Did Major John André Whip William Russell in Sagaponack?

One of the biggest mistakes I made during the 55 years I edited this newspaper was unintentionally running a front page story demanding that the authorities do something they had already done. I then compounded the error a week later by writing a story in which I insisted people who wrote me saying it had been done were wrong.

The whole thing had come about because a man driving a Toyota Camry late one Saturday night in 2005 had run into the Bridgehampton Founders Monument on Main Street, knocking it askew. The driver was not hurt. The car suffered some damage. The Founders Monument, which is the 12-foot-high marble monument with the eagle on the top in the center of town, was knocked off center by six inches.

I wrote about this. Money was soon appropriated from the State of New York. And there would be enough to not only slide the monument back to its proper position, but also to shine up the brass plaques that adorn it. With leftover money, they’d also shine up several cast iron historic markers in Bridgehampton and Water Mill. These were on six-foot poles in these towns. One was across from the Founders Monument, and noted that on this site stood a famous revolutionary war inn called Wick’s Tavern. Another was down by Sagaponack’s two-room schoolhouse between there and the Sagg General Store, and it read “On this Site Stood the Spider-Legged Mill Where During the Revolutionary War, Major John André, the British Spy, was Tied to a Post and Whipped.”

Months earlier, I had written a story about this whipping. I noted that this sign was beside the sidewalk where the kids from the school, grades K through 8, walked to get ice cream cones at the Sagg Store. It was a rather nasty sign. Was this bit of history something we would want our children to read as they walked down that sidewalk? Also, the sidewalk between the school and the store was the only sidewalk in the entire village. Who had put it there, anyway?

This article resulted in a reader calling to my attention the fact that the sign was wrong. It had not been Major John André who got whipped. It was a patriot, William Russell, who got whipped. André, the Englishman, was the whipper.

The reader told me the correct sign had been stolen 10 years earlier. Five years later, the state made a new one made. But they got the whipper and whippee backwards, it seemed.

I looked into it. Calling the state’s Department of Education office, I determined that indeed the old sign had been stolen. However, after it was stolen, no records in Albany, where it had been ordered, or at Catskill Castings in Bloomville, NY. where it had been made, could be found of exactly what it said. As a result, state officials came to Bridgehampton and asked around. This is what old timers told them. A patriot had whipped the evil Major André.

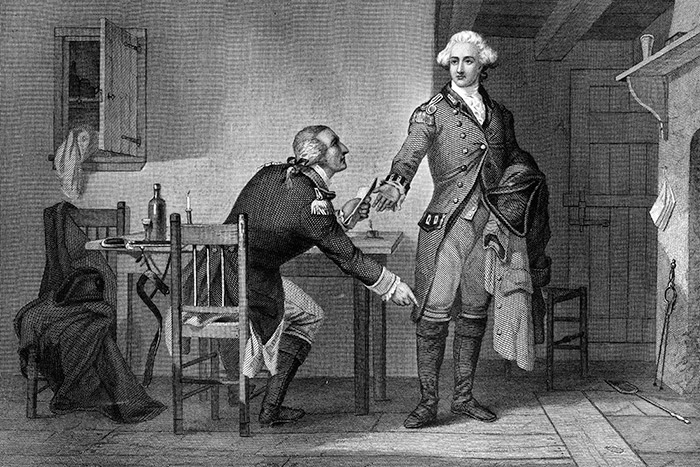

Major John André was hanged during the Revolution. I knew that from my history studies. He had been a spy for the British and had famously received the plans from Benedict Arnold that would have allowed the British to attack and defeat the Americans at West Point. He was caught and hanged in 1780. But all that took place upstate. Had he been in the Hamptons? I guess so. The British, after defeating George Washington at the Battle of Long Island in August of 1776, had then required all residents of the island to sign a paper pledging loyalty to the King. Maybe André was out here whipping people who wouldn’t sign.

I relayed what I knew to the state, and they called back to say that indeed, they’d found André was the whipper, not the whippee. And they would make a new sign.

Two months went by. The monument was fixed up. The historic markers got shined up. And then I made this totally disastrous mistake. We were still waiting for the new sign. Among those shined up was the bad sign. What a waste of money, shining up a wrong sign! What was wrong with these people?

Accompanying this story’s front page was a picture I took of the old sign, all shined up.

The old sign, as you recall, read, “On this Site Stood the Spider-Legged Mill Where During the Revolutionary War, Major John André, the British Spy, was Tied to a Post an Whipped.”

But when I went down to take its picture, I hadn’t carefully read the shined up sign.

Two days later, I received letters from four people saying that the all shined up sign had it correct. Having failed to notice that this indeed was the fixed sign, I now wrote these four people back saying look again, this is still wrong. And if it’s a new sign they put in there, they are repeating the error and this is even worse!

And I put THAT in the paper.

