Jobs Jobs Jobs: Trump Orders Bulova Factory to Reopen in Sag Harbor

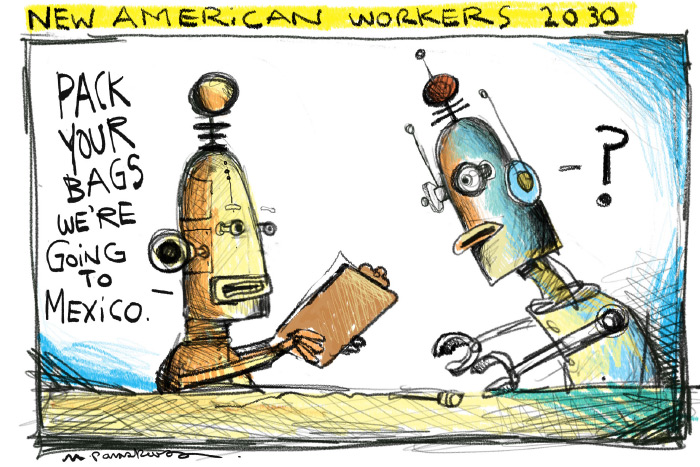

Last week, Donald Trump announced that after negotiating with the executives from Carrier Air Conditioner Company, in Indianapolis, the jobs of 1,000 workers have been saved. Carrier had been threatening to move the Indiana-based factory jobs to Mexico. But no more. Or at least half no more. There are 2,100 jobs at the Indiana factory. The agreement is that only half the jobs would go to Mexico. The other half, with government subsidies for Carrier, would remain right here in the good old U.S.A.

Rumors are, now Trump is turning his attention to Long Island, where company after company has moved to other countries, many to Mexico. He’s starting on the eastern end of Long Island, and after he fixes things here, he will move west, to Riverhead, Huntington, Medford and, eventually, to Long Island City, which has hundreds and hundreds of unused factories and warehouses just waiting for the return.

Out east here, Trump has located the most easterly of the factories that have closed and gone to Mexico. It is the former Bulova Watch Company factory in Sag Harbor, and it is Trump’s intention to get this factory working again with more new American factory jobs for the citizenry. The factory began its life in the last decade of the 19th century when heavy industry bustled throughout its four stories of factory rooms making watchcases for the thriving wristwatch industry in America. Factories elsewhere made the works. Somebody had to make the cases. And that was done here in Sag Harbor.

The chain-link factory gates opened at 7 a.m. every day except Sunday—a day of rest—and the hundreds of Sag Harbor workmen in hardhats carrying their lunch pails shuffled in to go to their work stations.

The man who founded what would become Bulova Watchcase, a Mr. Fahys, it was said, was a fair and honest man. “A penny saved is a penny earned,” was one of his slogans. He walked around the building handing out pennies once a week. He also said “a dollar a day for a dollar’s worth of work a day,” or maybe it was “a dollar a day keeps the doctor away.” But over the rattle of the machinery and the hissing of the steam from the boilers, it was hard to actually hear.

The noon whistle would sound twice a day. The first was at noon, when the furnaces were tamped down and the men would go sit out on the window ledges on every floor with their feet hanging down to eat their lunches. They’d talk about Babe Ruth or Al Jolson or Lillian Gish, and they’d take the full half-hour, even if they were done early. Then it was back to work.

The pieces of the watchcases continually came trundling down the conveyer belts, and the workmen in their rubber aprons had to assemble each watchcase as it marched by as fast as they could to get it ready to go to the quality control worker at the next station to make sure it was done right, then off to the cardboard box boxer and the label attacher and then to the forklifts and off to the waiting trucks.

At five, the whistle would sound again and the men, weary from a fair day’s work at the benches, would file out through the gates and go home to their wives and children in the little houses throughout the town, where their dinners, a good cigar and maybe a drink awaited.

Then it was off to the Black Buoy or the Sandbar, the two dives on Main Street in the center of town where they could drink and play cards and shoot pool until 9 p.m. Then it was home to bed. Tomorrow was another day. And they’d have to be up at 6 a.m.

Mr. Fahys might have retired with honors and maybe a gold watch, but he unfortunately continued into the Depression and had to close in 1931. In 1937 Bulova re-opened the factory. Bulova’s slogan was “America Runs on Bulova Time” and it was a so-so employer, people said, whereas Fahys was a wonderful employer, but it was still work. Rumors were—not true—that they speeded up the conveyer belts 10% and they required every workman buy a watch at retail to help the company along. On the other hand, they had Employee-of-the-Month awards and sometimes picnics, unless it rained. Although that may or may not have been true, either.

Eventually, in 1981, the owners of Bulova left Sag Harbor. Did they succumb to the rhythmic call of Mexico—or somewhere—and move away to where labor was cheaper? Mongolia, some people said. Anyway, they never returned.

And now, people tell me there are Bulova factories everywhere in Mexico. They say from border to border there are more Bulova factories in Mexico then there is tea in China. Meanwhile, the four-story Bulova factory languished in silence here in Sag Harbor for years and years and years. As it aged, unused, an occasional brick might fall onto the head of one of the tourists from New York who were walking on the back streets. This was bad. So scaffolding was put up all around.

The Trump team is aware, they say, that after 35 years abandoned, the factory building was bought, fixed up and turned into a luxury residential property where units cost several million dollars each. Many have been sold. A few remain.

Now these owners will be bought out, in Trump’s plan, and moved out. Many of these owners won’t even care about that happening, his people say, because they are well-off people with many homes around the world who are only occasionally here in Sag Harbor. These people are to be blessed by a huge tax cut for the rich coming just as soon as Mr. Trump takes office. A little slice of Sag Harbor lost will thus be just an amusing annoyance for them.

In their place will come 1,100 factory workers from Indiana whose jobs went to Mexico (while 1,000 were saved). They will have been re-schooled and re-trained to learn how to assemble watchcases instead of air conditioners, which Trump says will not be a big deal, and they will now take their places with their wives and kids living in the quaint little Sag Harbor houses in which the New York summer people now live. As with the condo dwellers, they will not mind. They’ll be thinking of the tax cut. And they will be able to share in the communal joy of having gone hand-in-hand with Trump to re-energize the Sag Harbor community in a way that will surely “Make America Great Again.” We will have done our part.

Tears will come to the eyes of the people of this community when they can see the fluttering of the American flag on the roof, the name BULOVA back on the brick walls, the flickering lights of the furnaces inside, the steam pouring out of the chimneys and the hundreds and thousands of watchcases that both pour into the backs of arriving trucks and swing on the wrists of every proud Sag Harbor citizen happy to be returning to the days of yore.

The conversion back to Bulova is expected to take about a year. After that, the men from Trump say, they expect to turn their efforts to the other former factory in that town, the cluster of buildings by Long Wharf at the other end of Main Street, that, not long ago, were used as warehouses but, before that, were the site of the U.S. Navy Torpedo Testing program for World War I.

War may be over. But it could come again. If it does, our torpedoes and our workmen and our Rosie the Riveters will be ready. God Bless America.