Pollock-Krasner House Explores 'Abstract Expressionism Behind the Iron Curtain'

In the heyday of Socialist Realism, the art doctrine which glorified the depiction of communist values, artists in Eastern Bloc countries under the Soviet thumb were essentially required, often on pain of imprisonment or worse, to adhere to official, politically dictated content of collective, rather than individual, artistic vision. One might have been surprised, therefore, to discover anything remotely similar to the Abstract Expressionist artwork for which Jackson Pollock became famous.

It certainly surprised Helen Harrison, director of the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center in Springs, when she visited the Vienna Museum of the Modern Art in 1992 and saw such work that was created during that time period. “I had thought—naïvely, as it turns out,” Harrison writes in the catalog that accompanies the Pollock-Krasner House’s new exhibition, Abstract Expressionism Behind the Iron Curtain, “that artists who didn’t conform had to emigrate if they wanted to pursue unsanctioned forms of expression.”

Many did. But those who stayed, Harrison notes, “in spite of censorship, were conversant with trends of international modernism—including Abstract Expressionism…either through personal journey to the West or through traveling exhibitions that went to Communist countries.” In fact, the catalogue contains a photograph of Pollock’s 1947 painting “Cathedral,” on exhibit at the National Exhibition of American Art in Moscow in 1959.

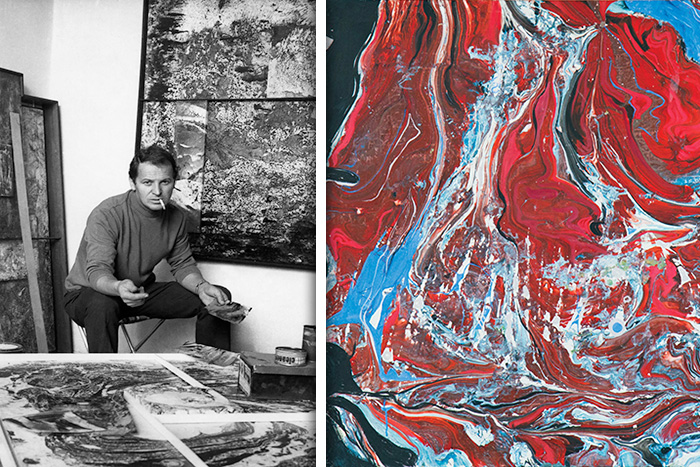

This particular exhibition really began in 2014, when Joana Grevers visited the Pollock-Krasner House and proposed to Harrison an exhibition of the work of the Romanian Abstract artist Romul Nuţiu (illustrated at top of page).

Grevers explains in the foreward to the catalogue that, as a member of the acquisitions committee of the then-new Contemporary Art Museum in Bucharest, she first discovered Nuţiu’s art in 2007. Of the 500 applicants for inclusion in the new museum, Nuţiu stood out.

“His work was purely abstract and of a very high quality,” Grevers writes. When she visited the artist’s studio, she discovered it “full to the ceiling with…decades of expressionist abstract works in a chaotic atmosphere.” When Nuţiu died in 2012, Grevers organized a retrospective of his work at the Museum of Art in Timisoara and, given its success, decided “to travel to neighboring countries to find out if there were other like-minded artists from the first post-war generation.”

Harrison already knew there were. During a 2005 conference sponsored by the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center, she had discovered how deeply the art form had penetrated the Soviet Union and its satellites. “The fact that much of their work was virtually unknown in the United States,” she writes, “suggested that, while the Russian avant-garde and dissident artists have since been recognized, there was a much wider field to explore.” She suggested Grevers expand the subject to include more Eastern European artists.

“Then the adventure began,” Grevers writes. She traveled throughout the former Eastern Bloc to Prague, Łódz, Zagreb and Ljubljana seeking out Abstract Expressionists. In 2015 and 2016 she returned with samples from Edo Murtic (Croatia), Jan Kotíc (Czech Republic), Andrej Jemec (Slovenia) and Tadeusz Kantor (Poland). Add Nuţiu, and you get Abstract Expressionism Behind the Iron Curtain, which will be on display at the Pollock-Krasner House through October 28, 2017.

That’s how it came together, but what is it? Or, more to the point, how does one look at Abstract Expressionism? Do the seemingly incoherent visual representations—a drip of paint here, a jumble of lines there—merit the coveted term, “art?”

In another essay included in the catalogue, Philip Rylands, former director of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, writes, “Abstract Expressionist art folds into itself…the encapsulation of feeling and the language of the spirit—a spirit specific to the time of the work’s production: the Zeitgeist.” He goes on to explain a “work of art is the nexus of two different situations: first, the outpouring of an emotion by the artist…and it must then cause the same emotion in the sympathetic or susceptible viewer.”

Art, it would seem, is in the eye of the beholder—one who is capable of having an appreciation and/or understanding of the world in which the piece was created.

“Might the glow of light from behind Jemec’s charred barricades be metaphorical for a message of hope?” he asks. Jemec’s paintings on view were created in 1960 in his native Ljubljana, part of what was then Yugoslavia under the Tito dictatorship. (To be fair, some historians argue, Tito’s was a benevolent dictatorship.) Did Jemec see a light from behind the iron curtain? It seems the only reasonable answer to Rylands’ question, given the proper historical context, is yes.

Rylands asks a similar question of Kantor’s “Chelsea.” “Does the standoff between the organic and the mechanistic…lend menace to the figure on the right: is it predatory? If squeezed would it detonate? Or has it already done so?” What then hides behind the surface of the other paintings on exhibit? Pollock himself said, “Technique is just a means of arriving at a statement.” What statements could only be expressed abstractly behind the Iron Curtain? If putting yourself in the headspace of a mid-20th-century Eastern European artists seems a daunting or impossible task in 2017 East Hampton, don’t worry. The exhibition’s catalogue also includes short biographical sketches of each artist and another informative essay, “Painting and Politics,” by Charlotta Kotíc.

It seems viewing art isn’t supposed to be easy. Abstract Expressionism, it appears, forces its viewers to ask themselves uncomfortable questions, to confront uncomfortable situations, both of which might engender uncomfortable realizations. Yes, art is in the eye of the beholder, but there has to be something behind the eye to understand what it is seeing.

“We the viewers are,” Rylands says, “on our own.” So put down the cell phones, forget about today’s political bombshell, make a date with friends and think about art. What better way could you think of to spend a weekend?

The exhibition is on now through October 28 at The Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center at 830 Springs Fireplace Road in East Hampton. Call 631-324-4929 or visit stonybrook.edu/pkhouse for more information.