I received no reply from any of these four people after that, but one day, I happened to pass the sign driving home from work, and guess what. This was indeed the sign with the correct wording the state had promised. And it wasn’t shined up. It was new. After that, I received no further reply from anybody. I was an idiot. Yes, indeed.

All of this is relevant today because, as Newsday reported, there is new information about Major John André. Letters written by him were found by Claire Bellerjeau, the resident historian in Oyster Bay’s Raynham Hall Museum, as she went from Toronto to the University of Michigan and elsewhere, that shed new light on Major John André. Until now, there had been no evidence whatsoever that Major André ever set foot on eastern Long Island. There was a hint that he did. He was, indeed, the aide de camp to General Clinton, who had defeated George Washington in the Battle of Long Island, and in 1777 Clinton had come out east.

Now, in these letters, written in 1779, Major André writes to General Clinton that he was at the Townsend home in Oyster Bay and refers to seeing Colonel John Graves Simcoe at a house out east, which some say was in East Hampton. André also drew a map, I’d read, which was found among these letters, noting a spot where there was an inn near the Shinnecock Canal.

André is described in many accounts as a happy-go-lucky young man of 29, honored and proud to be fighting the war for his country. This information totally jibes with what has been written about him by others prior to his hanging, which took place in Tappan, NY in 1780. He told jokes, loved his friends, often played tricks on people and was a generally all around good guy.

Here’s what he did wrong. In 1780, he came up the Hudson aboard the British sloop Vulture and anchored offshore of the fort at West Point. The British occupied the east side of the Hudson. The Americans occupied the west, with the fort on it. Two American oarsmen rowed out to the Vulture and rowed back to the American side with André. There in a field on the shore he met with Benedict Arnold, the commander of the fort at West Point, who had arrived sitting on one horse and holding the reins to another for André. They rode off into the woods. There, Arnold showed plans of the fort to André, and pointed out the weaknesses of the fort, which, if exploited, could result in the fort’s surrender. In exchange, Arnold was to receive 20,000 pounds (approximately $3.5 million).

While they talked, however, American artillery fired on the Vulture, causing it to flee back down to New York City without André. André went into hiding, and later was arrested in Tarrytown, NY on the American side with six pages of these plans in his stocking.

About to be hanged, he maintained both his deportment and his spirits right up to the hangman’s noose. The day before, he had made a sketch of himself so others could remember him. He forgave everybody who’d convicted him. He had earlier asked American officer Benjamin Tallmadge, the Head of Continental Congress Intelligence, if what would happen to him was what happened to the American spy Nathan Hale and was told yes. Nathan Hale was the American spy who, when arrested by the British, said he regretted he only had one life to lose for his country.

“During his confinement and trial,” wrote the American physician James Thatcher, who witnessed it all, “he exhibited those proud and elevated sensibilities which designate greatness and dignity of mind. Not a murmur or a sigh ever escaped him, and the civilities and attentions bestowed on him were politely acknowledged.”

Dr. Thatcher wrote the following in Military Journal of the American Revolution, published in 1834:

“Having left a mother and two sisters in England, he was heard to mention them in terms of the tenderest affection, and in his letter to Sir Henry Clinton, he recommended them to his particular attention. The principal guard officer, who was constantly in the room with the prisoner, relates that when the hour of execution was announced to him in the morning, he received it without emotion, and while all present were affected with silent gloom, he retained a firm countenance, with calmness and composure of mind. Observing his servant enter the room in tears, he exclaimed, ‘leave me till you can show yourself more manly!’ His breakfast, being sent to him from the table of General Washington, which had been done every day of his confinement, he partook of it as usual, and having shaved and dressed himself, he placed his hat upon the table, and cheerfully said to the guard officers, “I am ready at any moment, gentlemen, to wait on you.”

Then they hanged him.

This didn’t sound like anybody who might have tied William Russell to the Spider–Legged Mill in Bridgehampton to whip him.

And now there was this: This past September, Dan’s Papers joined the Bridgehampton Museum as the main presenter of the Bridgehampton Road Rally & Tour d’Hamptons. At this event, a parade of some 40 historic motorcars were driven through the streets of the town to celebrate Bridgehampton’s motor racing heritage. For many years, crowds came to town to watch racing cars not only drive through the back roads, but also around the Bridgehampton Race Circuit north of town at speeds approaching 200 miles an hour. Drivers such as Jackie Stewart, Sterling Moss and Bruce McLaren battled it out at races here.

Many photographs were taken both at the track and along these back roads, and at this year’s Road Rally; one old photograph was available to be seen at the museum that was of special interest. It was taken in 1951, and in it cars race past crowds along Sagaponack Road and Ocean Road and at one point pass a historic sign near the Sagaponack School that tells a bit of the story of the Revolutionary War.

It reads “Site of Spider Legged Mill at which Major Cochrane tied William Russel during the Revolution and ordered him whipped until bloodied.”