Unsolved Murders: Robert Durst, Real Estate Moguls, Ad Men and the Dark Side

A picture of Nick Chavin, a friend I haven’t seen in 25 years, was on the front page of The New York Times this past Saturday. He’s a sensational new witness in a pre-trial examination involving millionaire Robert Durst. Durst, as you know, is serving time for other things but so far has not been convicted of murdering anyone, though he was around three people who, while he was around them, either vanished or got killed. They were his first wife (1982), his next-door neighbor (1994) and his friend Susan (2000).

Chavin, according to The New York Times, was a close friend of Robert Durst, going back to when they were in their 20s. Durst was best man at Chavin’s wedding. Now he was offering sensational testimony about what he knew from all those years ago.

It did occur to me, reading The New York Times on Saturday, that at one point all these years ago, off-handedly, he had suggested I interview Robert Durst for the paper. Durst didn’t have a house in the Hamptons, however, so I didn’t. But I did interview Seymour Durst, Robert Durst’s father, at Nick’s suggestion. And I also interviewed Nick, who did have a house in the Hamptons.

Nick Chavin, at the time I knew him, was the co-owner of the largest real estate advertising agency in New York City, Chavin Lambert. At the time, this was in 1990, I was actively selling advertising for Dan’s Papers, often roaming around Madison Avenue looking for a sale. It was natural I came to meet Nick Chavin. I found him a funny and fascinating person. That year, he had a home in Montauk and another on Central Park South. I still recall that when I asked him how he had met his wife Terry, he told me he had a summer share in a house in Westhampton Beach that year, and one Saturday night, he came home late to the house but couldn’t find the key to the front door. So he’d gone around back and climbed through a kitchen window to land in the sink where, as it turned out, a pretty girl was doing the dishes at that hour. He married her.

For advertising, and for interviews I was writing for Dan’s Papers and a future book (it came out in 1995, Who’s Here in the Hamptons, published by Pushcart Press), he suggested I meet some of the major players in real estate in the city. He knew almost all of them. My interviewing them would help them, me and even him. Who wouldn’t want to be profiled in Dan’s and collected in a book?

I recall we went over who I could contact at several lunches at the Harvard Club in New York. I wrote the names and contact numbers down on a pad. They should either have houses in the Hamptons or at least come out to the Hamptons sometimes.

Through Nick I came to interview Barbara Corcoran (she was thinking of retiring,) Donald Zucker, Clark Halstead and Jerry Cohen (“There are two of them, both important,” Nick told me. “One is very flamboyant and has no connection with the Hamptons. The other has a house on Shelter Island. A really personable guy.” I interviewed the latter.)

He thought it important I interview Louise Sunshine, and I called her several times but nothing came of it. He suggested Mort Zuckerman, Stephen Ross of Related Companies, Donald Trump and Harry Helmsley.

“The Durst Organization is very important in New York City,” he told me. “It’s a family business and they own a ton of buildings. I could get you an interview with Robert Durst, one of the sons. Or the father, Seymour Durst, who is about to retire soon. But none of the Dursts comes out to the Hamptons.”

I did interview Seymour Durst anyway. He was the man who had put up all the signs around the city that in illuminated lights revealed the constantly changing national debt going up and up and up. He also bought little ads on the bottom of the front page of The New York Times that served as alarming notes about that.

It’s important to note at this point what I knew and didn’t know about the Durst family. This was in 1992. Robert Durst’s wife had vanished 10 years before. I knew nothing about that.

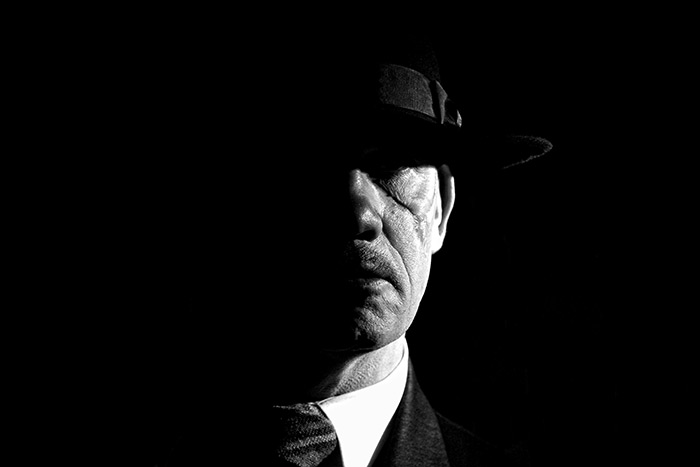

I interviewed the patriarch of the family, Seymour Durst, at his home, a brownstone on the Upper East Side. Seymour was a small, elderly man who wore a suit and tie and moved slowly and talked softly. And he was fascinating.

Inside this dark, dusty five-story brownstone—he took me through all five floors, very slowly—he had assembled, on every floor, hundreds of mementos of the recently dismantled and formerly sleazy Times Square. There were signs advertising peep shows, adult bookstores, 24-hour Girls! Girls! Girls!, movie theaters, dance halls, fortuneteller booths and live shows. Much of it, Seymour told me, came off the fronts of buildings that he owned.

“It’s Americana,” he told me. “Times Square is changing. These things need to be saved.”

He also had a collection of more than 15,000 books all about New York City. Halfway through the tour, he introduced me to a middle-aged woman sitting at a desk.

“She’s the librarian, doing the archiving,” he told me. “This is probably the largest private collection of books about the city of New York. Major libraries in the city are courting me to leave the collection to them when I pass on. We shall see.”

I spent an hour with Seymour Durst. There was something very odd about the whole thing. This was his home. But nobody lived there but him. There was no kitchen, no bedroom that I could see. It was cold and chilling in this brownstone. The shades were drawn. Where was everybody?

Somewhere, afterwards, I learned, there had been some kind of tragedy in his family, possibly with his wife. I never asked him about it that day and he never told me. He also never talked to me about his business.

As he walked me down the stairs to the front door, I thanked him and told him of one particular book in his collection I liked and he said “come back any time.” And I did, twice, to read it, read others and see him.

My friendship with Nick Chavin lasted about 10 years. In the real estate dip in 1999, Nick told me he and his partner were discussing a parting of the ways. I continued to see him, several times at his home for drinks, but then after that Nick dropped out of sight. The phone number I had for him was disconnected.

According to the Times story on Saturday, Nick had been interviewed numerous times by the authorities about his friendship with Robert Durst. He’d said repeatedly that Durst’s friend Susan—who the Times said Nick had known even before he knew Durst—said Durst killed his first wife. At first he said he didn’t believe her, then later he wasn’t sure what to say to the authorities. Then Susan was dead, too. It was time, Nick said, to tell what he’d come to believe was the truth. According to Nick’s testimony, Durst had, in private, admitted to killing Susan. “It was either her or me,” Durst had told him. Defense attorneys are claiming Nick is now making this up.

Durst, meanwhile, will not talk to him. I hope Nick, wherever he is, is okay.