Park? A Proposed Sag Harbor Park Is Parked by the Side of the Road

The Village of Sag Harbor is breathlessly awaiting the creation of a new public park. It is to be called the John Steinbeck Waterfront Park in honor of that Nobel Prize winning author who lived the last 13 years of his life here.

Located behind the 7-Eleven, the park will have an arc of beach and an acre of lawn and pedestrian paths smack in the middle of downtown, right on the harbor, overlooking the sunset over boats. Pedestrians will be able to stroll a hundred yards from Long Wharf by walking around the abutment under the bridge to North Haven. A second access will be from Long Island Avenue. When completed it will be a wonderful and peaceful place just adjacent to the hustle and bustle of Main Street.

If only it would get completed. At the present time, everyone is waiting for the Town of Southampton to order a second appraisal of the property. The developers rejected an offer based on an earlier appraisal. But now there is a delay. More about this later.

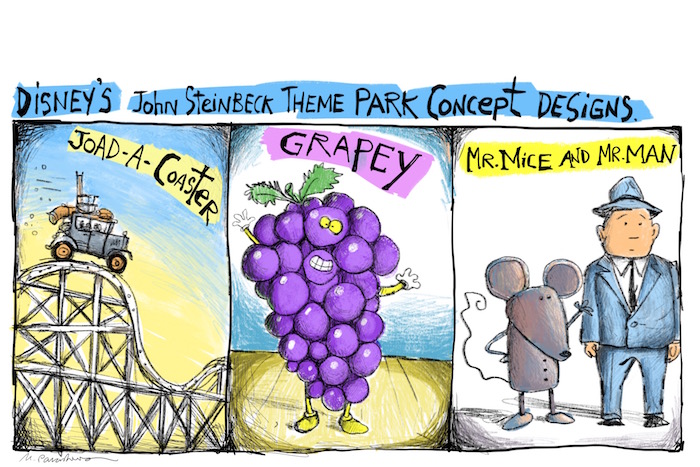

John Steinbeck and his wife Elaine bought a small house on the bay, in 1955. According to Elaine, Steinbeck moved here because it reminded him of the fishing town of Salinas, California. Most of the books he had written up until that time—The Grapes of Wrath, Of Mice and Men and East of Eden—were set in the broken-down community of Salinas or the farm towns around it.

John Steinbeck was 53 when he came to Sag Harbor. Along with Ernest Hemingway, Steinbeck was considered one of the greatest American novelists alive. He’d won the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award, and many of his books had been made into films starring some of the great actors of the age.

Many think that the lingering death of his close friend Ed Ricketts after a car accident led Steinbeck to leave California. Near that same time, his second wife filed for divorce. It was a hard time, and he fell into a deep depression.

John Steinbeck dealt with tragedy by writing. Arriving in Sag Harbor, he built a six-sided work studio on his property. You can see the bay from both the house and the studio today.

It is said that Steinbeck’s abilities as a writer were in decline after East of Eden, and there may be some truth to that. Nevertheless, the novel he wrote while in Sag Harbor, The Winter of Our Discontent, brought him an honor that exceeded all that had come before.

The Secretary of the Nobel Committee, Anders Österling, in awarding Steinbeck their Prize for Literature in 1962, wrote this:

“If at times the critics have seemed to note certain signs of flagging powers, of repetitions that might point to a decrease in vitality, Steinbeck belied their fears most emphatically with The Winter of Our Discontent. Here he attained the same standard which he set in The Grapes of Wrath. Again he holds his position as an independent expounder of the truth with an unbiased instinct for what is genuinely American, be it good or bad.”

In his 30s, Steinbeck had traveled around America talking to poverty stricken men out of work as a result of the Depression. From these experiences came The Grapes of Wrath and Of Mice and Men. He had traveled again as a war correspondent during World War II. Why not, in 1960, get a camper and take off from Sag Harbor with his dog, Charley, and see how things had changed?

Steinbeck found a very different America in the 1960s. He met a lot of interesting characters along the way, and, with Charley as his muse, he wrote about them in Travels with Charley.

The Winter of Our Discontent, typed up in that octagonal office overlooking the bay, was unlike anything he had written before. It was a hard-nosed look at the new reality of “getting ahead” in America, and the kind of cheating that sometimes was done to achieve it.

The main character is a man named Ethan Allen Hawley, who works in a grocery store on Long Island. He has a wife and family and is basically a happy man. But because his parents had been wealthy for a while and then lost it all, his wife expected more of him. He should, by whatever means, make himself rich. He decides on a scheme to take over the successful store where he works. His boss is an illegal immigrant. He calls immigration, and they come to talk to him. At the same time, he commiserates with his boss and persuades him—if he’s going to be taken away—to sell the business to him, cheap. As a result, he’s off and running, a dishonest man involved with stealing, bribery and favoritism, whatever it takes to “get ahead.” In the end, seeing what he has done to himself, he decides to commit suicide. But I won’t give away the ending.

If the Nobel Committee has seen this as a rebirth of the mores and ethics Steinbeck had written about during hte depression—but with changing times—the American critics roundly panned The Winter of Our Discontent as an example of how Steinbeck had lost his way. Steinbeck, confused and saddened, decided he would never write another novel and did not. He died at age 66 in 1968.

Watergate happened four years after his death. Many had second thoughts then about the viability of The Winter of Our Discontent. Perhaps Steinbeck had been right on the money.

Well, Sag Harbor should be congratulated for deciding to name the new park for John Steinbeck. Last year, the developers of the land slated to become a park came to terms with Sag Harbor Village about having the development—a 13-unit condominium—on just about a quarter of the land, with the park on three quarters and the money raised to pay for the park coming from the CPF funds overseen by Southampton Town. An appraisal on the property was then done, but the developers said it left out certain values that might have made it higher. The town should make a new appraisal.

Now, a year later, the order to ask for the second appraisal is not even on the agenda in Southampton Town, although the town, according to attorney Mary Wilson, says that they have a meeting scheduled soon with the developers.

One hopes that this moves along. There have been prior occasions where things have not been moved along. For instance, two years ago a beloved resident of Bridgehampton, Anna Pump, died after being struck by a car at night on Main Street in that hamlet. Clearly inadequate lighting and not clearly enough marked crosswalks played a role.

The money is available for such a fix, but now, two years later, the inadequate lighting remains and the crosswalks still are not clearly marked.

Soon, we are told.