Dead Nazis: Tombstone Tribute Found to Nazis Who Landed at Amagansett

The Washington Post ran a story on June 22 that is of interest to the people of Amagansett. The headline was “Six Nazi spies were executed in D.C. White supremacists gave them a memorial—on federal land.”

It’s quite a story. And it’s quite a piece of granite.

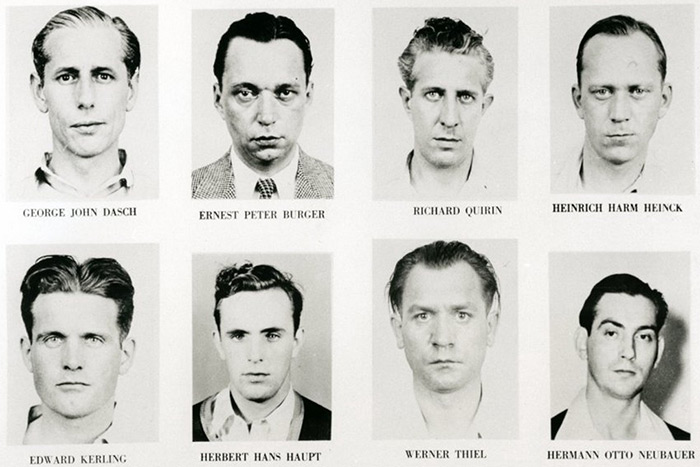

During World War II, Hitler launched an operation intended to terrorize America by sending saboteurs here to blow things up. They came in submarines and landed on our shores. The first four, together with explosives and $85,000 in $50 bills in a valise (more than $1 million in today’s money), arrived in a fog at the beach in Amagansett just past midnight on June 13, 1942. The next four landed on Ponte Verde Beach in Florida four days later.

Seven of the eight terrorists were proud members of the Nazi party. But the eighth, George Dasch, was not only not a Nazi—he was, incredibly, the leader of the operation. His plan after wading ashore from the sub’s rubber boat that night in Amagansett, was to turn all the others in before they could do any harm. And he did that.

From the Amagansett railroad station, he led the terrorists by train to Manhattan, then left them there so he could attend an important meeting—which he said to the others would be with Nazi sympathizers but was instead with J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI in Washington—where he turned over the money, told the FBI where the seven others were and watched them get arrested.

Things didn’t quite work out the way Dasch had intended, however. After the FBI rounded up the others, they arrested him too, squirreling him away in a prison’s solitary confinement wing so Hoover could take full credit for the roundup.

President Roosevelt was shocked that these terrorists had come through our shoreline defenses. He gave them a trial—a real kangaroo court trial lasting just 10 days. American generals did what they were told to do. The Supreme Court obeyed the President’s wishes, laid down and declared it all perfectly okay. Then the decision came down.

On August 6, 1942, by President Roosevelt’s order, six of the eight terrorists died in the electric chair. It was the largest mass killing of people in prison in one morning before or since. And it took place just 56 days after the landing. Dasch was not one of those executed, and neither was another German—a Nazi soldier who came ashore but then helped Dasch and the FBI round the others up. These two received long prison sentences and were never allowed to be interviewed. Three years after the war, both were deported back to Germany in handcuffs and let loose with $50 in their pockets, together with the advice that they would never be allowed to return to America and if they told anybody what had happened they would be arrested again.

I have been working on a book about this incident in my spare time—it’s even been optioned for a movie—but I am not done writing it. So it is still not ready for prime time.

However, I can tell you the backstory about what the Washington Post thought was big news. It is a lesson in not being able to throw anything away.

After the six terrorists were electrocuted, their bodies were taken to the morgue in an Army medical center near the prison, and then, in simple pine coffins, were driven in the back of a truck to a remote potter’s field, by the side of a garbage dump, and buried. It was supposed to be a secret, but it was in the Blue Plains hillside along the southern border of Washington, D.C., and when the wind blew the wrong way, it stank. After a brief ceremony with a priest and a minister, the six Nazis were buried under six wooden stakes that had the numbers 276, 277, 278, 279, 280 and 281 on them. To separate these bodies from others who had not suffered such a dreadful end, the site with the Nazis was sectioned off with a six-foot-high wire mesh fence.

According to my research, some years later, at a time when a garbage recycling plant had replaced the garbage dump, hikers walking through the woods found that someone had moved aside the wire fence and placed a handsome granite tombstone inside, where the terrorists were buried, praising their memory. Learning of it, outraged authorities ordered the granite removed. Then a chain-link fence was erected on the site with a locked gate so it would not happen again.

After that, nothing happened for 50 years.

The Post article—which starts off telling about some utility workers laying cable who recently discovered the monument in a ditch at the bottom of Blue Plains—is based a good deal on an interview with a man named Jim Rosenstock.

Rosenstock had worked in resource management for the National Park Service and says that this offending piece of granite was on federal land owned by American taxpayers. After years of the Park Service research into the matter, they eventually dispatched a forklift to the ditch to remove the bigoted monument and bring it back to one of their storage buildings—they don’t want to name which one it is, perhaps for fear some Neo-Nazi might steal it. And the story, according to the Post, is that this hate message had gone all this time unnoticed on property owned by the taxpayers. Had people been holding secret meetings there?

The monument measures 31”x26”x8” and is carved with this inscription:

In Memory of the Agents of the German Abewahr Executed August 8, 1942

Herbert Hans Haupt

Heinrich Harm Heinck

Edward John Kerling

Hermann Otto Neubauer

Richard Quirin

Werner Thiel

Donated by the N.S.W.P.P.

Rosenstock has done a little sleuthing about the N.S.W.P.P. Between 1967 and 1975, the founders of the American Nazi Party found themselves on a downhill trajectory since their founder—who’d renamed them the National Socialists White People’s Party—was murdered. They were going out of business. Bingo.

Rosenstock told the reporter for the Washington Post that somebody suggested taking a sledgehammer to the granite. Rosenstock said that this is not what environmentalists and historians do. They save things.

So it’s still around, but somewhere else.

The first time around on Blue Plains, those who removed it were apparently never told where it should go. It weighs over 200 pounds. A good guess is that a group of workers just picked it up and walked it down the hill to the river and threw it in, upside down.

So here it is again, an unwanted bigot’s message, and it’ll probably be rediscovered in another 50 years, who knows where. Like I said, they won’t tell us which building it’s in. But it’s there somewhere.

I have often written about the difficulties involved with heavy things. A lot of fuss and feathers happens around them every once in a while, they are then forgotten and, later, they are discovered by some new generation that hadn’t known they were there and so the cycle starts up again.

And life goes on.