May 20: The Day the Amagansett Coast Guard Station Re-Opens as a Museum

The historic Amagansett Coast Guard Station, which has undergone a meticulous eight-year restoration, will have its grand opening ceremony as a new museum on Saturday, May 20. On hand will be personnel and bands from the Coast Guard, local grade school choirs, officials from the Suffolk County Sheriff’s Office in Riverhead and other dignitaries. The public is invited, free of charge.

This old Coast Guard Station has weathered a fabulous history, which includes Nazis, 300 Irishmen, shipwrecks, prisoners from the Riverhead Jail and the time this three-story building, oceanfront, was sold to a private citizen for $1 and was moved away for 40 years.

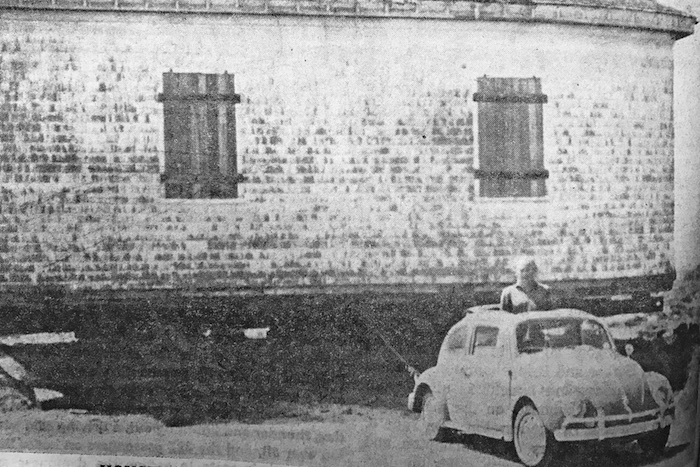

The photograph you see at the top of this story is of me, standing up through the sunroof inside a Volkswagen bug, appearing to be towing this massive 6000-square-foot Coast Guard station up Atlantic Avenue. It’s part of this history.

It’s a rather famous photograph, having appeared on the front page of Dan’s Papers the week after it was taken, and then briefly in the 2015 Ocean Keeper documentary about the Coast Guard Station. I think there’s a copy of it at the East Hampton Historical Society. So I suppose I should start with that.

A week before the picture was taken, I had learned that the old oceanfront Coast Guard Station, which had sat abandoned at the end of Atlantic Avenue for nearly 25 years, had been sold to a man named Joel Carmichael, of Amagansett, who owned an empty plot of land on Bluff Road about a mile away. He’d bought the building from the Coast Guard for $1 and planned to tow it up the street to his land to convert it into a private home. I wrote about that in Dan’s Papers at the time. This was in 1966. The following week, I learned that movers, working on the old Coast Guard Station using heavy equipment, had gotten the building off its foundations and moved 100 feet to the east onto heavy railroad ties set up there temporarily in the middle of Atlantic Avenue.

At the time, Dan’s Papers was six years old. I had two employees, a secretary and a guy named Rameshwar Das who lived in Barnes Landing and who wrote, took pictures and helped with delivery. So he and I, along with his camera, started out in his Volkswagen Bug down Atlantic Avenue early that morning to take a picture of it sitting in the road. When we got there, we

saw that the building overflowed both sides of Atlantic Avenue. Nobody was around. The building was just right there, with an enormous curled up maritime cable attached to the front and facing us, just waiting to be tied up to the back of the little Volkswagen bug so it would look like we were pulling it. Ha. Well, we were young guys then.

Later that day, after we were gone, the house-moving crew came back and, after more heavy lifting, got this Coast Guard station up Atlantic to Bluff Road, where, for the next forty years, Joel Carmichael and his wife lived in it as a private home and raised a family in it. Two of Joel’s granddaughters, Felicity and Deborah, would go up into the Coast Guard tower to paint pictures of the waves and clouds. Joel had a study on the second floor, which had been the Coastguardsmen’s barracks bedroom. The first floor consisted of the Coast Guard Keeper’s private quarters, a kitchen, a ready room, a flight of stairs up and, in an attached 30 x 34 foot garage, a surfboat with oars that was heavy enough for a crew of eight to row through the surf and into the ocean, a smaller lifeboat and other lifesaving equipment that included a “breeches buoy.” This was an iron cannon on wheels from which a rocket could be fired out to sea. If a ship was in distress on the rocks and breaking up in the surf, a rope could be attached to the back of the rocket, the contraption pushed down to the water’s edge and turned to aim just above the top of the ship. When the rocket was fired it would travel over the ship, but the rope it was carrying behind it would settle in the rigging where the ship’s crew could grab it as it came down, tie it to a mast, and with that arrange for a rope and pulley affair to be hauled out bringing supplies out and passengers back in, sitting in breeches buoy chairs over the ocean and back to land.

In 1966, the Coast Guard station was empty of all of this. The Carmichaels made a big living room space out of the garage and entertained there sometimes. Forty years went by until, in 2006, Joel died and the family decided to sell the Coast Guard Station to the Town for $1, so it could be hauled back to where it had come from after all those years.

The predecessor to this structure was built in 1849. After renovations and additions, much of it was then replaced with this newer one, built in 1902. You know how each local community has a volunteer fire department? Well, back then, communities had not only fire departments, but also Life-Saving Stations on the ocean manned by about 40 volunteers. About 30 such stations were built on Long Island. Here, in addition to the one at Amagansett, there were others at Montauk Point, Ditch Plains, Hither Hills, Napeague, Georgica, Mecox and Shinnecock.

