in the lead plucked rhythmically as an invisible train leaves a station, and as it proceeds along, it builds, first with the oboes and cellos and then with the French horns until after the fifth minute, a sense of mystery arrives in a minor key as a snare drum tries to take over. The pace speeds up, now a kettle drum rumbles in, trumpets and horns shriek and then, in a great crescendo—the audience sees that train come barreling through on the track just alongside the tent—the tent flaps had been rolled up ahead of time—filling it with its horns blaring and its lights flashing.

A great cymbal crash signals the concerto’s end, and the train moans on and on, softer and softer, disappearing toward Southampton.

With that, everyone in the audience, as one, leapt to their feet, screaming and shouting. All the musicians onstage jumped up and down, waving their instruments. It was a home run. It was pandemonium.

This was a moment, on that soft summer evening in July, that none of us will ever forget. Just go to the link.

And so, Mark Petering graduates, becomes an associate professor of music at Carthage College, gets married and starts a family. And, as with any good fairy tale, lives happily ever after. And it’s true. I’m so happy for him.