Tesla, Edison, Marconi: The Battle to Light the Night and Transmit Sound on the East End

In 1908, a physicist from Croatia who was building an enormous electric power plant here on Long Island’s East End wrote:

“As soon as completed, it will be possible for a business man in New York to dictate instructions, and have them instantly appear in type at his office in London or elsewhere. He will be able to call up, from his desk, and talk to any telephone subscriber on the globe, without any change whatever in the existing equipment. An inexpensive instrument, not bigger than a watch, will enable its bearer to hear anywhere, on sea or land, music or song, the speech of a political leader, the address of an eminent man of science, or the sermon of an eloquent clergyman, delivered in some other place, however distant. In the same manner any picture, character, drawing or print can be transferred from one to another place. Millions of such instruments can be operated from but one plant of this kind. More important than all of this, however, will be the transmission of power, without wires, which will be shown on a scale large enough to carry conviction.”

That date is not a typographical error. This was 109 years ago. The man who wrote this was predicting the invention of the smartphone.

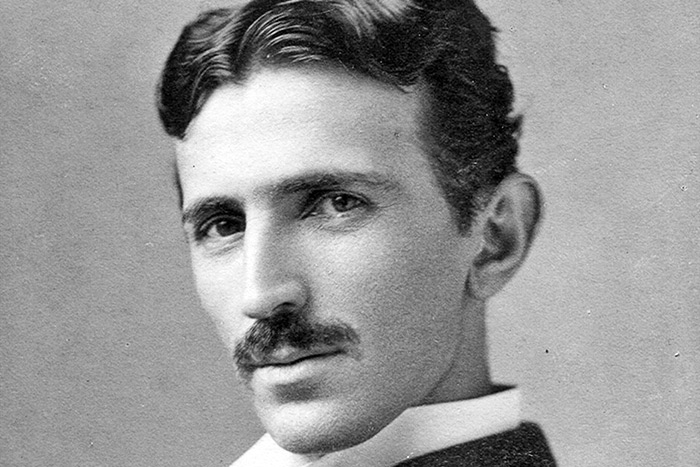

Nikola Tesla was 52 years old at that time. His projected power plant, soaring 190 feet into the sky and backed by J.P. Morgan with the equivalent in today’s dollars of $100 million, was going up in Shoreham, Long Island.

Today it lies in ruins, not far from the ruins of the $6 billion Shoreham Nuclear Power Plant that was abandoned before its completion in 1992—a remarkable coincidence.