On the afternoon of August 25, 1841, two years after the first Life-Saving Station was built in Amagansett, the ringing of church bells downtown alerted the volunteers to a ship coming up onto the beach less than a mile west of the Atlantic Avenue station. The ship was the sloop Catherine, out of Liverpool, and onboard were 300 Irish immigrants—men, women and children—coming to the New World and the port of entry in New York City. The ship would not make it. It had foundered in a storm.

At Amagansett, there was no need for the breeches buoy or the lifeboats. The ship had slid right up the beach. The water was warm. All 300 passengers were rescued over the side, along with 298 of the 300 sea bags that contained the worldly possessions of these passengers. Two sea bags were deep down in the hold and were lost when the ship broke up.

At that time, every town had a Wreckmaster who was in charge of how the rescue would be carried out as far as salvage was concerned. With the Life Saving Station having been opened just two years earlier, this was the first large rescue of a ship foundering at sea there. The East Hampton Wreckmaster, Jeremiah “Jed” Conkling, a part-time government official, had been appointed just as the Life-Saving Station was completed and worked with the life-saving battalion. He arranged for the passage of the passengers to Sag Harbor—a thriving whaling town at that time—where the new arrivals were temporarily taken in by residents of the community. Conkling then arranged for their subsequent passage to New York. Six days after the wreck, the Sag Harbor Corrector newspaper reported that a steamer called the Achilles had arrived at Long Wharf towing a small lighter called the Martha Stewart. The anchor, chains, rigging and sails from the Catherine were put on the Martha Stewart, the passengers were boarded on the Achilles and off it all went to New York to complete their journey.

Three passengers from the ship chose to remain on the East End. They were Patrick Lynch, who had intended to go on to San Francisco and the gold rush, but decided he liked it out east. The others were Captain Heselton, the commander of the ship that foundered, and his wife. Two years after the shipwreck, a notice was posted in the Sag Harbor Corrector by the captain, thanking the people of Sag Harbor for their kindnesses in helping care for his wife in her final days. She had passed on.

In 1915, the federal government created the U.S. Coast Guard. It replaced the Revenue Cutter Service and the Life-Saving Stations and took over from the volunteers to provide many of the same services, but now with professionally trained military men. When World War II ended in 1945, the Amagansett station was decommissioned and abandoned, leaving it empty for the next 20 years. Soon, with vandals getting at it, the Town decided it would be a good thing to get this wreck off the beach and so sold it for $1 to Joel Carmichael in 1966 with the proviso that he move it.

Certainly the most dramatic event that took place at the Amagansett Station occurred at 12:05 a.m. on the night of June 13, 1942, in the middle of World War II. A group of four Nazi saboteurs came ashore in a rubber boat from a German submarine that dark night just to the east of the Coast Guard station.

At the time, the U.S. military was expecting just this sort of incursion and so had placed an after-dark curfew on all beaches and given the Coast Guard the task of providing foot patrols 24 hours a day at 2 hour intervals. It was on one such patrol that 19-year-old Ensign John Cullen, walking along the ocean with a flashlight at night, stumbled upon these saboteurs burying wooden boxes in the sand. As he got there, one of them strolled out to talk to him. Speaking English with a foreign accent, he gave Cullen $300 in cash and told him to run away and forget he ever saw them. If he didn’t do that, the stranger told him, he would be killed for having discovered this secret government mission.

Cullen, seeing the rubber boat on the shore and two sailors with machine guns guarding it, took the money and ran back to the Coast Guard Station.

As a result of this, a company of heavily armed American soldiers camped in the dunes of Napeague arrived in military trucks to join up with about a dozen Coast Guardsmen who had bravely gone out with rifles to find whoever had done this. But by this time the four saboteurs had gotten off the beach and away and into the woods, eventually making their way to the Amagansett Railroad Station where they took a 6:59 a.m. train to Manhattan.

When they got to the city, the lead saboteur, the one who had told Cullen to take the money and run, turned in all the others to J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI. The boxes contained dynamite, fuses and other explosives. The Germans were supposed to carry out terrorist acts. This encounter on the beach just east of the Coast Guard Station surely resulted in the saving of many American lives.

I have written a book about this encounter called The Night the Nazis Landed, and advance copies should be out this summer.

I did say that jail prisoners were involved with the Coast Guard Station. After the town bought the Coast Guard Station back from the Carmichael family for $1 in 2006 and towed it back to its original site, a local citizens group was created called the Amagansett Life-Saving and Coast Guard Society. Its goal was to raise money and restore the Life-Saving building as a museum. Among those involved were Isabel Carmichael, David Lys, Ben Krupinski (the builder), Robert Hefner and many others. It took a decade to complete this work. And now it’s done. I talked to David Lys about it, and he told me that the Riverhead County Jail provided them with volunteers. Prisoners on good behavior were now rated as “trustees” and could come out every day and, under guard, scrape paint off, sand the floors, rebuild the walls and ceilings. I didn’t see them myself, but I was told they wore their orange jail suits with the word PRISONER on their backs while they worked.

“One day the Good Humor truck came, and so we gave them money and there they were, a group of them in their orange suits, eating ice cream cones standing next to the snack truck. Everyone was so happy.”

Whew! See you May 20.

Incidentally, about once every five years, the ribs and beams of the wrecked Catherine, now nearly 170 years old, appear in the sand at very low tides where she came ashore. They remain visible for a few days, then get covered up again by the ocean.