Angry Birds: Hamptons Least Terns Express Themselves for Being Overlooked

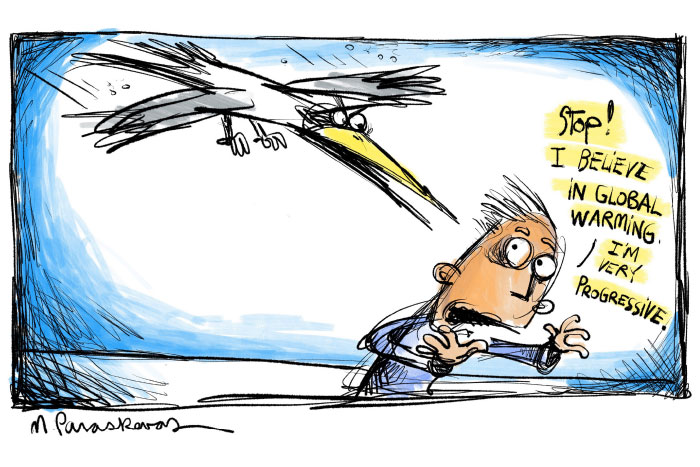

At a party the other night, I ran into Ken Warner, who has an oceanfront house in Quogue. He told me they’ve got a big problem on the beach there with a bird called the least tern. These birds swoop down and try to attack people as they walk down the paths to the beach.

“It’s the strangest thing,” he said. “It’s never been this bad.”

I told him the least tern situation on the beach in East Hampton was much better this year. In prior years, we’ve had least terns swoop in like that. They come across the sky, angry, usually in groups of three or four, and they dive bomb at you, one at a time, fluttering their wings in your face—scaring but not hurting you. They are telling you to get the hell out. Usually it happens in the morning, when they are looking for breakfast—little bugs that swarm in the sky. They just don’t get it— that we’re not competing with them for bugs.

As we talked about this phenomenon, we realized there was a kind of correlation between these little birds attacking in one place one year but not in another, and the number of nests on the beach built by another small bird—the piping plover. Piping plovers share the shoreline of our beaches with least terns. It’s easy to tell them apart, though. In East Hampton last year, when we had many piping plover nests, we had many least tern attacks. But now, with less of a problem in East Hampton, it’s worse in Quogue. Could these least tern attacks be related to the large numbers of piping plover nests?

You do see the least terns and piping plovers intermingling with one another, but you never see the two species friendly-like to each other. They both skitter along at the edge of the surf, running up the sand and then back down as the surf comes in and out. But they do seem to get along.

The big difference between the two species on our beaches is caused by a different species entirely—human beings. Humans have decided that piping plovers must be protected. They are an endangered species and so humans have made them the poster child of endangered species, entitled to special treatment. We’ve made laws that will bring you a big fine if you mess with a piping plover nest. We do other things to pamper piping plovers. We erect snow fencing with “keep out” signs on it surrounding every piping plover nest we find along the entire 60-mile stretch of beach in the Hamptons during the nesting season. In some places, though, there may be crowds of nests, which almost completely block access to the water for humans for miles, and we can’t have that. And so we make an exception and build pathways for the humans to tiptoe through in order to get from behind a nest all the way into the water. These pathways are bordered by more snow fencing. They appear about every seventy five yards or so.

Fact is, humans do not give the least terns the same special treatment. And the least terns know it. They see it right before their eyes. Who can miss a cold shoulder?

What we believe is happening here is that the least terns get angry when they see lots of plovers around getting this special treatment and they’re not. Who can blame them?

Furthermore, there are the names humans have given these birds. The name piping plover is sweet sounding. If the piping plovers were a wine, a connoisseur would declare them to be musical, delightful, sweet smelling and beautiful with perhaps a hint of lilac. If a connoisseur were to describe the terns, he’d say they are smelly, dumb and boring and they’re a bother to have to kick out of your way as you walk along the shoreline, and this is the least of them, the runt of the litter, the least terns.

Pay a little attention to the least tern. Pat it on the head, give it a manicure and a pedicure, throw some fencing around its nests and change its name to something nice—The Shore Sentinel perhaps.

That should put a stop to the dive-bombing.

This is what can happen if you have a few drinks at a party.