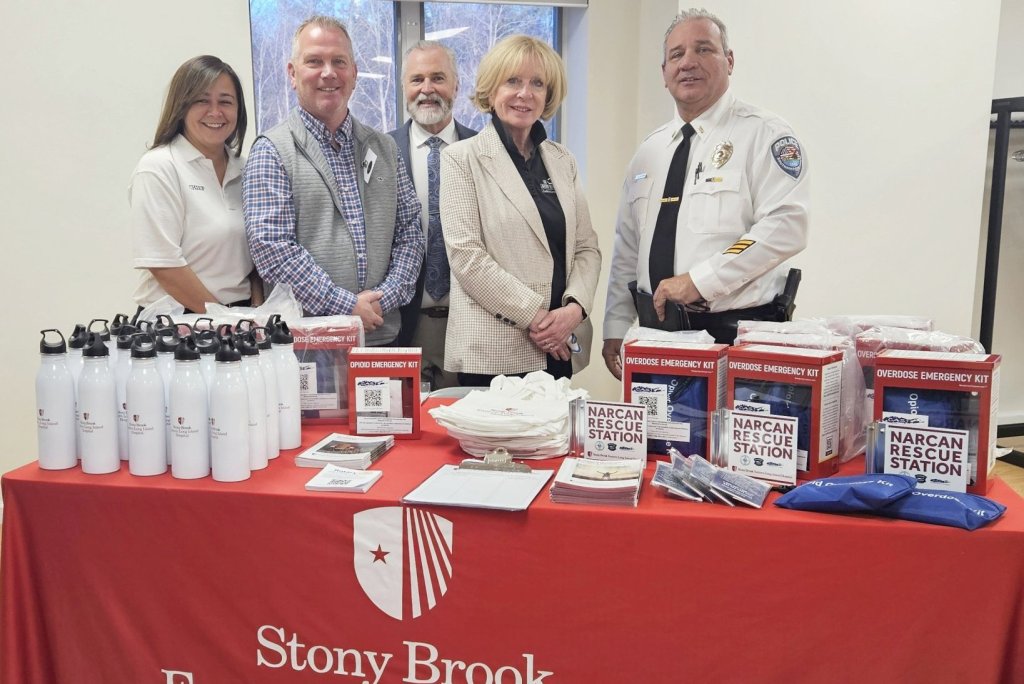

However, last month on Sunday, December 11, a plaque was presented by the American Physical Society at the abandoned laboratory on the site of the Tesla Power Plant, declaring it a “World Historic Site.” In addition, a group called Friends of Science, spearheaded by Jane Alcorn, has been created, which plans to fully restore the laboratory in the next three years. It will re-open as a study house, a museum about Nikola Tesla and his dream. The rest of the 16-acre campus will become the home of a start-up business complex for the new Tesla Science Center. Fittingly, $1 million of the $20 million needed for that restoration has already been pledged by Elon Musk, the founder of SpaceX and Tesla Motors. It should not be too hard to find the rest, given the foresight of this man Tesla and his incredible accomplishments.

Tesla was born in what is now Croatia in 1856 to a priest in the Serbian Orthodox Church. When he was 19 and a student at the Polytechnic Institute in Graz, Austria, he got into an argument with his professor about the use of DC (direct current) motors. He felt these motors would be more efficient if the current were alternating. But how to do it? It had never been done.

As a result of this, Tesla designed and built the first induction motor in order to prove its practicality. It was also his belief that he could create an electrical disturbance in the world that could be used to transmit information and energy, which could be picked up, wirelessly, by small devices. Near his campus residence in Austria, Tesla created several of these charging devices and was able to show wireless transmission of electrical charges at a distance. He could light bulbs with these disturbances, or “gas discharge tubes” as he called them.

In 1884, he came to America with four cents and a letter in his pocket from Charles Batchelor—a former employee of Thomas Edison—who wrote to Edison to introduce young Tesla.

“My dear Edison: I know two great men and you are one of them. The other is this young man!”

Thomas Edison, at this point in his career, was already quite famous as an inventor. He had, in the years before, worked on the development of the telephone (1877), invented the phonograph (1878) and the electric incandescent light bulb (1879)—using DC electric generators. He’d opened a power plant for his electricity in the city of New York (1882).

And he’d also done work himself on eastern Long Island. He’d demonstrated the electric parlor lamp in Riverhead at their new music hall (1881), now the Vail-Leavitt Music Hall. The next summer he went down to Quogue and built a 600-square-foot factory on concrete pylons right on the ocean beach, which would house equipment to separate iron ore—the black slick of metal grains that sometimes washes up onto our beaches—from the regular sand. It failed just weeks after it opened, however—no iron.

Anyway, Edison met Tesla at his laboratory in New Jersey and he hired him. He told Tesla—according to Tesla, anyway—that he would give Tesla $50,000 if he, Tesla, could improve on the DC generators.

Tesla did that, and, again according to Tesla, Edison reneged on what he said he’d pay him. Edison told him that when he became a full-fledged American, he would appreciate an American joke.

As a result of this, Tesla quit Edison and went out on his own, building a lab nearby. Soon, with funding provided by entrepreneur George Westinghouse Jr., he continued his experiments with alternating current to make it more and more powerful.

Tesla demonstrated his work on a stage before members of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers in New York City in 1891. He had two light bulbs on a table three feet apart and wirelessly separated from each other. Turning a dial, both light bulbs lit. It had been done with magnetism creating generators behind metal panels at each end of the table.

Tesla took out dozens of patents on his discovery. He felt he needed to show how it worked on a bigger scale to impress investors, and so, with Westinghouse’s blessing, he went out west and built a wooden building atop Pike’s Peak in Colorado, with one of his small steel magnetic charging domes on the roof. He set light bulbs in windows in the then small town of Colorado Springs nearby, and at his command, he turned on his AC motors and the lightning began to dance. Turning it up all the way, he lit the entire town of Colorado Springs. Above the ball atop the building, an angry blue cloud began glowing in the sky. As a result, after a minute or two, Tesla turned it off and everything went dark again.

With this success, Tesla sought out further funding. J.P. Morgan offered to put up the money for a still larger plant. Tesla returned to New York City in 1900 and in 1901 began construction of Wardenclyffe, this enormous power facility at Shoreham. He hired architect Stanford White—who had done Madison Square Garden and many vacation homes for the wealthy on the East End of Long Island—to design it with the 55-ton metal sphere way up above the building on its steel pylons.

“In this system I have invented, it is necessary for the machine to grip the earth, otherwise, it cannot shake the earth. It has to have a grip so that the whole of the globe can quiver,” Tesla wrote.

Soon, a brick building was created as a power station and the great metal sphere rose on a tall tower nearby. But then, in 1901, Tesla found that the costs had exceeded what J.P. Morgan had already given him.

