The Ham Tons: Documenting the Changing Names of Hamptons Villages

In several places around the country, there are gaggles of villages called “Hamptons.” In Massachusetts, for example, there’s an Easthampton, a Westhampton, a North Hampton and, spilling over into New Hampshire, a South Hampton, a Hampton and a Hampton Beach. Every one of these names is spelled slightly differently from the names given for Hamptons here in the Hamptons.

And of course, none of them has the panache of “The Hamptons.” That’s here on Long Island. Everybody knows that.

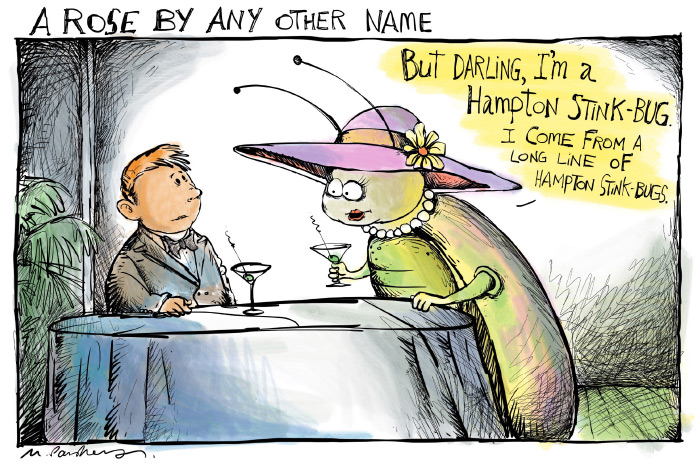

Who doled out these names so nobody would get mixed up? I don’t know, but I thought it would be a good public service to write about the Hamptons here on Long Island and how they got the names that they did. Many of them started out as a “Hampton” and continue so to this day. Others didn’t start out as a “Hampton” but became one. A few WANTED to become a “Hampton” but failed. None started out as a Hampton and wanted to later get out of being called that. Interesting.

First, however, I should start with Southampton, the dowager of the Hamptons, the Hamptons through which all others flowed, the first Hampton and the one that set the tone for all Hamptons that came afterwards.

Southampton was founded in 1640 by settlers from Lynn Massachusetts, who had a royal charter from the Earl of Stirling in England. He was to be paid four bushels of the finest Indian corn every year. There was also a proviso that 1/5 of all the gold found on the aforementioned property would belong to the King and had to be shipped to him forthwith. This went on until the Revolution ended all that 136 years later. But Southampton, from the beginning, was never anything else but Southampton. I have, however, seen a Long Island railroad map where the stop is called South Hampton.

English families from Southampton soon came eastward and in 1644 formed a new village they called Bullshead at the headwaters of Sagg Pond. When a bridge was built across Sagg Pond—primitive at first but more permanent in 1686 by Ezekiel Sandford— the village of Bullshead became known as Bridgehampton. In researching this town, I have found that among the famous people who lived in Bridgehampton back then was a notorious criminal named Stephen Burroughs. He helped found the Bridgehampton Library in 1793 and donated his books. He’d gone straight, I guess.

Going on eastward, settlers from Connecticut founded the Village of Maidstone in 1648. After a few years, however, it received a patent to change its name to East Hampton since it was East of Southampton and to get there you had to pass through Bridgehampton. In 1657, East Hampton became a colony of Connecticut. It later reverted to the New York colony. For many years, the name was spelled different ways in different contexts. Two postcards from the early 1900s call it Easthampton and East Hampton. There are history books where it is spelled East-Hampton. An section in a book called Long Island History by Peter Ross, published in 1902, refers to it two ways, as East Hampton and Easthampton in the same piece. According to East Hampton Librarian Gina Piastuck, the name might have been finally settled upon as East Hampton by the town newspaper. In its first issue in 1885, the name of the paper is The Easthampton Star. On February 13, 1886, it’s called The East-Hampton Star, and in 1887 The East Hampton Star. The hyphen returned beginning in issues in 1888 and it was that way until 1901 when it finally decided it would be The East Hampton Star.

“It’s hard to tell if anyone really agreed on one official spelling,” Piastuck wrote me.

Going westward from Southampton, a group in Connecticut arranged to buy a large tract of land west of the Shinnecock Canal, which they called the Quogue Purchase. Colonists settled on this tract beginning in 1666, some in a place called by the Indians Ketchabonac. A post road between New York and Southold was established in 1765, which ran through what was stilled called Ketchabonac at that time. At some point, the name was changed to Westhampton. In 1800 it was changed again, this time to Westhampton Center. It was changed yet again in 1890 to Westhampton Beach, about the time that wealthy New Yorkers began coming out to build great mansions there. “Beach” sounded better, I suppose. The village of Westhampton Beach was officially incorporated in 1928. Huckster P. T. Barnum is a famous resident, having established the Howell House on Main Street around 1900. Ten years after the incorporation of the village, it received a direct hit from the Hurricane of 1938, widely considered the worst natural disaster of the 20th century. Twenty-eight people died, and almost every mansion on Dune Road was carried across Moriches Bay to pile up on the bayfront shores of mainland Westhampton Beach.

The hamlet of Good Ground was founded in 1740. It’s a wonderful name. Some accounts recall that, in 1743, there was a smallpox outbreak. But Good Ground recovered.

Good Ground soon became the central shopping district for Canoe Place, East Tiana, Newtown, Ponquogue, Rampasture, Red Creek, Squiretown, Southport, Springville, and West Tiana. But in 1922, Good Ground decided it should become a “Hampton” and in what is officially known as an amalgamation, the townspeople changed its name to Hampton Bays. However, today high up on a concrete wall of a former hardware store on Main Street is inlaid the name Good Ground.

The most recent Hampton to pop up was on a narrow peninsula of land that until 1938 was an unnamed part of Fire Island in Brookhaven Township. When that hurricane broke through the barrier beach that year and never healed—becoming the Moriches Inlet—this strip of land, about 1.4 miles long and at places only 300 yards wide—was annexed by the Town of Southampton. During storms in the 1960s and 1970s, the ocean broke through from the bay cutting off all municipal services, and the few residents whose houses had not been blown into the sea decided to incorporate it as a village. They named it the Village of West Hampton Dunes and sought federal help. Today, with a permanent population of 58 people, it is the least populated of any village in the Hamptons. Nevertheless, electricity, sewage, phone and roads were restored and the new village became accessible again and soon thrived.

Here are a few communities on the South Fork of Long Island who tried to become a “Hampton” but failed.

In 1899, a group of wealthy New Yorkers who had summer homes in Shinnecock Hills wanted to change the name of that section to Hampton Hills because it would sound more exclusive. When they looked into it, they found that could happen if the permanent residents signed a petition to make it so. But none of them was a permanent resident. Then they realized, there was one permanent resident. He was Ralph Terwilliger, the postmaster of the Shinnecock Hills Post Office who lived alone above the post office—which also was the Shinnecock Hills Railroad Station. He lived there all year around and in the summer put the mail in their boxes and in winter forwarded it along to other addresses. So they went as a group to his office and asked him. Would he please vote for the change?

“Nope,” Terwilliger said.

As I recall, in the 1970s, the community of Bellport tried to change its name to “Hampton Port,” but they couldn’t agree on whether they wanted to do that or not and the effort failed.

With that I conclude my survey of all the places out here that call themselves, uh, whatever.