This coincided with two startling events. One was that the country was falling into a recession and money was tight. The other was that an Italian inventor named Guglielmo Marconi had suddenly demonstrated the use of radio waves for long distance transmission. In late 1901, he built a tall metal tower 300 feet high in Cornwall, England and another such tower in Nova Scotia, and instantaneously transmitted a message across the ocean without wires. Tesla sued Marconi. Marconi, he claimed, had stolen the work of 17 U.S. patents Tesla had on this sort of work. It was true. Yet Marconi had accomplished in reality what Tesla had hoped to do, at far less cost. All you had to do was build inexpensive towers about 10 miles apart from one another. And very soon Marconi’s backers began doing that. That year, the second tower in America was built at Sagaponack, Long Island, and the third one further west in Bay Shore. A few years after that, Marconi won the Nobel Prize for physics.

In this new situation, J.P. Morgan refused to provide additional funding. And no further funding could be had. And so Tesla, around 1907, stopped working at Shoreham. Although nearly completed, it just never opened. The following year, Tesla abandoned Wardenclyffe. It was a bitter defeat, and though now approaching 60, he vowed to go on.

“It is not a dream, it is a simple feat of scientific electrical engineering, only expensive—blind, fainthearted doubting world. Humanity is not yet sufficiently advanced to be willingly led by the discoverer’s keen searching sense…. Perhaps it is better in this present world of ours that a revolutionary idea or invention instead of being helped and patted, be hampered and ill-treated in its adolescence—by want of means, by selfish interest, pedantry, stupidity and ignorance; that it be attacked and stifled…”

If Tesla was getting funding from Morgan and Westinghouse, Edison meanwhile was getting financial backing from a wide variety of investors. Still in control of his company, he soon changed the name of it from Edison to General Electric, and as a result made a fortune. Tesla’s arrangement with Westinghouse did not go the same way. Westinghouse took over Tesla’s company but offered him a hefty profit share. At a certain point after that recession hit, however, Westinghouse said they were about to go bankrupt and could not go on unless Tesla tore up his contract with them where it said they’d give him the profit share. Tesla agreed. Financially, it was the biggest mistake he ever made.

Edison also made mistakes. He’d continued on in his quest for iron ore, even if he didn’t find any in Quogue, and in the years that followed he began a mining operation that operated in five states in the Northeast, but found he could not easily obtain iron profitably. Edison, or more specifically his backers, lost more than $100 million on this.

Edison also tried to create talking motion pictures. Using film projected on a screen while playing a recording on his early phonograph, he developed what he called the Kinescopic system of Talking Motion Pictures, and in 1914 showed it off in Riverhead at the Music Hall where he had demonstrated electrical illumination 20 years before. His films included Julius Caesar and A Scene from Faust, but his system never caught on and he had to abandon it the following year.

Around 1910, after his defeats, Tesla retreated to an apartment on the Upper West Side where, some friends and admirers said, he began to lose his mind. He became fascinated with the number 3. He’d count his steps. He’d only eat specially prepared food, and he’d prepare himself by washing his hands and drying them free of germs and sitting down to eat, all in three motions. Everything had to be in threes. He also began spending time in the park with pigeons. He had names for them. On one particular night, he said, a white pigeon came through an open window at his apartment to sit on his sill and tell him that his work on this earth was done.

He died in his apartment in 1943 at the age of 86.

After his death, a high court, still struggling with the issue of who patented what first, Marconi or Tesla, ruled in Tesla’s favor. And that was that.

* * *

Note: In researching this article, I at first believed that the highly visible 500-foot tower built in Napeague was somehow a project of either Tesla or Marconi. It was not. Other companies around America went into business building towers to transmit Morse code messages to ships at sea. This one was originally built by the MacKay Company in 1927. If you look closely, you will see that the abandoned concrete buildings at its base, which still remain, were constructed in the Art Deco style popular in those years. The two towers in Napeague were built 1,000 feet apart with a wire between them. Both collapsed during the Hurricane of 1938 but were put back up. Then, in the late 1960s, with both towers no longer in use, one of the two was dismantled and carted away. Today, the other is home to osprey and is also in use as a communication tower by the New York State Police.

Another tower on Long Island with an interesting story was built in Sayville in 1912 for the German firm Telefunken. When America went to war against Germany four years later, it was found that Telefunken was transmitting information back to Berlin about American ships at sea, including the giant cruise ship Lusitania, which German submarines torpedoed in 1915 off the Irish coast, killing 1,200 passengers. And so, the U.S. Navy seized the Sayville tower and, after the war, turned it over to MacKay. At that height, it was considered MacKay’s flagship tower during those years.